The Laws of Brainjo, Episode 9

The Meaning of Mastery

Adam Hurt – Tradition Bearer or Innovator?

I recently launched the first installment in the Masters of Clawhammer, a series in which we dissect and analyze the story and style of a master player. For the inaugural episode, I was joined by master banjoist Adam Hurt.

Producing the course was a thought provoking experience in many ways, and a topic that I’ve continued to dwell on since the project began has been the notion of mastery itself.

Given that this “Laws of Brainjo” series on the art and science of effective practice is all about how to carve a path to mastery, and given that I just launched a series all about banjo masters, I thought it may be time to address the concept head on!

Which brings me to the question of the day:

Just what exactly does it mean to be a master of banjo?

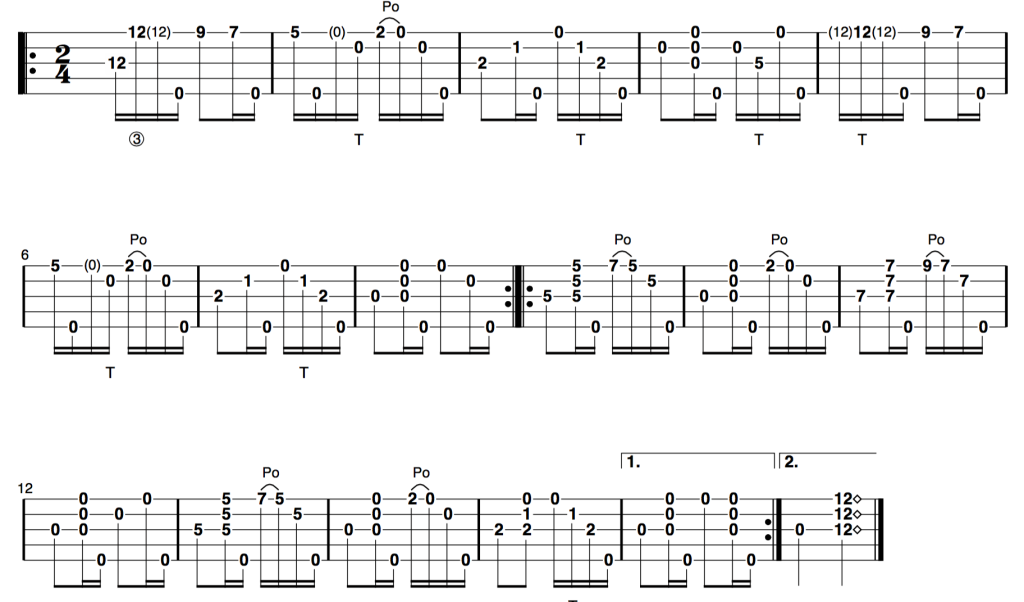

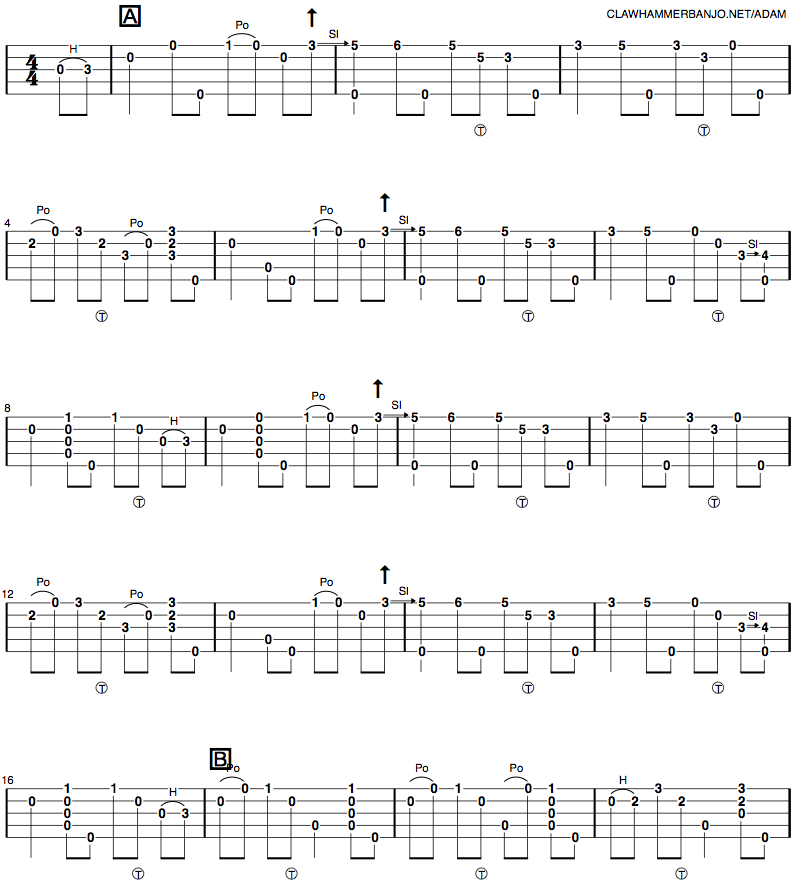

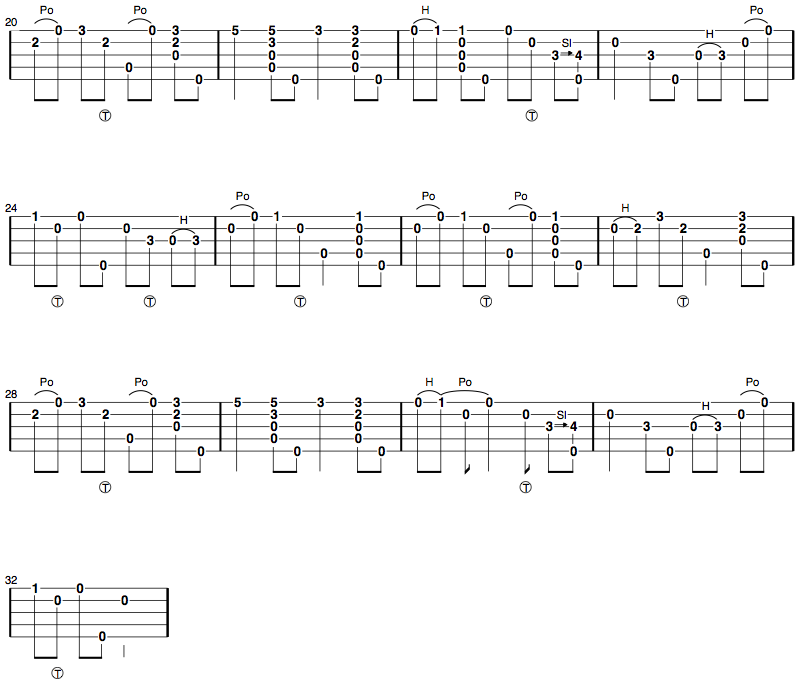

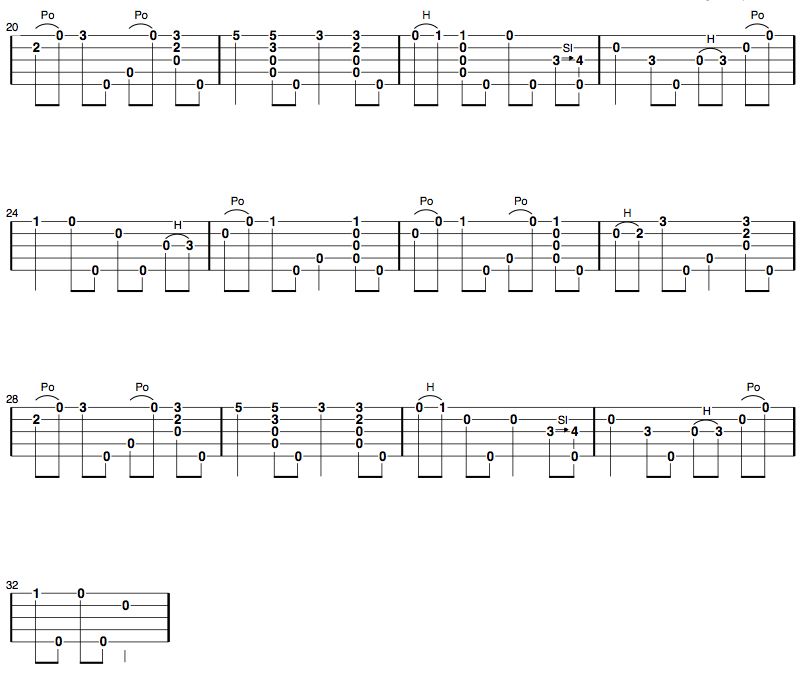

To start this discussion, take a listen to this tune by Adam, one of ten he played as part of the concert:

I think you’ll agree that this tune is gorgeously played and arranged.

And I think you’ll also agree that this isn’t your great grandfather’s clawhammer. Had someone played this recording while you were blindfolded, I doubt you’d guess that it was a mid-20th century field recording snagged in the foothills of North Carolina.

Many would describe Adam’s playing as “innovative”, that his approach is one that pushes the boundaries of clawhammer banjo.

So it may surprise you to learn that, as Adam reveals in the interview, he is very much a student of tradition. Here’s Adam’s in his own words:

“What I think I do different from a lot of people in the melodic clawhammer banjo camp is I use more traditional banjo techniques to create the melodic turns of phrase that I want.“

Adam is often lumped into the “melodic” camp of banjo players (“melodic” meaning he likes to play as many notes from the fiddle as possible), which most folks would consider to be a more “modern” approach to clawhammer. And his playing clearly fits the bill.

Yet, his style has always been uniquely identifiable amongst other melodic players. A few notes into any tune leaves no doubt it’s him.

Yes, this is due in part to an almost inhuman precision of tone and technique. But there had always been something else different about it that previously I couldn’t quite put my finger on.

Now I realize what that was, which is the deliberate, thoughtful, and….innovative use of traditional 5-string banjo techniques in the service of a melodic approach. This is the thing that made his playing stand out most from the melodic crowd.

Lessons From Banjo Camp

Back in 2005, back when I was first getting into clawhammer banjo, I attended Suwannee Old-Time Banjo Camp in North Florida. It was an incredible experience in so many ways, and in retrospect a real inflection point in my life.

If you’ve never been to a banjo camp before, I highly recommend it. There’s something special that happens when people get to geek out in the woods for days around a common interest. Especially when there are banjos involved.

And they’re an amazing – and often overwhelming – learning experience. The focal point of the learning are the courses, but for me, some of the best lessons are learned outside of the classroom.

One of the unique aspects of the experience is that, over the course of the camp, you have the chance to get know the instructors a bit, to get a sense of their distinct personalities.

It was during the faculty concert the final night, after having had the chance to get a least a little sense of who these folks were, that I observed something that would ultimately influence my own concept of mastery, and that would provide a guiding beacon for my own journey as a player from that point on.

Yes, the concert was fantastic. The music was terrific and inspiring, as you’d expect given the lineup of players like Mike Seeger, Brad Leftwich, and Mac Benford.

But the thing that stood out most for me about the playing of these master banjoists wasn’t their impeccable rhythm and timing. Nor was it their purity of tone or technical sophistication.

The thing that stood out was that, in spite of the fact that they were all playing essentially the same style and drawing from the same cannon of tunes, they all sounded very different. More than just different.

They all sounded like themselves.

No, I’m not just stating the obvious. What I mean is that their own unique personalities that I’d come to know a bit of over that weekend were now coming out, loud and clear, through their banjos. They’d somehow managed to take a piece of themselves, funnel it through their instrument, and transmit it out into the world.

It’s natural I think to view mastery as simply the accumulation of technical skill. It’s also the easiest thing to measure and quantify.

Yet, there are masters musicians whose playing is technically straightforward but moving, and there are musicians whose playing is technically advanced but forgettable.

Eddie Van Halen can surely navigate the guitar fretboard with greater speed and dexterity than Bob Dylan, yet both are viewed by many as masters. Why? Because they both know what they want to say on their instrument, and have the technical skill needed to say it.

And the same is true of Adam Hurt. Get to know him a bit, and you’ll hear him loud and clear in the music he plays. His playing is undeniably rooted in tradition, yet also undeniably delivered in his own voice.

Technical skill, then, is a necessary but insufficient condition of mastery.

It’s not about whether you know 300 tunes by heart, or how many notes per second you can play, or if you can solo between the 17th and 20th fret.

It’s about whether you’ve reached the point where you know what you want to say, and you have the chops needed to say it.

With these definitions out of the way, in the episodes to come we’ll get back to the business of how to build a brain that moves us toward the mastery we seek! For more about the “Masters of Clawhammer Banjo” course with Adam Hurt, go here.

— Go to Episode 10 —

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents

View the Brainjo Course Catalog