The Laws of Brainjo, Episode 14

Episode 14: The Secret to Playing Faster

It’s a question that comes up with the banjo perhaps more than any other instrument:

“How can I play faster?”

In this edition of the Laws of Brainjo, we’ll be zeroing in on the banjo player’s need for speed, why it’s such a common concern, and the best way to go about getting it.

The answers may surprise you!

More Than Meets The Eye Ear

So just why is it that, for so many aspiring banjoists, speed is such a pressing concern, especially in the world of 3-finger style (though the topic certainly comes up amongst downpickers, too)?

Why is there such an epidemic of speed envy amongst budding banjoists?

Because to the average listener, banjo playing sounds FAST. For many, the very first impression they have upon first hearing a banjo being played is one of speed. The notes are moving by so quickly that it can be difficult to even comprehend what’s going on.

But, as any seasoned 3-finger picker will tell you, much of this is an illusion.

The perception of speed has more to do with the style in which the banjo is played than it does with any superhuman feat of finger flicking.

For one, there’s the 5th string itself. One of the commonalities amongst virtually all styles of 5-string picking is the continued sounding of the 5th string. Without it, we wouldn’t create the droning sound that’s such a signature feature of our beloved ax. But that 5th string drone is an extra sound you don’t hear on most other stringed instruments. That alone gives the impression that something more is going on.

On top of that, there’s also all the extra stuff we banjo players put in between the melody notes. Most styles of 5-string picking involve playing melody notes interspersed with harmonizing banjo sounds, the “decorations” we play around all the notes. In many cases, there’s more decoration than melody.

This is unlike the guitar, where in many cases an arrangement consists of nothing but the melody notes.

If you were to take any banjo arrangement and strip away everything but the melody, it would sound downright tortoise-like in comparison, even without altering the tempo.

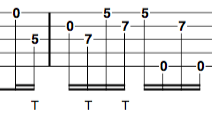

Consider the following example. First, I’m going to play just the melody notes for the song “Grandfather’s Clock” at casual tempo, around 100 BPM:

Now, here I am playing through a 3-finger style version at the same tempo:

As you can hear, all those extra “decorations” give the impression that I’m playing the song faster. I’m playing more notes, yes, but the tempo of the song has not changed.

So, in other words, the 5-string is a BUSY instrument.

And all those extra notes on the banjo futher enhance the illusion that the music on the banjo is being played fast. Which means for you the player, even when sticking to pedestrian tempos, your typical listener will still be left with the impression that you’re tearing it up.

For the beginning banjo player yet to fully grasp the nuances of the style, it can be tempting to conclude that the reason your playing doesn’t sound quite just right yet is because it’s just not fast enough.

But this is almost NEVER the case.

Now that I’ve hopefully thrown a splash of cold water on your lust for speed, let’s now examine the issue at hand: just how does one develop the ability to play faster?

To answer it, we naturally need to first talk about dental hygiene.

Bristling with Speed

I’m sure the vast majority of you reading this are well accustomed to the act of brushing your teeth [insert requisite British joke here]. In all likelihood, it’s something you’ve been doing most of your life [expound further on the joke here if desired].

Yet, you didn’t always know how to do it.

Brushing your teeth is a learned behavior with a specific and stereotyped set of movements that unfold in predictable sequence from start to finish. The whole thing seems trivial to you now I’m sure, but if you’ve watched a young child learning it all for the first time, you’ll note there’s a bit more to it than you may now appreciate.

You grab the tube of paste, unscrew the cap, turn the faucet on (cold side) to wet the bristles, turn it off, align the tube with the brush, squeeze a set amount onto the brush, and so on. There’s actually quite a bit going on!

For a young child who has yet to master it, it’s quite a bit to remember and master.

Now, imagine I were to ask you tonight to brush your teeth twice as fast as usual. Could you do it?

Sure, you might feel a bit stressed, and your dentist would surely protest, but nonetheless I imagine you could still ramp up the speed of the whole affair with little effort.

But what about the young child who still hasn’t learned it all? What would happen if we asked him or her to double their speed? A faster performance?

Unlikely!

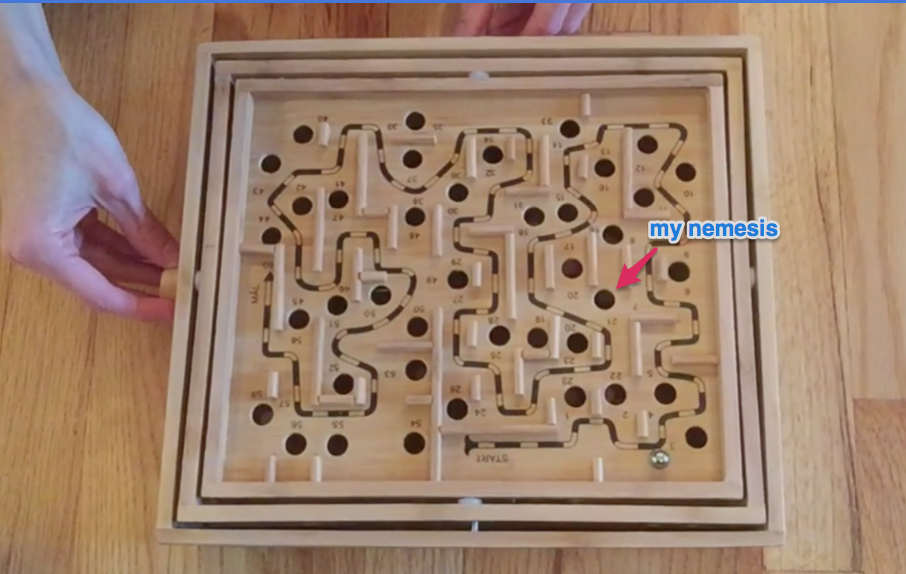

In the child’s case, each step in the act still requires conscious deliberation, and trying to speed that up would, if anything, likely have the opposite result. More than likely, it would just increase their error rate (sound familiar?), resulting in an overall LONGER time to complete the task correctly.

The reason you can increase your speed easily and the young child can’t is because you’ve fully learned the entire behavior – learned it to the point where it requires no conscious thought, where you can move through the whole sequence while your conscious mind is entirely engaged otherwise. For the child, on the other hand, each step still demands their full attention.

In learning parlance, the adult has moved from the beginning state of conscious uncompetence (“I can’t do it AND I must concentrate hard when I try”) to unconscious competence (“I can do it all with my conscious attention focused elsewhere”).

In the brain, the neural networks that control these behaviors (formed through the learning process) have become compact and efficient, and are now fully housed in neurons that exist beneath the cortical layer (“subcortical“).

And it’s this shift into the final stage of learning, and the attendant changes in neurobiology that supported it, that allowed you to increase your speed at will. As a result, you can double your speed, even though you never once worked directly on fast teeth brushing.

Being able to brush your teeth faster was a natural byproduct of the learning the skill well. It happened as a result of working on other things, not by working on it directly.

So, then, what would be the best advice for the young child looking to improve their own teeth brushing speed?

Playing Slow to Play Fast

With its teeth brushing or banjo picking, the advice is the same.

The ability to play fast happens as a natural byproduct of the learning process, or learning the mechanics of banjo picking so that you can play automatically, without thinking about it. Once you’ve reached this stage, speed comes naturally (for more on the concept of automaticity, and how to test for it, check out Episode 2).

This concept is also embedded in the mantra you’ll hear repeated in music conservatories: “the secret to playing fast is playing slow.” Work on proper mechanics and timing at the speeds that allow for it, preferably with an external timekeeping device, and ultimately increasing speed is trivial.

Brainjo Law #16: Speed develops as a natural byproduct of a solid learning process.

Before I go, I’d like to put one more dagger in heart of the banjoist’s need for speed – a final plea in the service of banjo public relations.

If you happen to find yourself pining for a few extra BPMs, please remember that playing a song faster does not make it better. In fact, playing it faster in many cases will make it worse.

And playing fast for the sake of playing fast always sounds worse.

So banish all egocentric motives for speed. Choose the tempo that allows you to best showcase the song you’re playing. Play to entertain, not to impress.

Let go of your need for speed, and speed will find you.

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents