The Laws of Brainjo, Episode 11

How To Build An Improvisational Brain

In the last installment, I introduced the concept of the Timeline of Mastery, the learning sequence through which anyone must pass as they develop expertise in a subject.

The gold standard for this type of thing is the timeline of language learning. It’s the most reliable and efficient model for human learning ever created. And, fortunately for us, the many similarities between language and music means there’s tremendous insight to be pulled from this model for our own learning purposes.

When it comes to language, the ultimate destination, the marker of mastery, is fluency. One way to define fluency is the ability to take ideas in mental space (“thoughts”) and translate them into speech, in a manner that both seems and feels instantaneous.

Fluency can also be described as “improvisational speech”: the ability to take the building blocks of language and connect them in combinations that allow for the expression of ideas that are novel, personal, and specific to a situation.

And this is also about as perfect a definition for fluency on a musical instrument as I can imagine. The fluent musician is able to take musical ideas in mental space and translate those — seemingly instantaneously — into the sounds of an instrument.

With the language learning model as our guide to improvisational fluency with music, what then would be considered the prerequisites for linguistic fluency? What are the neural networks that must be created to support this skill?

Improvisational Networks

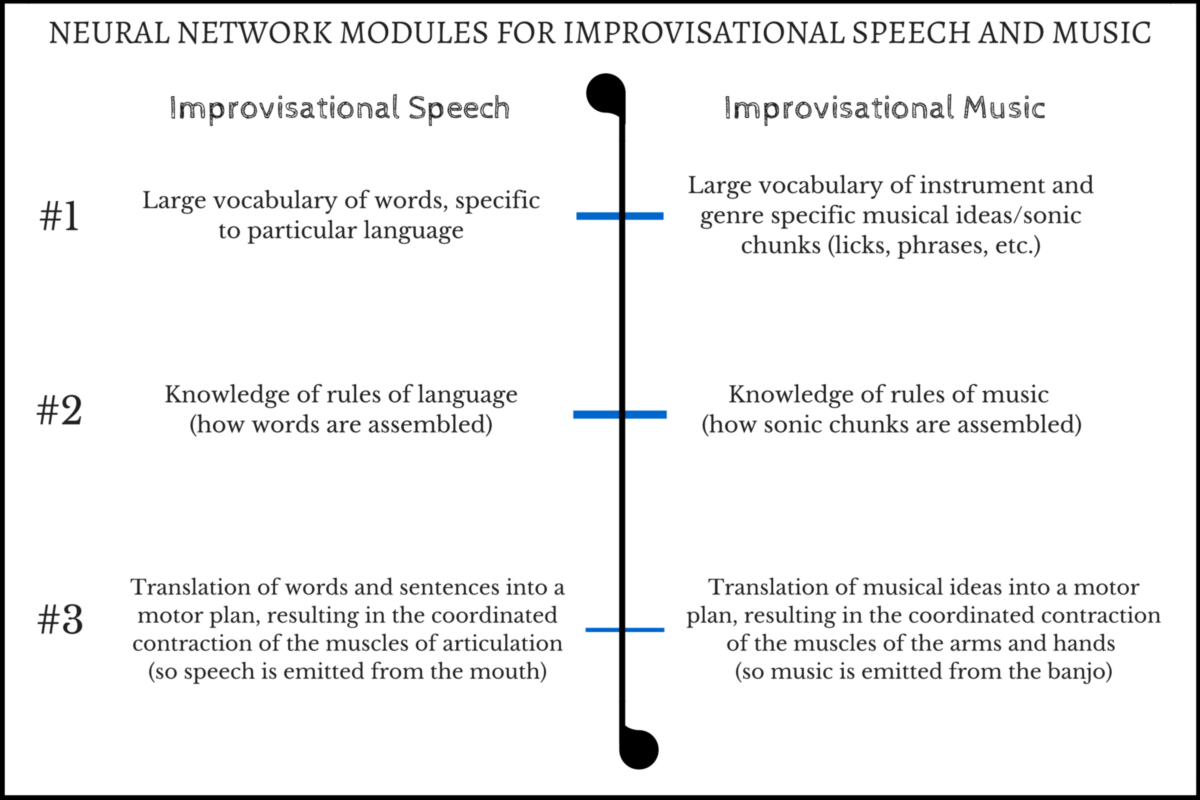

The neural networks required for improvisational speech are:

1. A sufficient vocabulary of words, stored as sonic representations, so that mental concepts can be communicated accurately.

2. Knowledge of the rules of language (grammar), so that the words are assembled in ways that others can understand.

3. The ability to emit all the words in that vocabulary via the coordinated contraction of the muscles of articulation.

In the brain, we know that all of this involves the sophisticated and mind-blowingly complex communication amongst billions of neurons distributed across multiple, dynamic neural networks.

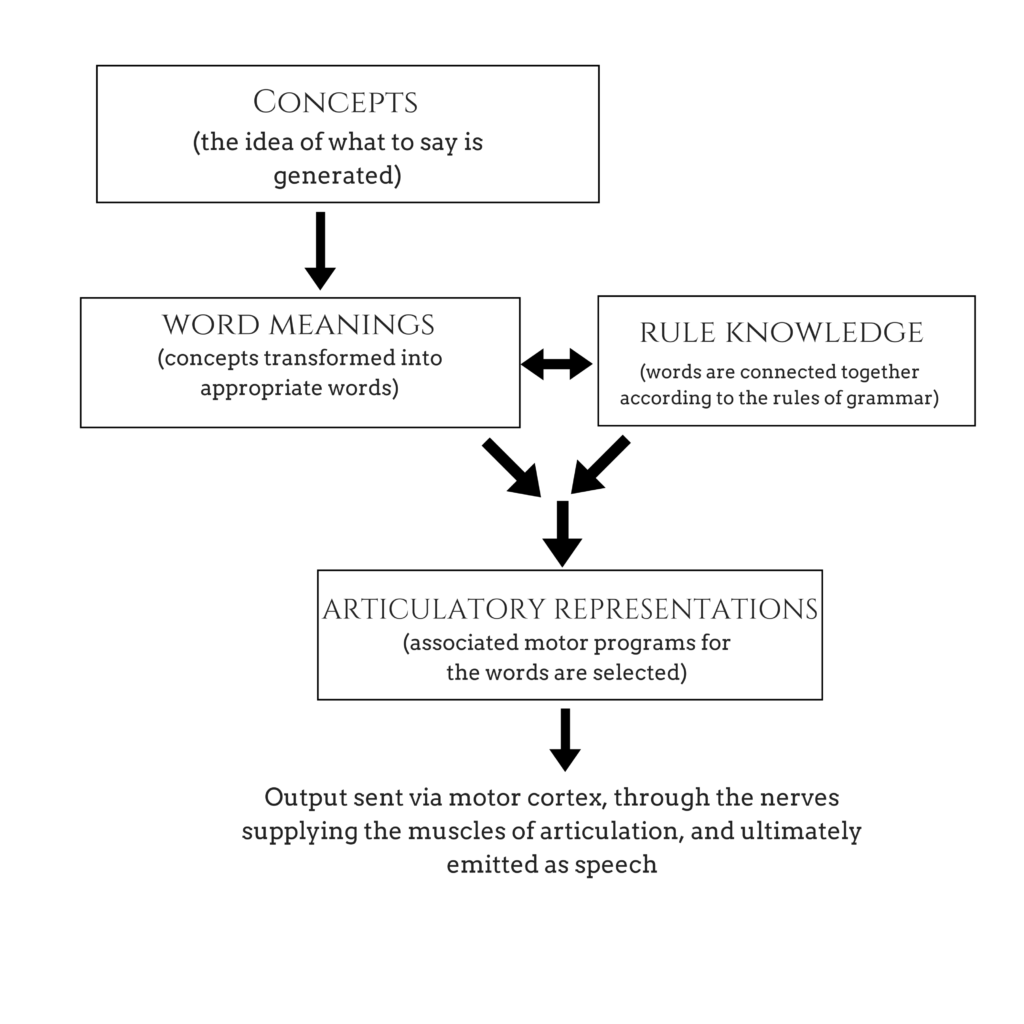

Generally, these networks can be represented as follows:

If we wish to create similar neural machinery inside our noggins – machinery that will ultimate support musical fluency — then we’d be wise to pay attention to how these networks are built.

How then do you build a really big vocabulary of words?

By reading, and by listening to others whom you think are good communicators. Much of this happens just by living around other fluent humans.

How do you build a big vocabulary of musical ideas?

Once again, by listening A LOT, especially to the people whose music you enjoy most.

How do you learn the rules of language?

Again, much to your grammar teacher’s dismay, you also did this by listening. You listened, and the master pattern recognizer/decoder inside your skull figured it all out.

Likewise, here again, through copious listening, you’ve already developed a sophisticated grasp of the rules of language, or music theory (regardless of whether you’re consciously aware of or can formally articulate it). In some cases, formal study can enhance that understanding further, expanding the scope of what you can express on your instrument (just as knowing the rules of grammar can, in some cases, make you a better writer)

How do you learn to emit the sounds of language through the muscles of articulation?

By practicing, in logical sequence, the articulation of the sounds of language, beginning with the most basic and simple to produce phonemes (the aahs and oohs of those first cooing sounds of a 3 month old) and moving to ones of increasing complexity, followed by syllables, words, and phrases.

How do you learn to connect music in the mind to movement of the limbs?

Here we have the meat of the learning process for music, the stuff we do when we say we’re “practicing,” and, not coincidentally, largely the focus of this particular series on the Art and Science of practice. And this corresponds to the third network in the summary table below:

A mature network of this nature, the kind that can support the type of fluency described earlier, is one that can map musical ideas onto the motor networks that then send the appropriate output to the muscles of the arms — output that produces the coordinated contractions that result in those musical ideas coming out through the banjo.

Brainjo Law #13 : Musical fluency and improvisation is predicated on the ability to map musical ideas (and the neural networks that represent them) onto motor programs.

Musical, and improvisational, fluency ultimately requires two primary components:

1. The ability to conjure pleasing musical ideas in ones mind.

2. The ability to realize those ideas in realtime on the instrument.

So if developing the neural networks that support fluency primarily involves copious listening and the development of instrument-specific motor skill of increasing complexity, is there still a role in all of this for written music in the learning process?

Find out in Episode 12: Is It Safe To Use Tab?

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents