Episode 18, Part 2: How To Accelerate Your Progress 10-fold (while practicing less)

A Failing System

It’s no secret that medical school involves the memorization of heaps of information, and that making good grades in medical school is largely correlated with how much of that heap can be crammed into one’s cranium prior to testing time.

Fortunately, by the time I’d gotten to medical school, I’d already developed my own battle tested note-taking and study system for cramming large quantities of information into my cranium, honed during my preceding 16 years of schooling.

Here was that system:

Step 1: Write out all the lecture material (in extremely small handwriting).

Step 2: Read through the notes, highlighting in yellow all the important stuff I didn’t yet know.

Step 3: Read through the highlighted portions again, quizzing myself as I went. Highlight the important stuff I still didn’t know well in a different color.

Step 4: Repeat step 3 multiple times, using a different color highlighter each time until left with only a few remaining highlights.

By the morning of testing day, I’d typically have around ten highlights left, which I’d read through in about 5 minutes for one final review.

Now, if you’d casually glanced at these multicolored and micrographic notes, you’d have likely thought them the product of a mind gone mad. But that madness had a method, and this system was very reliable. With it, I knew that getting a good grade was simply a matter of putting in the work.

But here’s one small GIGANTIC problem with that system: I remember almost none of it now.

And I can assure you that none of my classmates do, either.

The fact that I don’t remember what I studied then isn’t the product of some personal inadequacy, but an inevitable part of human biology. It’s an expected consequence based on what we know of how our brain works.

Sadly, it turns out that the best method for achieving high marks on tests – cramming – is of no use when it comes to actually retaining that tested information over the long term.

Ultimately, I did learn and remember what I needed to know for my profession, I just had to use entirely different methods to do so.

If you’ve been following this series for any length of time, you know by now that the conventional much of how we go about learning new things, including the conventional approach to learning a musical instrument, is typically uninformed by the process of how we learn and how our brain’s change to incorporate new information. The purpose of the Brainjo is to incorporate what we know about the science of learning and brain change so that we learn smarter, not harder.

Perhaps nowhere is this disparity between how things are typically done and how things should be done greater than in our approach to remembering new material. Especially in school.

I’m sure you can relate to my experience. You likely spent thousands of hours of your childhood strapped to a classroom desk. Chances are you too only remember the tiniest fraction of what was covered in those classrooms (likely only because you found it interesting enough to revisit some point later on).

You see, the challenge we all face as we try to continue to cram new stuff into our minds is this: how do we put new stuff in there and KEEP it there, while still holding on to the old stuff. The more time you spend learning new stuff, the less time you can spend revisiting the old stuff to make sure it’s still there. So it seems that, eventually, something has to give.

This is true with learning music as well, of course, especially as we continue to add new music to our repertoire. In the early going, when we know only handful of tunes, we can practice them all in a single practice session.

As time goes on and the number of learned tunes reaches the tens or hundreds, however, things get complicated. Practicing every one each time you sit down with the banjo is entirely impractical.

No surprise then that many folks, after learning roughly 20 to 30 tunes, hit a wall. They plateau, and don’t progress much further.

One reason for this is they spend all their practice time trying to hang onto those tunes, leaving no time for anything else.

How then do you solve this dilemma?

The Science of Remembering

My note-taking method outlined above was a partial solution to this problem. By identifying and highlighting the information I still didn’t know each time I ran through it, I eliminated the inefficiency of reviewing already learned and memorized (at least in the short term) material.

But, like I said, almost none of it stuck with me over the long term.

It was a step in the right direction, but there was something missing.

To understand what was missing, we need to review a bit about how or brain’s remember. Or, more precisely, how it forgets.

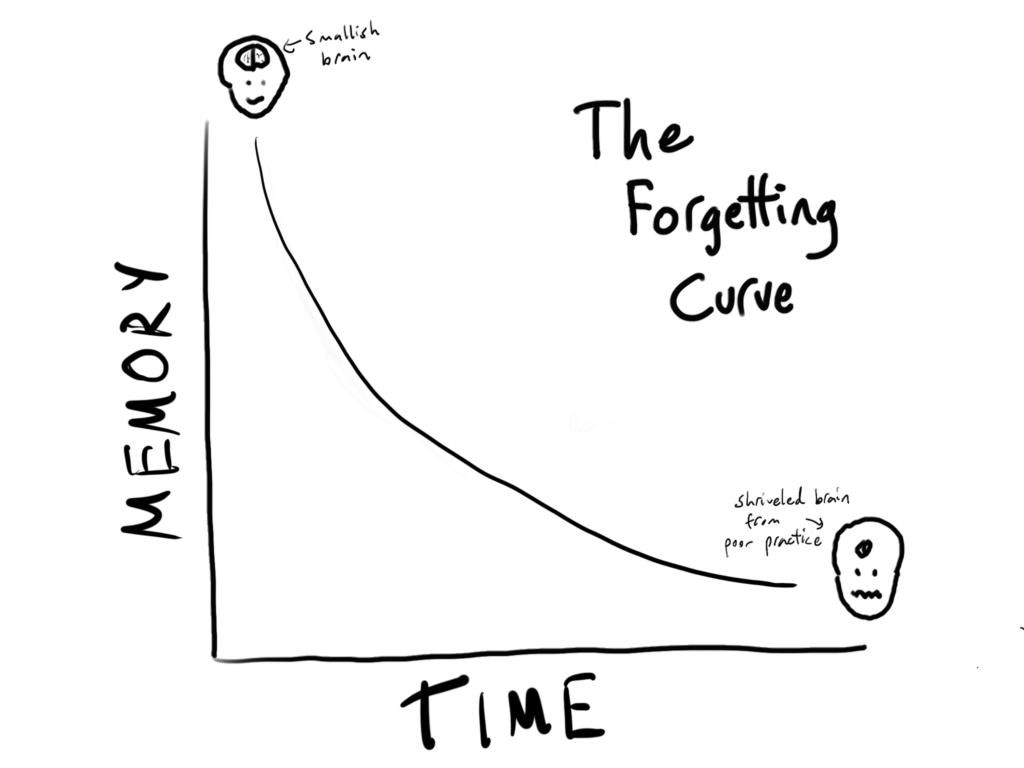

The Forgetting Curve

The above “forgetting curve”, as the name implies, shows how a new memory “trace” in the brain degrades over time. Specifically, we’re talking about something – be it an event, fact, etc. – that we deem worth remembering (since most of the flotsam and jetsam of everyday life would be wasteful to commit to memory)

As time passes from when the memory is first encoded in a neural network, things start to get squirrelly. As indicated by the downwardly sloping curve, the memory slowly degrades over time until it vanishes. Unless, that is, something comes along to cause it to fire again.

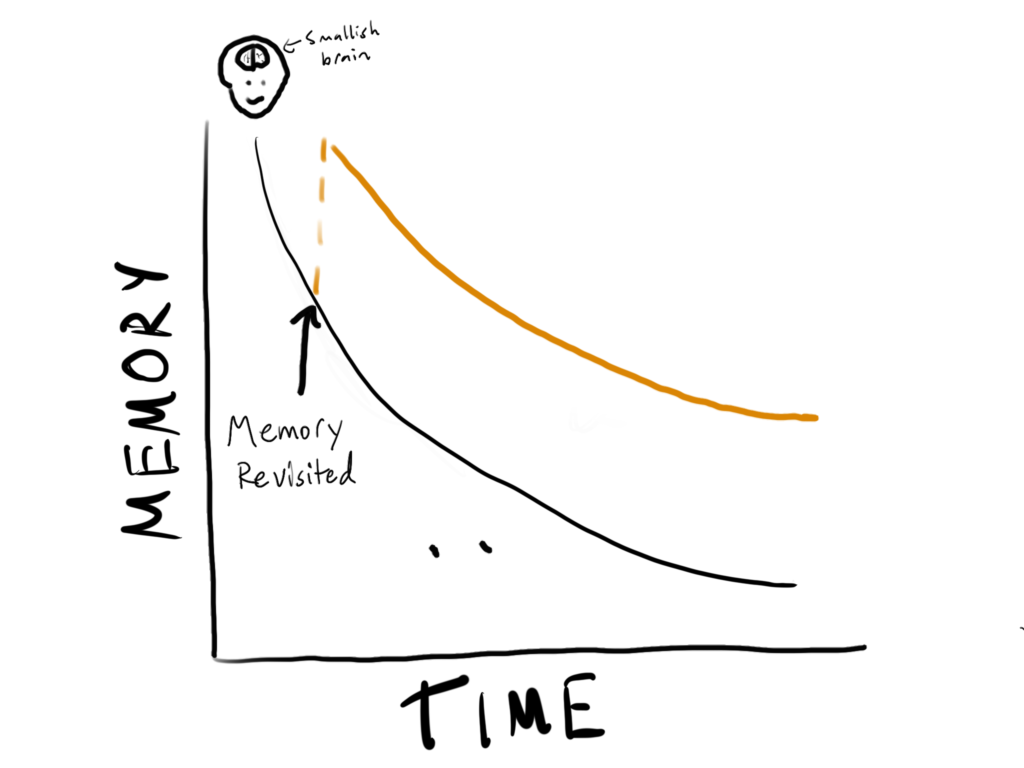

The best defense against the forgetting curve is to visit that memory again. But here’s the counterintuitive part: WHEN you actually revisit that memory makes all the difference.

Revisit the memory too soon and your time is entirely wasted – you won’t increase the odds of remembering it down the road one single bit.

Revisit the memory too late and..well…it’s too late! The memory trace has vanished, and you must essentially build it again from scratch.

So when is the very BEST time to revisit it? Right before you’re about to forget it.

A large body of research has shown there to be an ideal window of time for revisiting a memory – a “goldilocks zone” – that’s not too close but also not too far from when you encoded the memory.

What’s so special about this goldilocks zone is that if you revisit that memory during it, the forgetting curve not only begins anew, but with a slope of forgetting that isn’t as steep. Reviewing it once means you can wait a good bit longer before you need to visit it again:

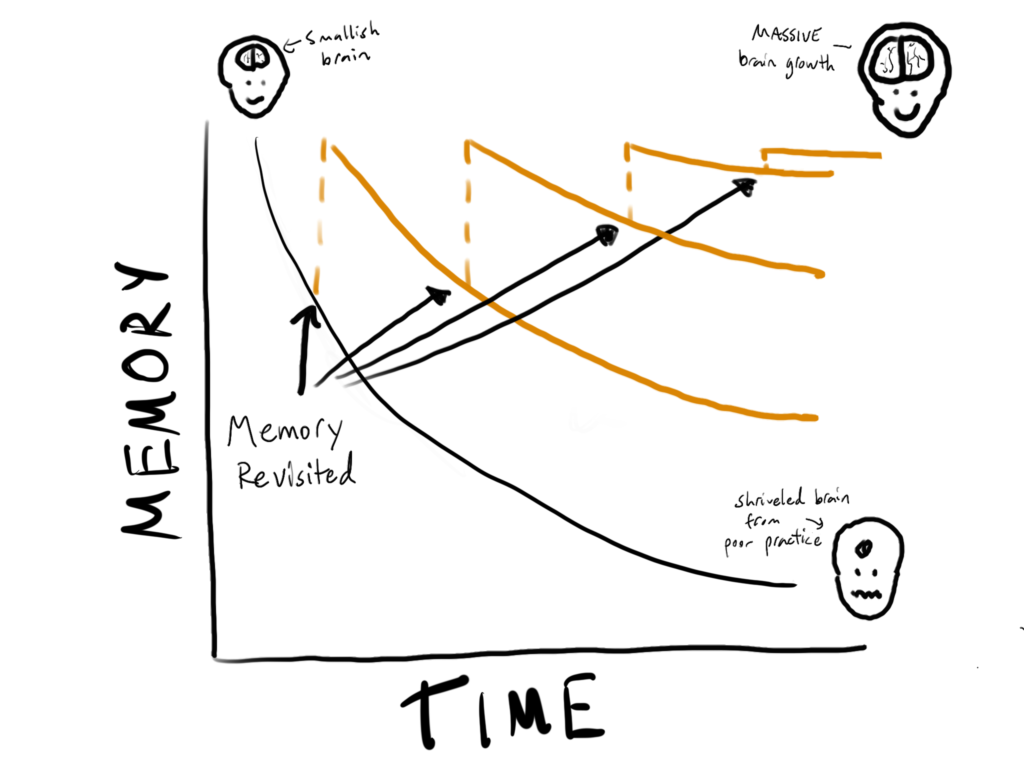

And each time you revisit the memory, you achieve the same effect, until after enough iterations the curve effectively becomes a straight line:

Ultimately, through these well timed revisitations of the initial memory trace, you’ve made the memory a literal part of you, as much a part of your brain matter as your mitral valve is a part of your heart matter.

Since this phenomenon of human memory was first discovered in 1885 by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, several different systems have been devised to take advantage of it, most under the label of “spaced repetition.”

Spaced repetition has been harnessed to greatest effect in the field of language learning, where’s it’s been shown to be hands down the most efficient method for building vocabulary, beating conventional approaches 10-fold or more. But, since it’s a universal principle of memory, it can be applied to most anything that you’d like to learn and keep with you.

And while it’s true that the precise time windows are much more well established for remembering vocabulary words than for remembering music, the same general principles still apply; principles we can use to our own advantage to optimize the chances of remembering the music we worked so hard to learn, and to spend a minimum of wasted time doing so.

The most obvious place to use it is in the building of your banjo playing repertoire, especially as your ability to learn new material improves, and the amount of stuff you ‘d like to remember grows.

There are many potential ways you could implement the spaced repetition approach, but here’s one example of how this can be done:

- Make 5 stacks of notecards. Label one stack “daily,” one “every week,” one “every 2 weeks”, one “every month,” and one “memorized.”

- Write down the names of the tunes you’re in the process of learning.

- Each time you learn a new tune, add it to your practice daily file (or any frequency you’d like – these are just the tunes that you know least well).

- Practice the tunes in your practice daily file every day. If you play a tune well, move it to the “every week” stack. If you don’t, it stays in the daily stack.

- Practice the tunes in the “every week” stack once a week. If you play a tune well, move it to the “every 2 weeks” stack. If you don’t, it goes back to the daily stack.

- Practice the tunes in the “every 2 weeks” every two weeks. If you play a tune well, move it to the “every month” stack. If you don’t, it goes back to the daily stack.

- Practice the tunes in the “every month” stack once a month. If you play it well, move it to the “memorized” stack. If you don’t, it goes back to the daily stack.

Over time, your “memorized” stack should grow. These are the tunes you can count on as yours for the long haul.

As you can imagine, this type of procedure is the sort of thing computers are quite good at. And so I should point out here that there are multiple applications available that can implement a spaced repetition algorithm (including iOS and Android apps).

With these, you just create the cards (digitally), and the program takes care of programming your schedule (here’s a link to Anki, perhaps the most widely used flashcard spaced repetition system).

Spaced Out Space Outs

As I said, the obvious place where you could employ this technique is in growing the number of tunes you can play.

But, I think an even more powerful, effective, “two-birds-with-one-stone” way to use it is for is in the rehearsal of tunes you can visualize yourself playing.

The process is exactly the same, except that instead of playing the tune on your banjo, you just visualize yourself playing it through.

Since this is somewhat of an advanced technique, I’d recommend you get comfortable with the visualization practice methods discussed in part 1 before attempting it.

The advantages of this approach are that you can still reap the memory benefits that would come with physical practice, while simultaneously supporting the creation and development of those neural networks that support musical fluency. And there’s virtually no equipment required. Just take your flashcards wherever you go, can you can capitalize on a proven method for making massive progress anytime, anywhere.

Then, once you’ve created these sound to motor mappings through some smartly timed visualization practice, you’ll also likely find your ability to learn and remember new material will skyrocket.

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents