BANJO BREAKTHROUGH: Jay Whitehair

“Scary Progress”

On Breaking Out of the Rut

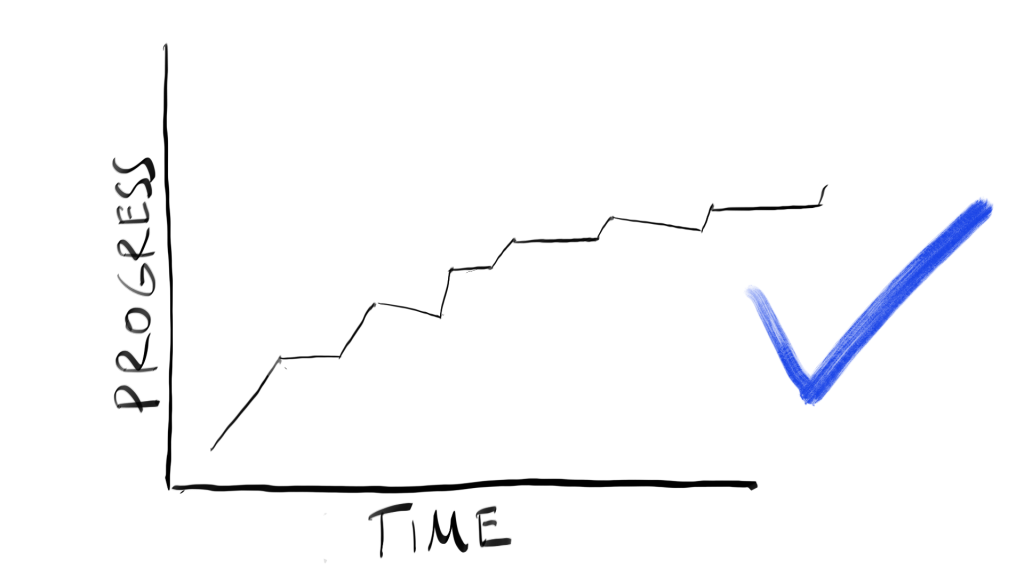

58 year old Jay Whitehair first picked up a banjo roughly 35 years ago, but it had lay dormant most of that time. As is so often the case, Jay would pick it up for a bit and then reach a plateau that he found it difficult to push through:

Having already had a fair amount of playing experience at the start of the course, Jay learned how important a rock solid foundation is to future progress:

Jay On Finally Playing With Others

At the start of the course, Jay set the goal of playing in front of others in one year. Just a few months later, he’d conquered that goal…and then some.

After 35 years of fits and starts with the banjo, it would have been all to easy for Jay to conclude that he just didn’t have what it took to break free from the rut he often found himself in. But, thanks to his persistence and the right learning path, he’s now doing things he still finds hard to believe.

When asked of his favorite thing about Breakthrough Banjo, Jay replies:

It’s never too late.

Kudos to Jay for making his Breakaway.

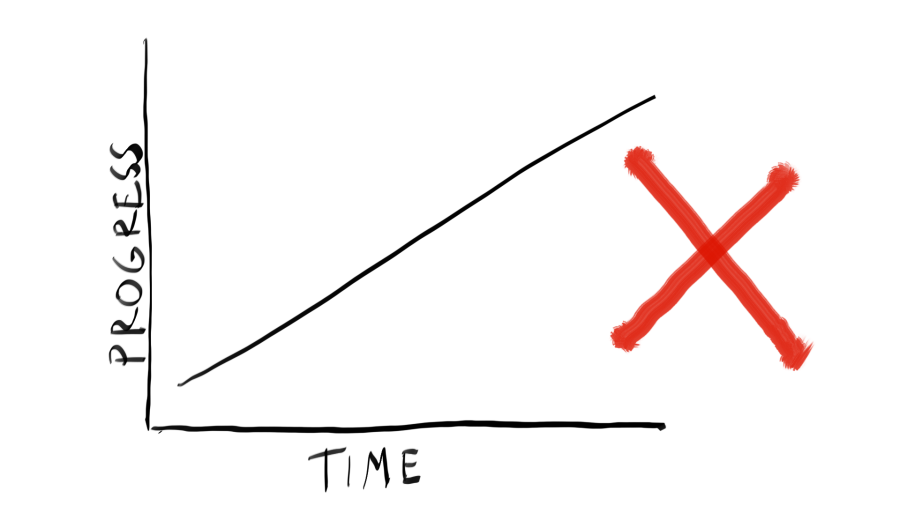

I’ll bet this has happened to you:

I’ll bet this has happened to you: