Episode 19: The Perils of Confusing Style & Technique

Episode 19: The Perils of Confusing Style & Technique

The moment has arrived. You’ve resolved to learn to play clawhammer banjo, and it’s time to commence with the first lesson.

But a choice must be made, you are told.

And not any ordinary choice.

It’s arguably the most important choice you’ll ever make in your banjo playing career, a fate sealing decision that will forever alter the course of your playing.

Choose wisely, and the halls of banjo fame await you.

Choose poorly, and your future is dark and bleak, thick with frustration and disappointment.

So….what’s it gonna be?

BUM-DITTY

OR

BUMP-A-DITTY?

What will you learn first?

OR……what if you really don’t have to choose at all?

What if turned out that the very problem that this choice supposedly either created or solved had nothing to do at all with which choice you made, and everything to do with the fact that you’re being asked to make such a choice to begin with?

Getting Technical

First, let’s outline some goals. Our chief objective with any musical instrument is to set the sound making parts in motion in ways we find pleasing to our ears. That’s simple enough.

And doing so typically involves a set of movements of the right and left hands. For clawhammer banjo, we have a particular set of well established, battle tested movements that are great for making pleasing banjo sounds. These are the techniques of clawhammer banjo.

There’s a set of techniques for each hand, and they are:

Picking hand techniques:

- the hammer strike (striking down with the back of the nail of the picking finger to string single strings)

- the brush/strum (striking across multiple strings in rapid succession)

- the thumb pluck (plucking an individual string, from 1-5, with the thumb)

Fretting hand techniques:

- basic fretting (holding down a string just behind a fret to generate a specific note)

- the hammer on

- the pull off

From Grandpa Jones to Kyle Creed to Frank Proffitt, these are the technical fundamentals of the clawhammer player. They do not vary from one player to the next.

Yet each of these 3 players – and any accomplished player, for that matter – sounds entirely unique. How can that be?

Because each player makes his or her own unique decisions about how to combine those techniques together when they play. When a single person or collection of people has a consistent manner in which they make those decisions, then we identify this set of consistencies as their “style” (individual style in the former case, regional style in the latter).

One component of those decisions involves what rhythmic patterns to use. These patterns are just sequences of picking hand movements that repeat.

For example, one player may favor a hammer-thumb-hammer-thumb picking pattern (“bump-a-ditty”) throughout his playing, whereas another may favor a hammer-brush-thumb (“bum-ditty”) pattern throughout hers. Some may choose a different pattern altogether.

Again, it’s that kind of choice – about how to combine the techniques of clawhammer – made on a consistent basis (within a tune, and from tune to tune) that comprises any given style.

So….to reiterate: Techniques are the elemental movements of playing. Those movements can be combined into patterns. And the consistent use of particular patterns defines a playing style.

Non-Blissful Ignorance

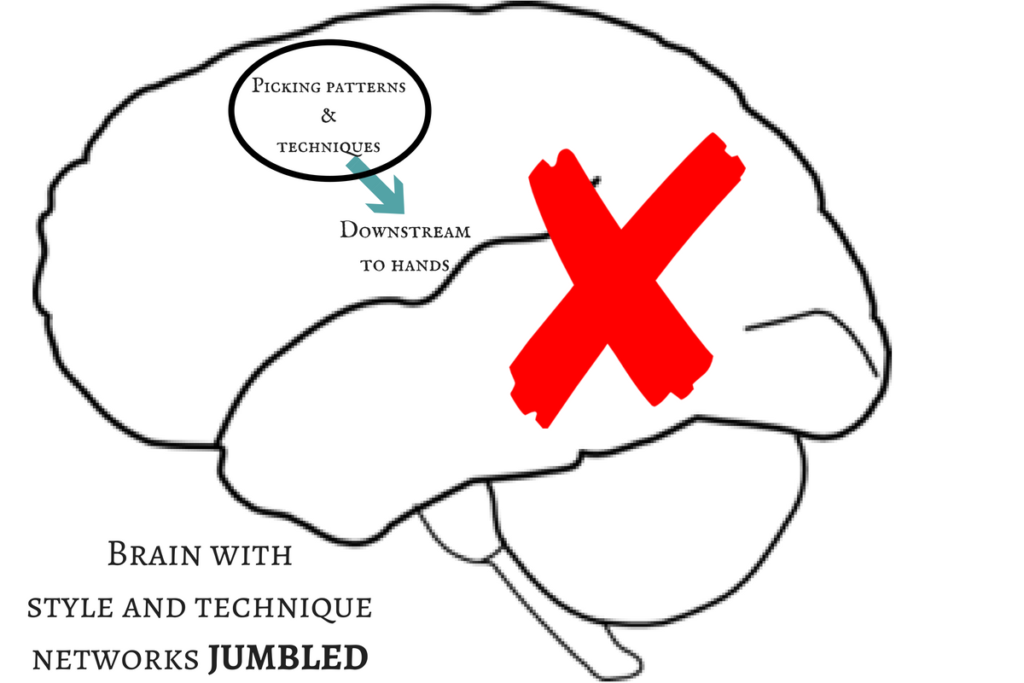

So why does this distinction matter? Because ignoring it can spell the difference between building a brain that opens the door to the entire range of possibilities within the realm of clawhammer, and building a brain that limits you to a single offshoot.

And, all too often, this distinction is ignored entirely. As a result, style and technique are all lumped into a single unit from the beginning, setting the player up for future frustration.

Remember, we’re only as good as the neural networks, or “zombie subroutines,” that we create through practice. Meaning the subroutines we create will ultimately determine the landscape of what’s possible in our playing.

The bum-ditty stroke, for example, consists of 3 separate technical elements (hammer-brush-thumb). If you lump all those techniques into one thing from the get go, guess what your brain is going to do? Lump them together as well.

So each time your brain makes a call for a hammer strike, what’s it sending down pipeline next? The strum.

Having been learned as a single unit, those 3 techniques are forever linked in the substance of the brain. This is what we told our brain we wanted it to do, because we started by learning a pattern (i.e. combination of techniques), rather than learning each technique in isolation.

And because these techniques are inextricably linked, it becomes exceedingly difficult for us to combine those techniques into anything other than that first pattern we learned. Again, this is not a matter of how gifted we are as musicians, it’s simply an expected biological consequence of how we practiced.

The problem wasn’t choosing the wrong pattern to begin with. The problem was in choosing ANY pattern to begin with.

This choice only matters if you don’t make any distinction between style and technique in the learning process. Because yes, if you don’t make any distinctions and start with learning picking patterns right out of the gate, then that initial decision will lock you to a particular style. In this case, mixing and matching techniques at will and at the speed of music becomes a biologic impossibility.

Unless you’re willing to go through the process of starting over from scratch, which most are loathe to do, you will have limited yourself to a particular style from the very start.

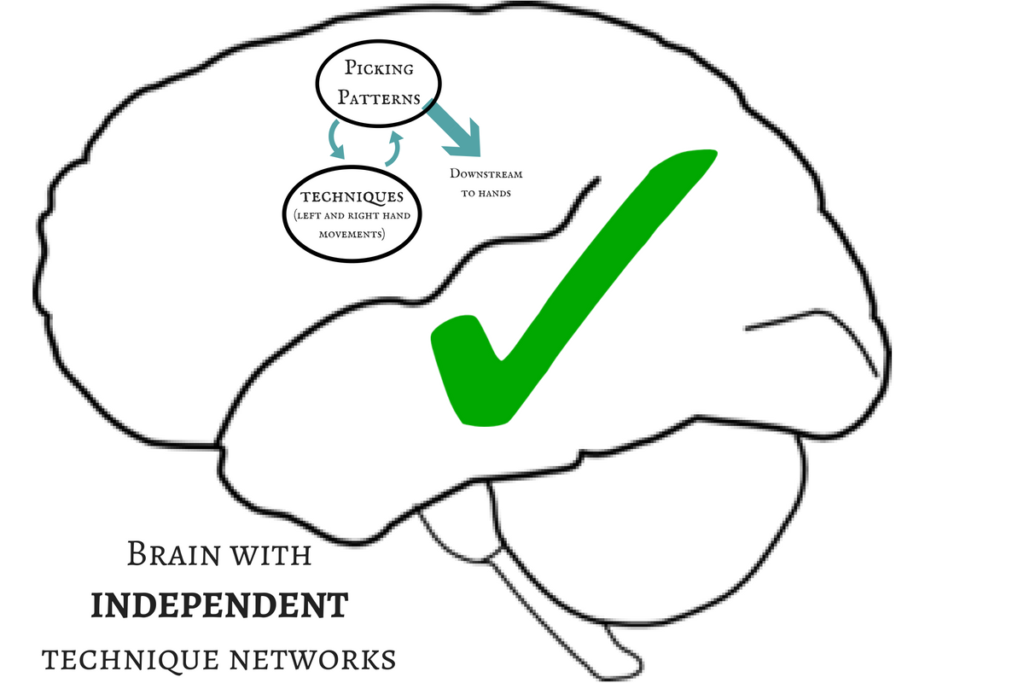

As I’m sure you’ve figured out, there is an alternative. An alternative that doesn’t constrain your future at all. On the contrary, it keeps open the entire range of stylistic possibilities indefinitely.

And that is to first create these technical networks INDEPENDENTLY from any particular pattern or style (as is done in the “8 Essential Steps to Clawhammer Banjo” series).

With independent, sovereign zombie subroutines for each of our elemental movements, we’re free to mix and match them at will, combining them, at the speed of music, into whatever pattern we choose.

Begin not with patterns, but with the fundamental elements, and our fateful choice laid out earlier makes no sense. Now that the patterns are no longer mutually exclusive, the entire debate becomes meaningless.