The Laws of Brainjo

Episode 15: The Secret to Memorization

Imagine this scene:

You’re gathered in a small circle with a handful of other musicians at an old-time jam. Only one of them is a fiddler, but he’s a seasoned one. As the one responsible for carrying the melodic line on each tune, he’s leading the show.

Which means if he doesn’t know the tune that’s called for, then it’s not gonna be played.

This will be a short jam, you think to yourself. Once you exhaust his repertoire of tunes, you’ll have to call it a day. Maybe you’ll make it an hour tops.

But an hour passes, and you’re still playing music. Two hours. Then three…

Amazingly, this fiddler seems to have an endless supply of tunes he can call forth at will.

“How about ‘Molly in the Foxhole’?” suggests the guitarist.

“Ooooh, haven’t played that one in years. How’s that go?”

“It starts out dada da da dad…”

“Got it!” he interrupts, and off he goes.

How is this possible, you think. I’ve been at this banjo thing off and on for a couple years now, and only know about 10 tunes by heart. This guy knows hundreds, maybe thousands of tunes. Have I just happened upon a musical savant?

The above scenario plays itself out in old-time jams around the world with regularity.

For the uninitiated, seeing a veteran musician call forth a seemingly endless supply of tunes can be a mind blowing experience. And the natural conclusion is to assume you’ve just born witness to a superhuman feat of human cognition.

Yet, this sort of thing is not that unusual at all. In fact, most master musicians possess a vast library of tunes they can call up at a moment’s notice.

But how on earth is this possible? Most early players struggle mightily to remember just a few tunes. How could this memorization ability gap be so large? Does achieving mastery of an instrument also magically impart an exponential expansion in one’s memory?

Before we delve further into the realm of musical memory, let’s first consider, for the sake of comparison, another domain of artistic expression: painting.

The Expert Advantage

Imagine two different individuals, Pierre and Brad. Pierre is an expert painter. Brad is a complete novice.

Both are given an assignment to re-create a work by a master artist. Only they’re not allowed to look at the original painting when doing so. Rather, they must paint it from memory.

Pierre studies the painting for a few minutes, then begins work on his piece. In short order, he produces an impressive re-creation of the original.

Brad, on the other hand, is a bit overwhelmed by the task. I have no idea how to paint all this, he thinks.

Then, to his delight, he discovers that there exists a video of the original artist painting the picture he must recreate.

I don’t need to know how to paint at all, Brad reasons, if I can just copy all of his movements, mine will turn out like his!

So Brad begins studying the video, with the goal of committing to memory every stroke of the brush that was made to produce the work he must copy. But soon, with the full magnitude of his task finally sinking in, Brad abandons this approach. There’s no way he can commit all of this to memory, he realizes.

Brad takes a look at Pierre’s work and is astonished to find that, to his eye, it’s almost indistinguishable from the original. Mouth hanging wide open, Brad wonders how on earth Pierre achieved such a feat of memory.

Taking the Easy Road

Brad’s idea, in theory, wasn’t a bad one. The surest way to recreating the original work of art would be to make EXACTLY the same movements that the original artist made in painting it.

The problem, as I’m sure you recognize, is that pulling this off would require a feat of memorization beyond anyone’s capability. This just isn’t the type of memory the human brain excels at. It’s a logical, if entirely impractical, idea.

Yet, Pierre was able to recreate the painting from memory. His approach to doing so, however, was entirely different.

Through a lifetime spent mastering the art of painting, Pierre has acquired an expansive artistic vocabulary of concepts (house, tree, forest, etc.), along with the motor programs required to translate those concepts into images on the canvas.

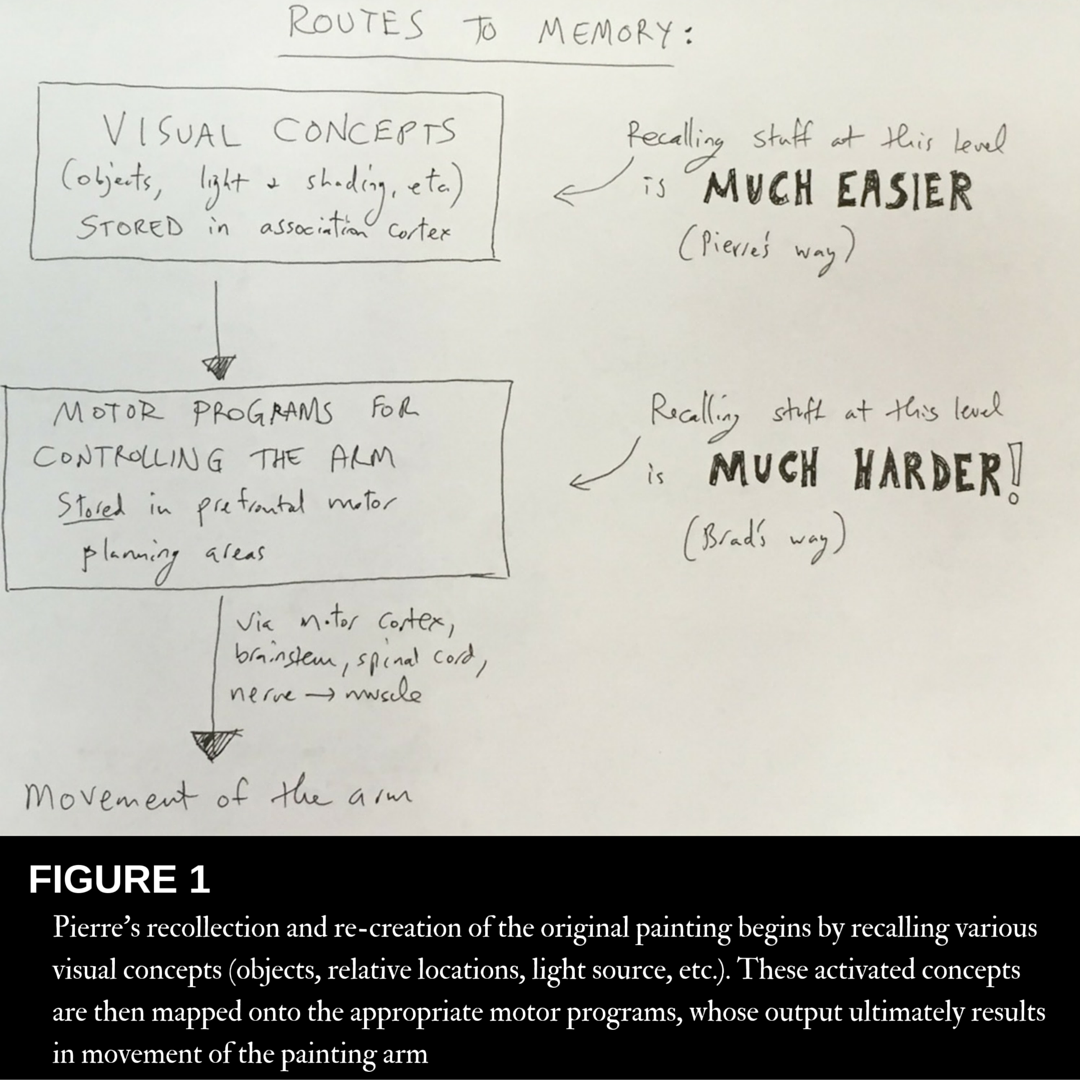

If we diagram out Pierre’s pathway from recall to painting (the boxes representing function specific neural networks), it looks like this:

Remembering images, especially those that could exist in the real world, is something we’re all quite good at. Take the following painting, for example:

After only a short glance, you’ve already extracted (whether you tried to or not) the relevant details from it. You know there’s a cottage, a forest, a lighthouse, an ocean. You also know their relative locations, along with the time of day, the color of the sky, and so on.

You’re able to take the vast body of experiential knowledge you’ve acquired about the world you live in and use that as a powerful memory aid. You can remember the scene at the conceptual level, creating a scaffolding upon which to hang your memory of it.

Pierre can use this type of conceptual memory to his advantage when trying to recreate the original work. Brad cannot.

Our Musical Memories

Now let’s turn our attention to musical memory. To begin, here are two memory challenges for you.

First, below is a video presenting a string of letters. Play through the video once, and then try to recite back the entire sequence of letters.

If you found that ridiculously difficult, you’re not alone.

Second, below is an audio clip of a melody. Play through the video once, and then see if you can hum the melody back to yourself after listening.

A bit easier, I imagine?

Both of these videos are actually representations of the same tune. The sequence of letters in the first video are the notes of the tune. The second is the audio of those notes played on the banjo. Below is a video of the notes along with the audio.

Remembering the string of letters was difficult, to put it mildly. Remembering the melody? Far simpler.

Once again, the first type of information – a [seemingly] random string of letters – is hard for anyone to remember.

The second type of information – a melody that conforms to the rules of Western music – is something every human brain is much better at remembering. Yet, both are representations of the same thing.

And therein lies the secret to our fiddler’s seemingly superhuman powers of recall.

A Happy Accident

In Episode 11, we came up with a definition of musical fluency, the mark of a master musician:

Brainjo Law #13 : Musical fluency and improvisation is predicated on the ability to map musical ideas (and the neural networks that represent them) onto motor programs.

Like the master painter who, through years of [the right kind of] practice, has built up a library of neural mappings between visual concepts and motor programs for controlling a paintbrush, the master musician has done something analogous, mapping musical concepts onto motor programs for operating a musical instrument.

In both cases, the creation of these networks allows the fluent artist and musician to tap into a type of memory that we’re all quite good at: remembering a real-world image in the former case, a melody in the latter.

Yet, these routes to memorization are biologically inaccessible to the novice painter or player.

The development of fluency transforms memorization from something arduous (remembering the movements of a brush or the notes on a page) to something natural and effortless (remembering a scene or a melody).

Before fluency has developed, the only possible avenue you have to memorize a tune is to commit the tab or the movements to memory. And this feels hard BECAUSE IT IS HARD! For everyone.

(RELATED: Click here for the system I recommend using to memorize tunes before you’ve reached fluency)

It doesn’t get easier one day because your memory gets better. It gets easier when you begin to develop fluency (as defined above).

Here, as with the ability to play faster, the ability to memorize new tunes easily occurs not through any sort of dedicated memory practice, but rather as a byproduct of the creation of brain circuits that support musical fluency.

Which is why building those circuits is the key to mastery.

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents