About the Laws of Brainjo Series

Written in partnership with the Banjo Hangout, the “Immutable Laws of Brainjo” is a monthly series on how to apply the science of learning and neuroplasticity to practice banjo more effectively – these are also the principles that serve as the foundation for the Brainjo Method for music instruction.

(RELATED: The Brainjo Method forms the basis for the Breakthrough Banjo course. Click here to learn more about the course.)

I recently had the pleasure of attending “The Big Crafty” arts and crafts fair at the US Cellular Center in Asheville, North Carolina.

It’s an inspiring place to browse (and Asheville an inspiring place to be), with makers of all types displaying their wares of inspiring originality and artistry.

As I was walking from one booth to the next, I found myself reflecting on how different the experience was here from that of browsing the housewares section of your local department store, where you might find similar kinds of items on display.

In the department store, perfection is the norm, the product of factory-made precision. Perfection is required, and expected. Anything less than perfect is either discarded or banished to the land of misfit wares, aka the discount section. In the housewares section, there’s a zero tolerance policy for flaws.

At the craft fair, on the other hand, the pieces are far from perfect – at least in the absolute, geometrical sense. The shapes are irregular, the colors outside the margins, the round parts asymmetrical.

All of it clearly not the work of machines, but of human hands.

And all of it beautiful. Here, imperfections aren’t just tolerated, they’re celebrated. Imperfections are a feature, not a bug.

So what do I prefer?

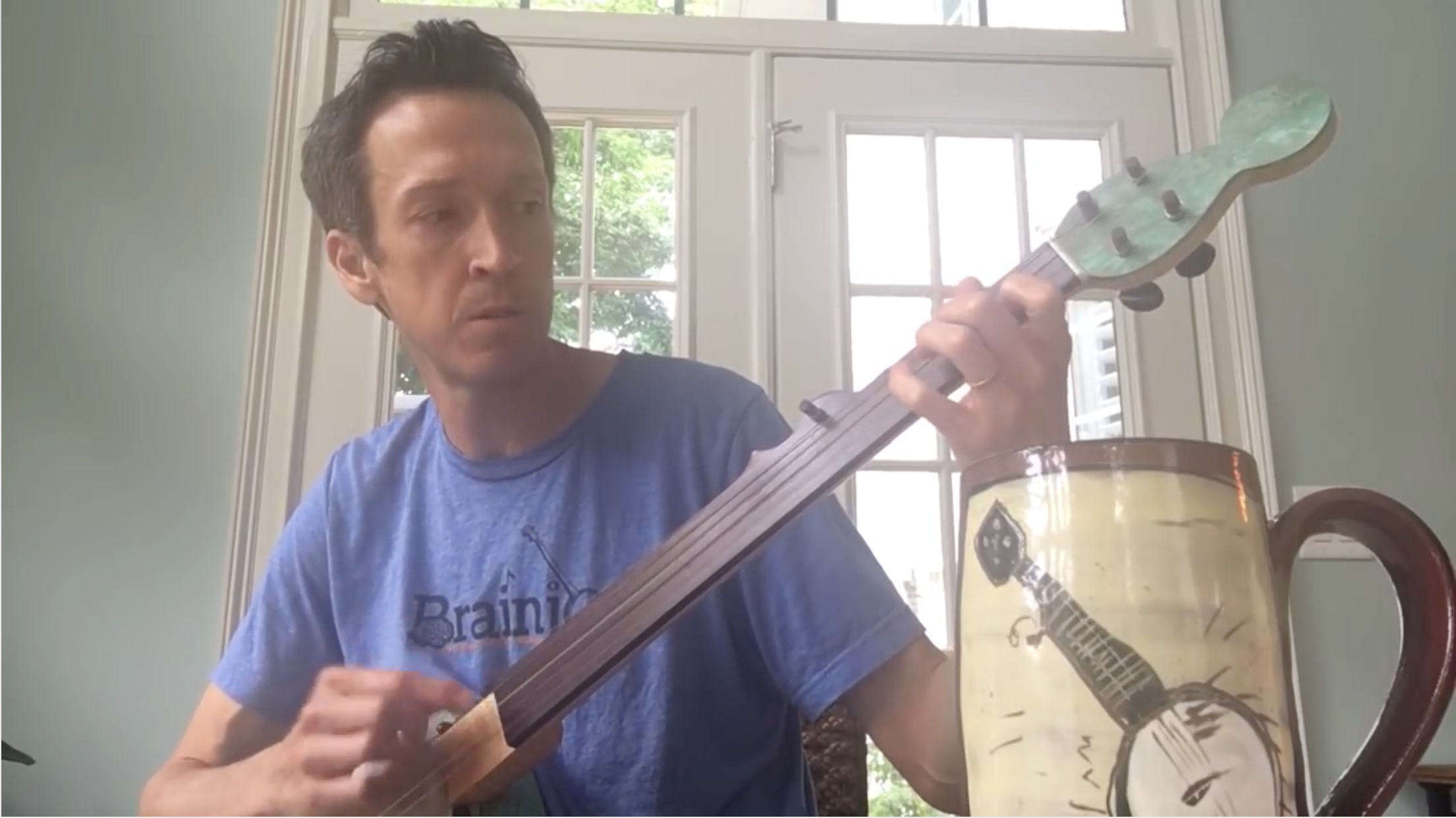

I’ll answer that question with a picture of my favorite coffee mug, the one I drink my first cup of coffee from every morning (which was featured in a video of “Feast Here Tonight“):

Yes, I have a cupboard full of perfectly made, store-bought mugs of various sorts. None hold the same appeal.

(RELATED: The mug is made by Tyson Graham of Polk County, NC. You can click here to grab one of your own!)

Finding Wabi-Sabi

Not long ago, I learned that the Japanese have a name for this aesthetic: wabi-sabi. Besides being ridiculously fun to say, wabi-sabi has also since become one of my favorite concepts (not to be confused with wasabi, which is equally fun to say, but goes better with sushi).

According to aesthetics expert Leonard Koren, it is a characteristic essential to the concept of beauty in Japan, occupying “roughly the same position in the Japanese pantheon of aesthetic values as do the Greek ideals of beauty and perfection in the far West.“

“Wabi-sabi nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.“

While those of us in the West may be more preoccupied with perfection, we too have an appreciation and names for this aesthetic. Rustic simplicity. Understated elegance.

Perhaps the most fundamental characteristic of wabi-sabi is that it bears the unmistakable signs of human hands. Signs that convey to us that what we’re beholding was made by one person, for another.

Signs that are missing from machine-made perfection.

So what’s the connection here to music-making?

I think it’s pretty safe to say that all of us at one point or another have battled with the siren song of perfectionism. Of a desire to make what we play come out perfect.

Judging your playing against some imagined ideal can be especially troublesome when you’re first starting out, when the gap between where you are and that beguiling perfect version is as wide as it’ll ever be.

But the battle never really ends. I’d venture that the quest for perfection is the ultimate source of all dissatisfaction throughout anyone’s musical journey.

Yet, here is the irony revealed by wabi-sabi: even if we were to attain that perfect ideal, odds are we wouldn’t even like what we heard.

Perfect music, like perfect pottery, perfect coffee tables, or perfect frying pans, leaves us wanting. Why? Because it lacks the human element.

Because perfect music lacks….wabi-sabi.

Regardless of the form in which it comes, our experience of art is elevated when we can feel that it’s been crafted by human hands. When it’s clear that someone else made it for us to enjoy.

It’s easy to lose sight of this basic fact about music – that it is something that connects us. That it is stuff we make for each other.

It’s easy to get so focused on the details that we forget what drew us to playing music in the first place.

The point here is not to encourage you (or me!) to drop all concern for quality. It’s to remember that there’s so much more to music-making than getting every note right. That there’s so much more to the experience of music than just hearing all the “right” notes in all the “right” places.

Furthermore, imperfection may even be necessary. Nothing, including perfection, comes without trade-offs. In other words, to achieve technical perfection, were that even possible, we’d likely have to sacrifice something else.

Grandpa Jones may not have been the most technically precise banjo picker. Nor would he have wanted to be, as that extra bit of precision would have come at the expense of the raucous, hard-driving sound that he wanted to make. The very sound that fans love him for.

We don’t listen to our favorite musicians because they are perfect. We listen because they move us.

Progress and Connection over Perfection

One remarkable thing I’ve noticed over the years is that I enjoy hearing just about anyone play the banjo, regardless of whether they’ve been playing for 5 weeks or 50 years. Why is that? Because technical precision is not required to make a connection.

Again, it’s easy to think that if your playing isn’t up to a certain level, then it’s not worthy of presenting to other ears.

But that view ignores the human element. That view comes from a conception of music narrowed by the artifice of modern musical conventions. That view misses the beauty of wabi-sabi.

When we humans began making music hundreds of thousands of years ago, it wasn’t to make it to Carnegie Hall. It wasn’t to win contests. It wasn’t so we could score a record deal.

It was to connect with each other. It was to celebrate how lucky we are to be spending a little precious time in this incredible universe surrounded by people we love.

So may you all have a phenomenal 2020, and fill your bellies with wabi-sabi.

9 Ways to Practice Smarter – free book and video

The “9 Ways to Practice Smarter” is a collection of 9 essential ways to get more out of your banjo practice. Click the button below to download the book, along with access to the full video.

To learn more about the Breakthrough Banjo courses for clawhammer and fingerstyle banjo, click the relevant link below:

— Breakthrough Banjo for CLAWHAMMER Banjo —

— Breakthrough Banjo for FINGERSTYLE Banjo —

— The Laws of Brainjo Table of Contents —

View the Brainjo Course Catalog