The Trial of Drop Thumb

In the world of clawhammer banjo, there are a few topics that, strangely enough, stir up heated debate.

And near – or perhaps at – the top of that list is the subject of drop thumb. There are two interrelated questions here that tend to stoke people’s rhetorical fire:

1. Should drop thumb be considered an advanced technique?

2. Should drop thumb be taught to an aspiring clawhammerist early on or later in their learning journey?

So let’s try to analyze the evidence dispassionately, free from bias or preconception, and see what l0gical conclusions we might arrive at…

Drop Thumb?!

First, let’s make sure we all know what we’re talking about.

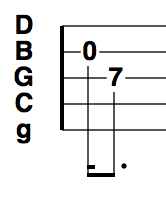

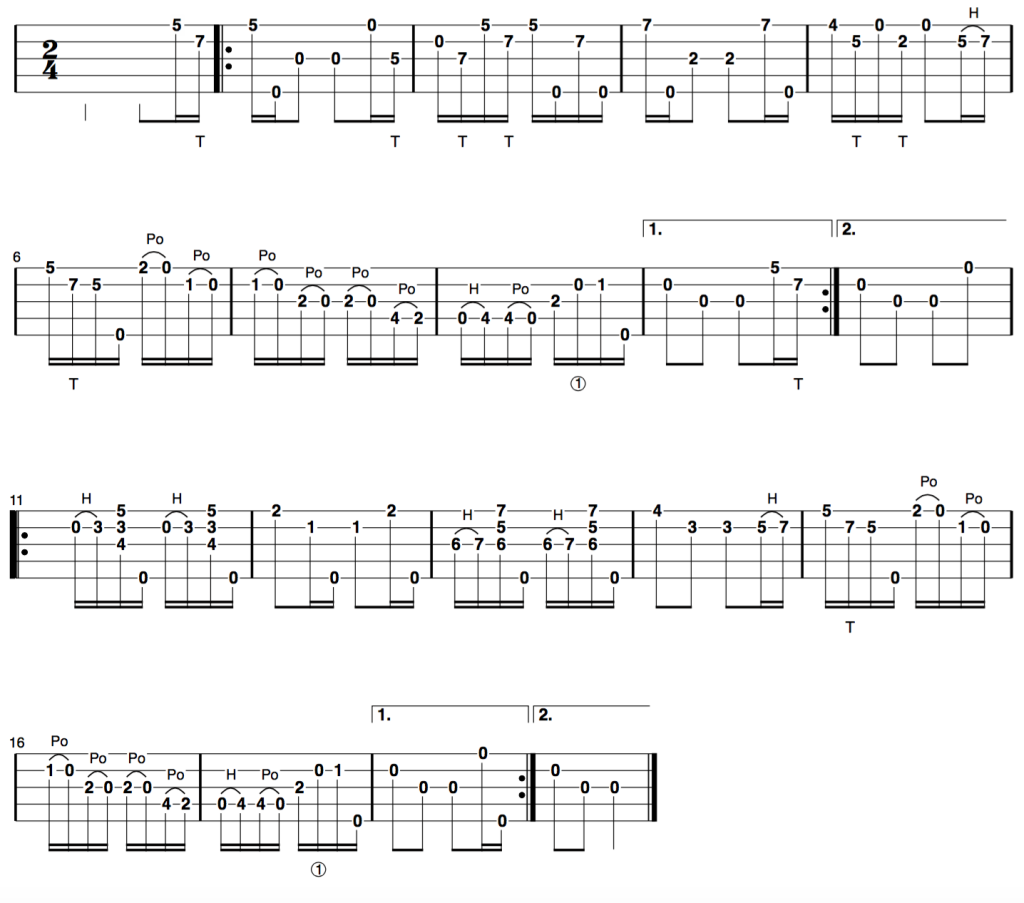

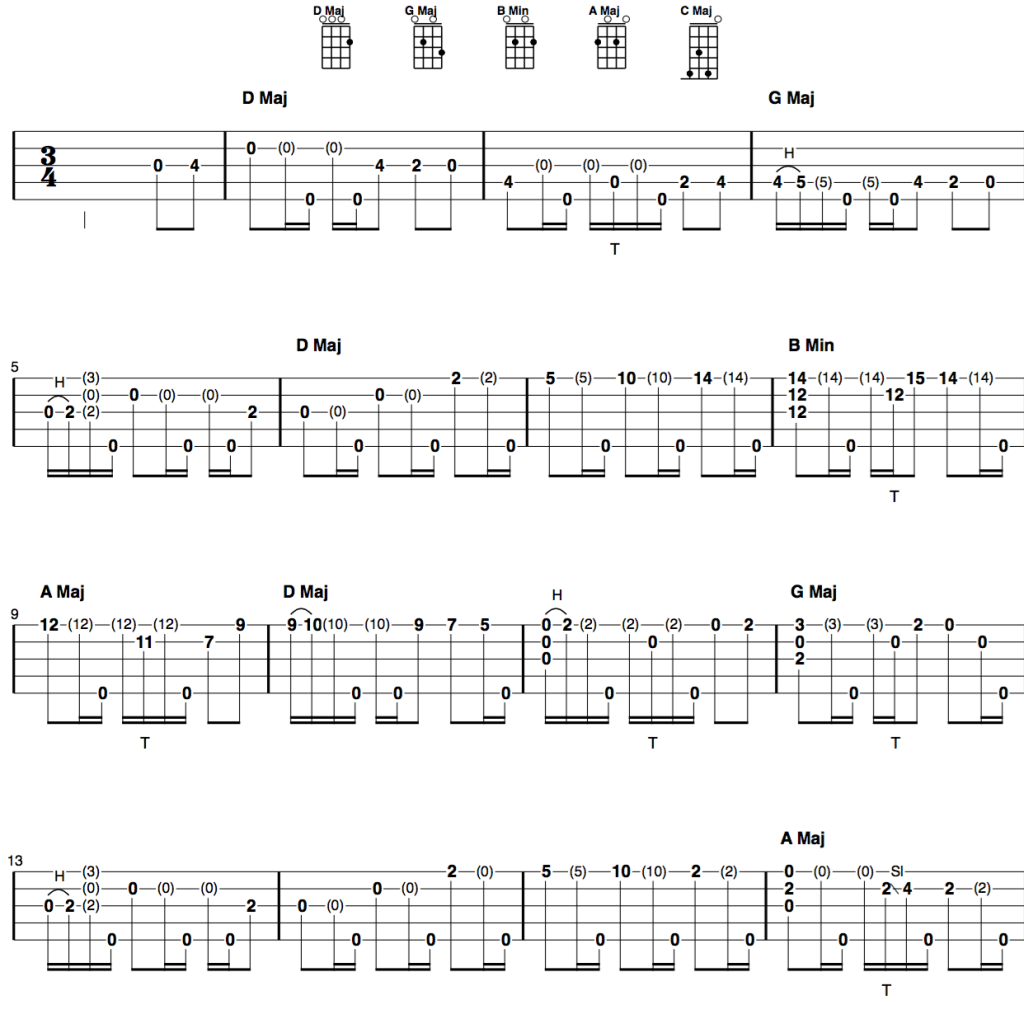

Drop thumb in the context of clawhammer banjo simply refers to plucking any string beside the 5th string with your thumb. In this case, you’re “dropping” your thumb to a string that’s below the 5th string. So if you play a note on strings 1-4 with your thumb, you’ve dropped your thumb.

So let’s first perform a rational analysis of the drop thumb technique in order to determine its relative technical difficulty.

Something Old or Something New?

Now, the basic clawhammer motion involves striking an inside string (or strings) with the picking finger, and then striking the 5th string with the thumb. So, in order to play clawhammer at all, you already must be capable of plucking the 5th string with the thumb. More specifically, you can pluck the 5th string after you’ve struck a note on any of strings 1-4 with your picking finger (covered in lesson 2 of the 8 Essential Steps To Clawhammer series).

Let’s then consider what you must do when dropping the thumb in a few common scenarios.

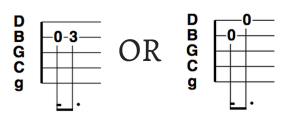

First, we’ll take the case of dropping the thumb to the 2nd string after you’ve struck the 1st string with your picking finger (be it the index or middle). As I said above, you already know how to strike the 5th string with the thumb after striking the 1st with your picking finger. So the only difference between the maneuver that you already know how to perform and the drop thumb to the 2nd string is the distance between your striking finger and thumb.

In essence, the only thing you must change from the technique you’ve already learned is simply the distance between your thumb and finger. But wait!

You actually don’t have to learn this, because you can already do it!

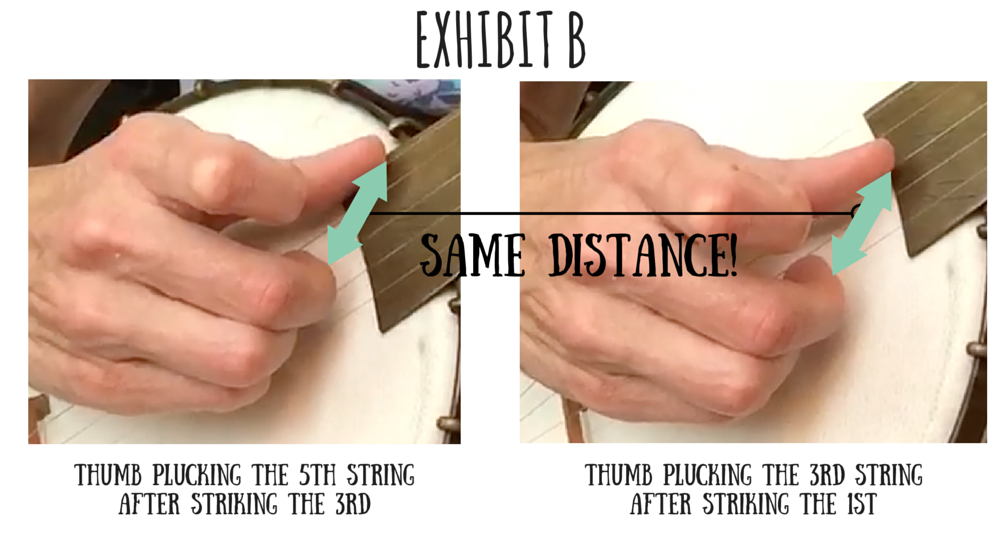

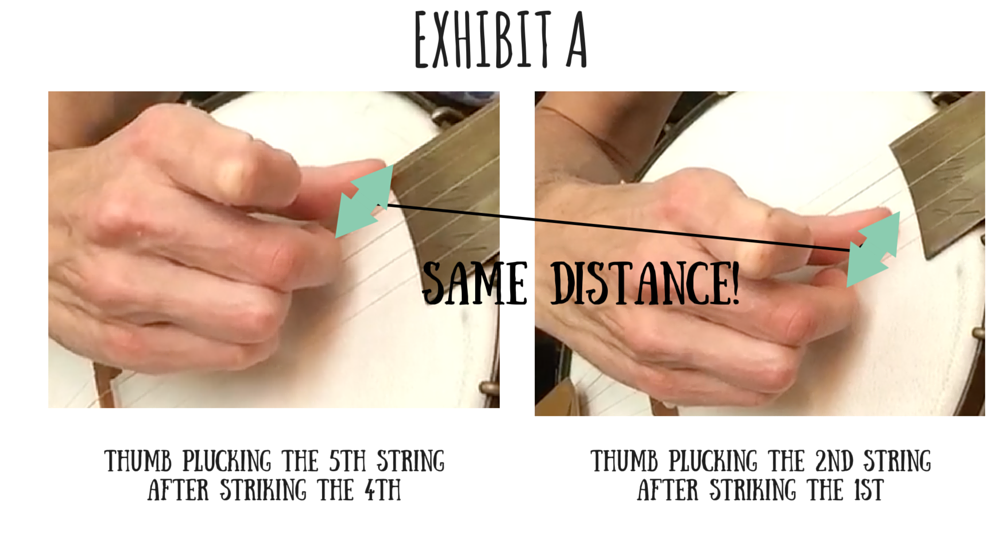

How is that? You already do it when you pluck the 5th string after striking the 4th string with your picking finger. The distance between strings 4 and 5 is the same is the distance between strings 1 and 2! To illustrate:

The shape of the hand is the same when plucking the 5th with the thumb after striking the 4th string, and when plucking the 2nd (i.e. dropping the thumb) with the thumb after striking the first. The only difference are the specific strings that are struck.

