The Laws of Brainjo, Episode 12

Is It Safe To Use Tab?

I was awoken, as I was well accustomed to, by the dreaded sound of my pager.

The year was 2004. The time…2:30 AM. I was the on call neurologist for two hospitals.

“Hey Dr. T, I’ve got a really interesting case for you,” said the voice on the line.

Nothing is interesting at 2:30 AM, I thought, except my pillow.

I was speaking with the nightshift doctor in the Malcolm Randall VA ER, and he was clearly better adapted to middle-of-the-night conversation than I. “Can I just run this case by you, I’m not sure what to make of it. It’s probably nothing.”

“Sure, what’s up?”

“Well, he says he can’t read. He tried to pick up a book tonight and couldn’t read any of it. But here’s the strange thing, his vision is perfectly fine. And he has no problems talking, no slurred speech or anything. You ever heard of anything like this?”

“It just started tonight?” I asked.

“Yep.”

“I’ll be right there.”

My examination indeed confirmed what the ER physician had reported. The patient, G.R. (as we’ll refer to him), was having trouble reading (more specifically in applying the rules of phonology). But, as the ER doc said, his vision was otherwise fine, as was his speech.

I knew this was bad.

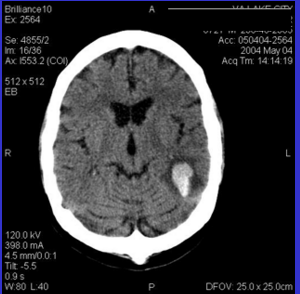

This was the CT scan of his head:

That bright blob on the lower right hand side of the image, surrounded by a dark rim, is blood. G.R. had bled inside his brain, at the juncture between the occipital and parietal lobes in the left hemisphere, a place where symbolic visual information is decoded. Things like written words on a page, for example.

Despite our technological advances, cases like these still form the backbone of our understanding of human cognition. The specific ways in which brain function degrades when certain parts are taken offline offers us a unique and powerful window into how the brain is organized, and how it processes information.

This includes much of what we know about our gifts for communication, including speech, reading, and writing – information we can use to our advantage as we try to build a banjo playing brain.

Information that can even help us to answer the question of whether tab has a place in the learning process.

More on G.R. in a bit.

The Origins of Written Music

I think it’s safe to say that, just as we humans were talking long before we were writing, humans were playing music long before we started recording that music in written form. Which means that, for most of human history, music was purely an aural tradition, passed along from one person to another solely by ear. Humans are quite capable of learning music without any written notation whatsoever.

And when we finally did decide to create a written system of musical notation (roughly 2,000 years ago we believe), its primary purpose was for the preservation and dissemination of music. Up until that point, music only existed in the human mind. Notation was the only way musical information could be stored outside of the human mind, as recorded media (i.e. the Edison phonograph) didn’t develop until a few thousand years later.

Just as writing was developed as a way of storing and disseminating knowledge and information for later retrieval, musical notation was likely created to perform a similar function (rather than as a system for teaching).

Later on, when composers needed a way to coordinate large numbers of musicians in a symphony orchestra, they turned to written music to do the job. And so if you were a musician with your sights set on playing in said orchestra some day, then you’d better learn to read that written music yourself.

But somewhere along the way, perhaps because we were able to record music in writing long before we could record the actual music, learning by reading music became the accepted way music was taught. In the days before records, tapes, CDs, and iTunes, the only way to easily disseminate a tune to thousands of ears was to WRITE IT DOWN.

Times, of course, have changed.

We no longer need to write music down in notation form to store it. Furthermore, as a means of transmitting musical information, it is an inferior tool for doing so when we now almost always have access to the REAL thing. Written notation for a piece of music is a representation of the thing, while a recording of a piece of music is the thing.

The Potential Perils of Tab

Those of you who’ve followed along in this series know that we attain new skills through the creation of skill-specific neural networks in the brain, and those networks are built through practice. We have the ability to mold our brains to our own specifications.

While this remarkable feature holds great promise and potential, it also means we must take care in ensuring the networks we create actually do the thing we want.

Let’s consider an example.

John has just bought his first banjo after having dreamed of playing it for many years. He’s motivated and ready to learn, and sets a goal of playing in his first jam in 6 months.

He gets down the basic techniques of banjo playing, and then sets about to start learning some tunes. He finds a book of tablature, and gets to work, putting a couple of hours of practice in every day.

Several months go by and John is making serious progress. He can play about 20 tunes up to speed, though still has trouble playing through a tune without the tab in front of him.

His wife, once dismissive of his newfound interest, remarks that he’s sounding pretty good. Buoyed by her encouragement, he decides it’s time to venture to his first jam.

