Episode 21: How to Break the Tab Habit

In aural traditions (like the banjo), the pinnacle of musicianship, regardless of chosen instrument, is musical fluency, which I’ve defined previously as the ability to take imagined sounds and, via the movement of the hands, get them out into the world and into the ears of others.

The analog here is linguistic fluency, defined as the ability to take imagined concepts and, via the movement of the vocal cords, get them out into the world and into the ears of others. It’s the transfer of information, and all its attendant meaning, from one mind to another.

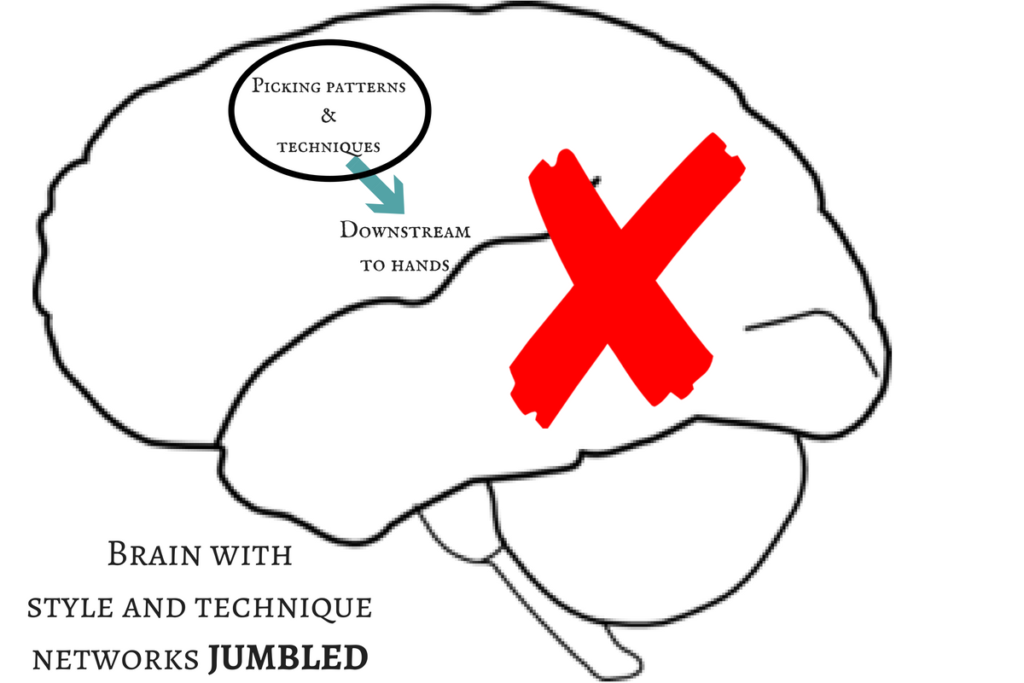

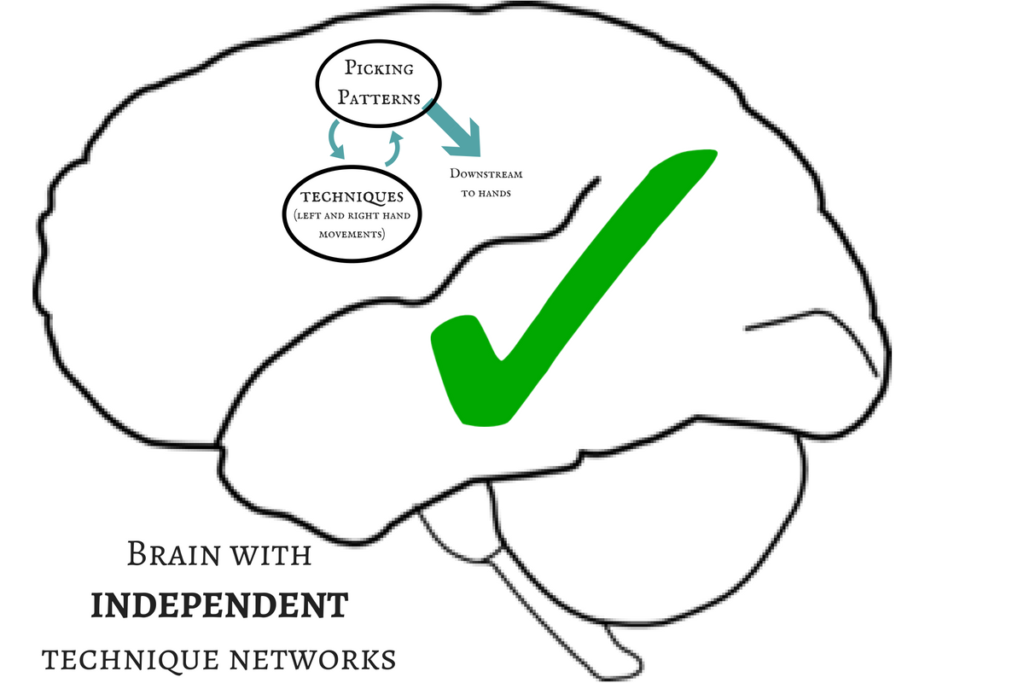

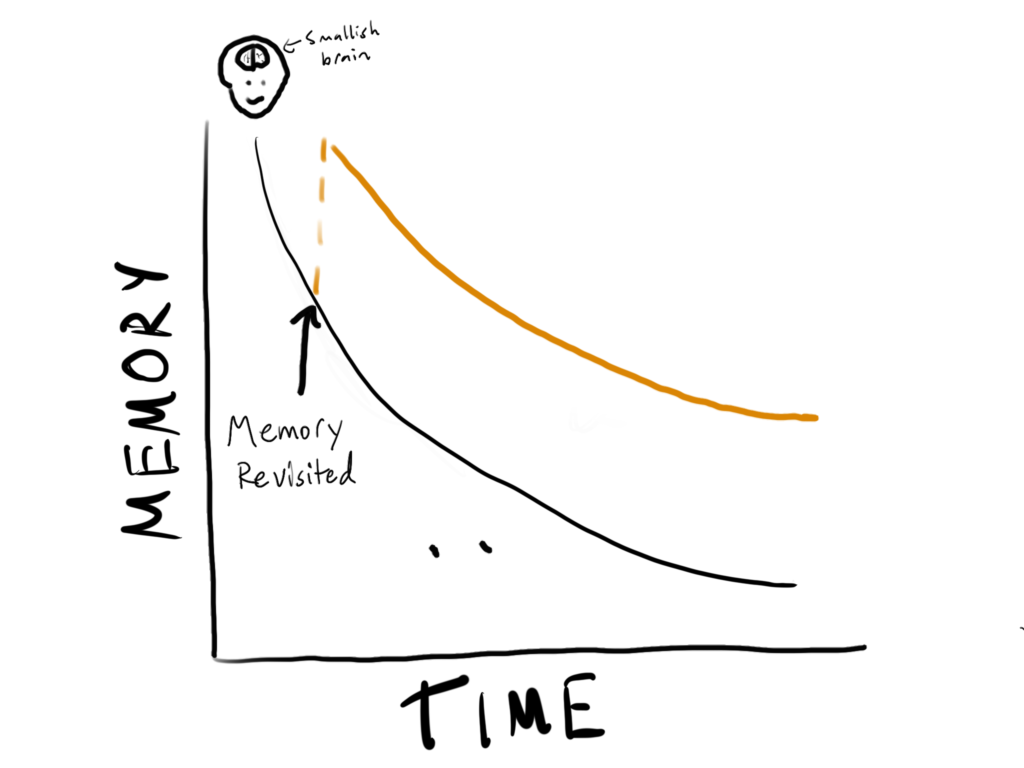

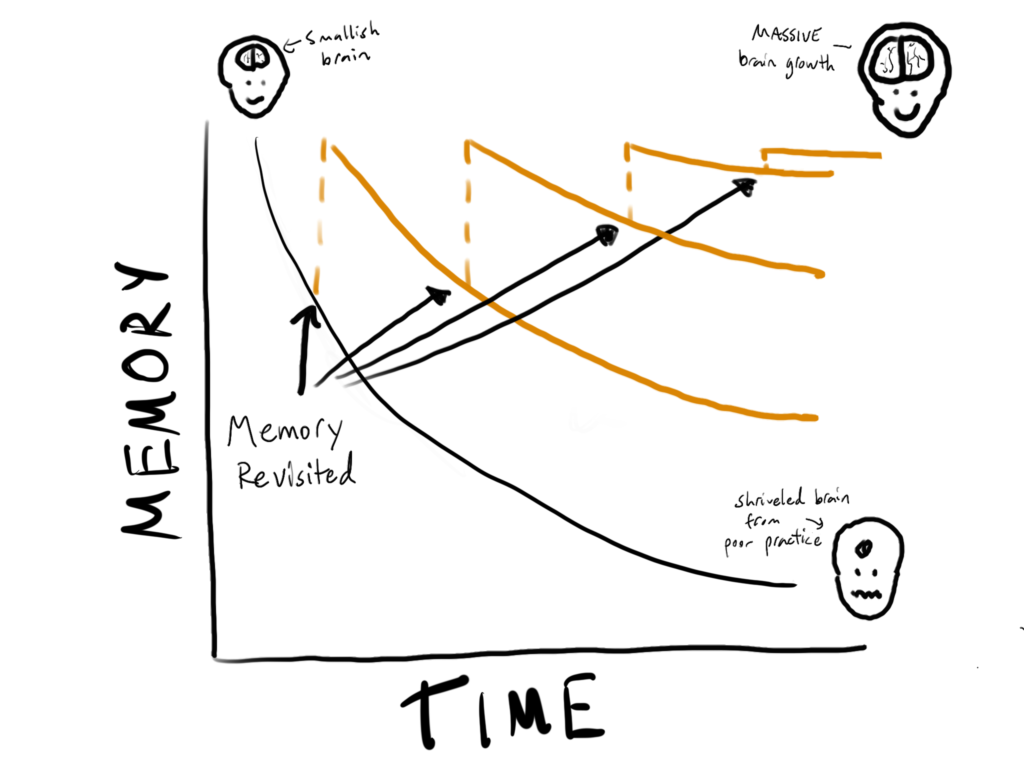

The ability to do such a thing requires a specific type of neural machinery, which we build through practice. Specifically, it requires that we build mappings in the brain between the sounds we imagine and the instrument-specific movements of the hands needed to make them.

And, as you’ll note, written notation isn’t part of the machinery needed for musical fluency. Which means that our goal, if we wish to develop this ability, is to ensure that written notation (in this case banjo tab) isn’t baked into our core banjo playing circuitry (note: this does NOT mean that tabs aren’t a useful tool in the learning process – on the contrary, they are extremely useful when used wisely).

The easiest way to avoid such a situation of tab dependency, where written notation is baked into our banjo playing networks, is to take great care in the creation of said machinery, paying careful attention to the sequence and structure of practice.

[RELATED: The 4-part course on Learning To Play By Ear is now part of Breakthrough Banjo. Click here to learn more, and for a video tour inside.]Alas, this all too often does not happen. So, what to do if you find yourself in this predicament? Perhaps you’ve been playing a for a while, be it for months or even years, and you find the idea of playing by ear hopeless, unable at this point to even envision a tab-free path to banjo playing. Is it a truly hopeless situation?

Not in the least. The upside here is that tab dependency is not indicative of some inherent flaw in your own capacity to make music by ear, but instead a natural biological consequence of the manner in which you went about learning. Barring true tone deafness, anyone – yes, anyone – can play music entirely by ear, provided they follow the a learning path that leads to that destination.

First, let’s review some of the signs of tab dependency:

- You find it difficult to “memorize” a new tune (“memorizing” tunes is FAR more challenging when they’re learned exclusively by notation).

- When you learn a new tune, something feels like it’s missing. Even though all the notes are there, it doesn’t sound like the version you were trying to learn.

- You find it very difficult to make changes in the way you play a tune once it’s learned.

- You find playing a tune along with others, or jamming, very challenging.

- You have a difficult time picking out the chord progression for a new tune.

So if some of these things resonate with you, and you’d like to free yourself of the tab shackles, then let’s discuss how to right the ship.

Breaking the Habit

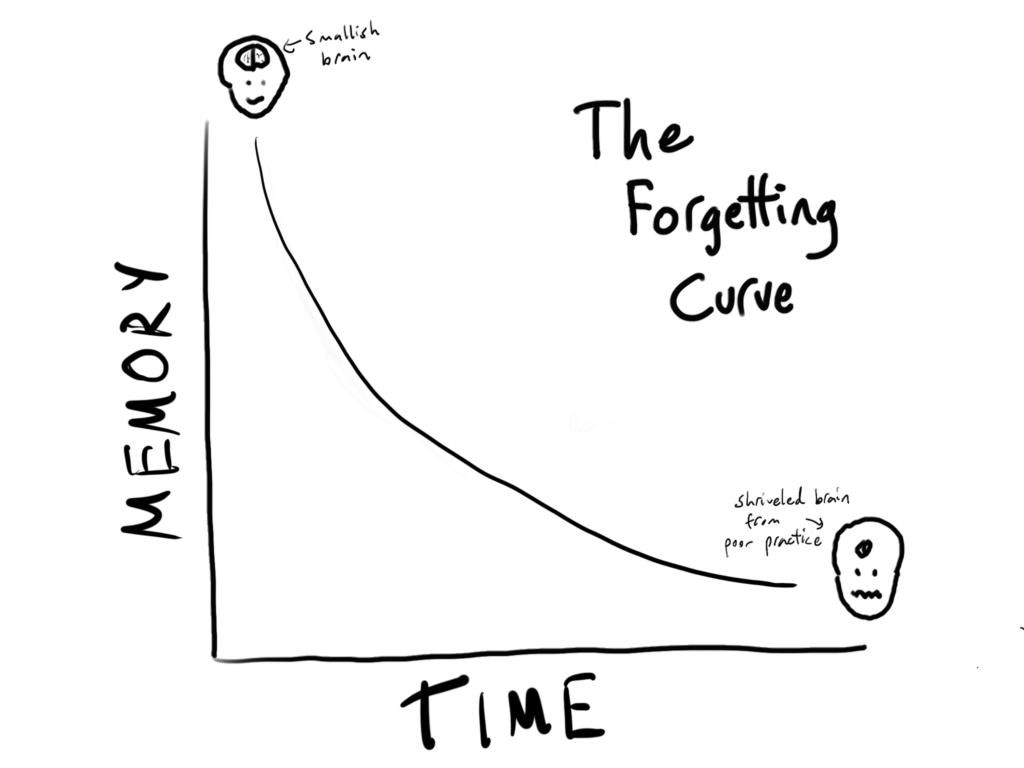

First, the bad news. Breaking the tab habit, as is the case with all habit breaking, requires the formation of NEW habits. Better habits to replace the old ones.

This means having to take a few steps back in order to move forwards again, like a veteran golfer with a 30 handicap and a swing full of compensations and compromises with no hope of shredding a point off his score without going back to basics to build his swing back from the ground up. It’s not in our nature to do such things.

But it’s an essential thing to do IF you wish to progress.

So, here are a few exercises to help you get started clearing new tab-free trails inside your noggin’.

EXERCISE #1: Spend lots of time singing and humming.

When playing a tune, be it for the first or hundredth time, always begin with a “music first” approach. In other words, make sure before you set about to play the tune on your instrument that you first know the music you want to be making. And knowing means being able to sing or hum what it is you wish to play.

The reason this is so important is because, with written notation, it’s entirely possible to learn new tunes simply by memorizing the movements required to play them. By memorizing the movements, you could theoretically learn from tab without ever involving your ears in the process. But this would be precisely the opposite thing we wish to do.

So spend plenty of time either singing or humming the music you play, or one day would like to play, on your banjo. Your goal here is not to become a great singer, but rather to build up a robust musical imagination.

EXERCISE #2: Practice Visualizing.

Visualization is one of my favorite techniques for developing ear skills. Take a tune you already know or are in the process of learning, and visualize yourself playing it (first person perspective), and hearing the result in your mind.

If you initially struggle with this, then try method #4 below as a bridge to getting here. You also may find it easier in the beginning to start with short phrases of the tune, two to four measures perhaps (for example, you can even start doing this with your banjo nearby. Play a few measures on the banjo, put the banjo aside, and then visualize yourself playing those same measures while hearing the result in your mind).

Do this enough, and you may find that your start doing this sort of thing automatically when you’re away from your banjo (while stuck in traffic, engaged in boring conversation, etc.).

EXERCISE #3: Start picking out simple melodies by ear.

The fundamental skill for playing by ear is simply the ability to match a sound in your mind with a sound on your banjo. Unless you are tone deaf, you are capable of doing this, with practice (click here to take the ear test and find out whether or not you have what it takes to learn to play by ear).

If you’ve never done this sort of thing, just start with some simple melodies that you know very well, and work on finding the basic melody on the banjo.

(RELATED: Click here to take a mini-course on “Getting Started Playing By Ear”)

EXERCISE #4: When you do learn new tunes from tab, use the Brainjo tune-learnin‘ system to do so. Then combine it with visualization practice.

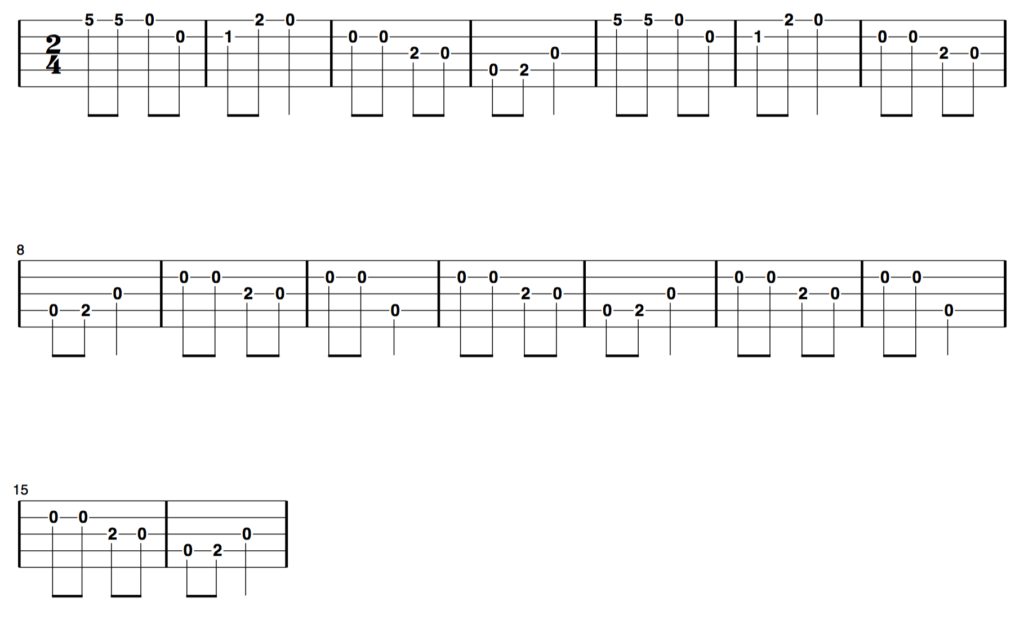

Step 1: Learn a new tune via the Brainjo tune learnin‘ system, a method of learning from tab to minimize the risk of tab dependency. Click here to learn more about it.

Step 2: Once you’ve learned the tune, record yourself playing it. The speed at which you play it here is entirely unimportant, so play it is slow as need be to play it well.

Step 3: Play the recording, and while doing so visualize yourself playing it (you may find that you do this naturally, as you already have a memory of the recording experience to draw from).

Step 4: Continue this listening and visualizing routine as much as you’d like, but periodically try to visualize yourself playing through the entire tune without the recording. Once you’re able to play the entire tune start to finish without the recording, continue to practice visualizing it in this manner (as in Exercise #2).

I should note here that it’s probably best to start applying these exercises to NEW tunes, rather than ones you’ve already learned from tab. When trying to do this with previously learned tunes, your brain will find it all too easy to go down the well-worn tab dependent pathways, so you’ll be fighting against an old habit while simultaneously trying to build a new one. Not easy.

As said in the beginning, the ability to play music independent of notation requires that we create neural networks that do just that. Networks that can translate the music in our mind to the movement of our hands (rather than the symbols we see to the movements of the hands).

Get started with the exercises above, and you’ll start doing just that – building new, tab-independent banjo playing neural networks that will ultimately allow you to break the tab habit.

— The Laws of Brainjo Table of Contents —