The shape of the hand is the same when plucking the 5th with the thumb after striking the 4th string, and when plucking the 2nd (i.e. dropping the thumb) with the thumb after striking the first. The only difference are the specific strings that are struck.

Likewise, the distance between the finger and thumb when dropping the thumb to the 3rd string after playing the 1st is no different than the distance between plucking the 5th with the thumb after striking the 3rd string. And so on.

So the fundamental technique for drop thumb (changing the distance between thumb and striking finger) is one that you already know.

The only real difference between striking the 5th and striking an inside string is that you have to be slightly more precise when coming down to pluck with the thumb in order to avoid the other strings (since there are no strings to avoid when coming down to pluck the 5th string with the thumb).

Drop Thumb In Context

Anyone who learns the basic clawhammer stroke must start from scratch. And, as anyone who has done this knows, the clawhammer stroke itself is quite counterintuitive and awkward in the beginning.

Yet, with persistence, you got it. And going from zero prior downpicking experience to playing the clawhammer stroke is a far greater learning chasm to cross than the slight alteration in thumb accuracy needed to drop the thumb to the inside string.

In other words, if you’ve learned the clawhammer stroke, you’ve already tackled a learning feat more challenging than drop thumb.

So, in summation, there are some marginal adjustments that must be made to the stroke you already know to make drop thumb work, but, the difference between that minor adjustment and going from never having played to learning the clawhammer stroke is huge.

THE VERDICT

Drop Thumb should not receive any special treatment, as it is no more advanced technically than the other foundational elements of clawhammer banjo.

So if it’s indeed true that drop thumb is no more advanced a technique than any other aspect of banjo playing, then why is it that it has the reputation of being so?

Drop Thumb and The “Beginner’s Mind”

To answer this question, we need to introduce a bit of Zen Philosophy into this discussion, specifically the concept of “Shoshin”, or beginner’s mind. Bear with me.

In the beginning stages of learning about a new subject, or learning a new skill, everything feels awkward and unfamiliar. This comes as no surprise, and so you expect things to be hard at first. As our familiarity and expertise grows, however, things start getting a bit easier.

In the case of learning to play an instrument, as some of those technical elements move from the realm of conscious incompetence to unconscious competence, things start getting a lot easier. And more enjoyable.

But what happens when you’ve reached that point of hard-won ease, and suddenly you’re once again confronted with all the beginner’s awkwardness all over again?

It feels worse than it did originally, because you feel like you should be past that stage. Moreover, because the other technical elements now feel easy by comparison, you mistakenly label the new awkward thing as intrinsically MORE difficult. Because that’s how it feels.

It’s seems a natural part of human nature, once you’ve reached a certain level of competence in an endeavor, to stay at that level and not push forward. Pushing forward requires conquering new challenges that require you to return to those early feelings of awkwardness. Feelings you expected to have in the beginning, but don’t expect to have now.

And this is exactly what happens to folks who don’t learn drop thumb early on. In my experience, the main difference between those who say drop thumb is difficult and those who don’t understand the fuss is when they tried to learn it.

Those who tried learning it early on found it no more challenging than all the other stuff they’d been doing. Those who tried learning it later on found that drop thumb, compared to the other techniques of banjo playing they’d now mastered, felt really awkward (of course it did!), naturally leading them to the conclusion that it was an especially challenging technique.

Apparently the Zen Masters recognized this phenomenon long ago. Not only recognized it, but realized what a significant impediment it can be to continual growth and progress. Keeping a beginner’s mindset, no matter where you are on the timeline of mastery, is key to ensuring that you don’t stagnate and plateau, which is the larger lesson here.

Personally, I’ve found it to be a valuable concept, and one I remind myself of often. I don’t ever plan to stop learning and growing, but committing to this process requires confronting new challenges virtually every day. Challenges that may make me feel inept, and that tempt me to simply return to playing the things I already know and do well.

But maintaining the beginner’s mind reframes that struggle entirely – what could be viewed as a personal failing is instead seen as critical to your growth. It is transformed from something demoralizing and resisted to necessary and welcomed.

So, concluding with the final summation:

1. The best time to learn drop thumb (provided it’s something you’d like to learn) is early on in your learning journey.

2. Maintaining the beginner’s mind is a key component to continual growth and progress.

If you’re ready get started learning how to drop thumb right away (the easy way!), then sign up for Breakthrough Banjo and get crackin’!