Disaster strikes.

Within a few minutes, John realizes that he’s in way over his head. Even when tunes he knows comes up, he can’t keep up, and can’t muster to play anything that sounds remotely like music.

He leaves dejected and demoralized. The banjo is retired to the closet, where it remains collecting dust for the next decade.

Building It Right

In prior episodes, we’ve reviewed the type of neural networks that support the playing of a master banjoist: networks that efficiently translate musical ideas into a motor plan for moving the limbs (so that those musical ideas are emitted as banjo sounds). We may refer to these as “sound-to-motor” networks.

Banjo playing networks built exclusively through the use of written music, on the other hand, operate quite differently. These networks translate visual information into movement of the limbs (so that the written code is translated into banjo sounds). We may refer to these as “print-to-motor” networks.

So, the “print-to-motor” neural network that John has diligently built over many months relies upon tab for its operation. What’s more, no neural routes to playing independent of tab exist in John’s brain, making it biologically impossible for him to succeed in a jam!

John didn’t fail because he’s a bad musician, he failed because he built neural networks that weren’t in line with his goals.

Revisiting G.R.

G.R., the patient with the brain hemorrhage that rendered him dyslexic, couldn’t read because the hemorrhage destroyed the neural networks that convert the printed word into movement of the vocal chords.

As stated earlier, cases like G.R. reveal the functional organization of the human brain, in this instance showing us that there are segregated language networks of various types, each with its specific function, each created through a specific kind of practice. G.R., like most of us, could speak fluently long before he ever attempted to decode his first written word. Before reading instruction ever began, he already had neural networks that could transform mental concepts into movements of the vocal chords.

And it was only when that reading instruction began that he started forming the “print-to-motor” networks that could translate markings on a page into movements of the vocal chords.

This segregation of function explains why he could suffer a stroke that obliterated one linguistic skill (his capacity to read) but left another (his ability to translate thoughts into speech) intact.

So what exactly does this type of knowledge tell us about the role of written music in the learning process? It tells us that if we wish to create “sound-to-motor” networks like the master players, then we should avoid incorporating musical notation into our banjo playing networks.

It tells us that we want to build banjo playing neural networks that operate independently of tab.

Are We Tabbed Out?

So if we don’t want tab incorporated into our banjo playing networks, does this mean we need to abandon it altogether? Does tab have any place in the learning process at all? Is there a way to use it responsibly?

No. Yes. Yes.

While our ultimate goal may be to build networks that can translate musical ideas into motor programs of the limbs independent of printed music, I think it’s entirely possible to use tab as an aid in that process.

Most importantly, tab can be an invaluable learning tool, ideally suited for conveying certain kinds of information.

Years ago, after hearing several of his tunes performed by a guitarist at a local farmer’s market, I became enamored with country blues guitarist Mississippi John Hurt. After that performance, I soon built up a library of Hurt’s music, and set about to learn some of his material.

I soon found that things weren’t as simple as they seemed, and I struggled at first to figure out exactly how we was getting those sounds out his guitar. Then one day I stumbled across a tab for one of his tunes (“Stagger Lee”), and there lied the keys to the kingdom.

Just seeing that one tab was all it took to unlock the mystery of his style. In a matter of minutes, my eyes were able to unlock a pattern that my ears could not, even after hours and hours of listening. The result was a giant leap forward in my learning process.

Tab in and of itself is neither good nor bad. It’s only in the way in which it’s used that determines whether it hurts or helps. I use tab a good bit in the Brainjo teaching materials, but the Brainjo Method itself is designed so that the student develops banjo playing neural networks that are independent of it.

So there’s absolutely no reason to abandon tab altogether, provided you are mindful of the way in which you use it, and practice in ways that promote the creation of “sound-to-motor” networks that exist independently of it. Here are some strategies for ensuring that you do so:

- When learning a tune from tab, get your eyes off of it as soon as possible. Read more my recommended approach to learning tunes from tab in the Brainjo Tune Learnin’ System.

- After you’ve learned a tune, visualize yourself playing through it while away from your banjo. Read more about visualization here.

- Listen, listen, listen to lots of music. As your skills grow, imagine yourself playing along while listening. What would you play? How would you play it?

- Pick out tunes by ear. Start simple and build this skill. Start with picking out simple melodies (just the basic melody itself, not a banjo player’s arrangement of it). Then start working on creating your own arrangements from that melody. You can learn more about how to do this here.

- Practice jamming (without any written music). Attend a local jam, or just practice along with recorded tracks.

BRAINJO LAW#14: Musical notation (including tab), when used wisely, can be a helpful aid in the learning process, provided that you practice in ways that doesn’t incorporate it into banjo playing networks.

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents