A little bit of cyber-digging will make clear that there are some things about the origins of this week’s tune that we still don’t know, and may never know.

That said, here are some of the things I think we can be reasonably certain of:

1) Quince Dillon was a confederate soldier and fifer.

2) Fiddler Henry Reed got the tune from Quince. Whether Mr. Dillon also composed it appears to be unknown.

3) It’s a very cool tune.

4) Playing this tune – in particular that “high D” note in the A part which, let’s face it, you HAVE to nail – is much less stressful on a fretted instrument (fiddlers may jokingly refer to this as “Quince Dillon’s High E, or High C,” etc. – an allusion to the difficulty in nailing that big jump up the fingerboard on a fretless instrument..).

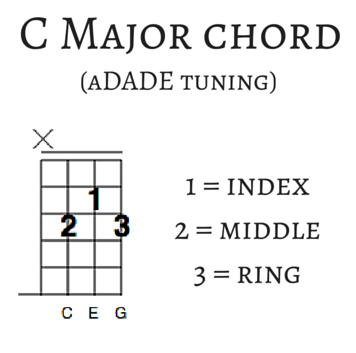

Furthermore, with both that big two octave stretch in the A part and the use of the C chord, this tune seems intent on reminding you that it’s not your ordinary fiddle tune.

Which, of course, is a big part of its charm!

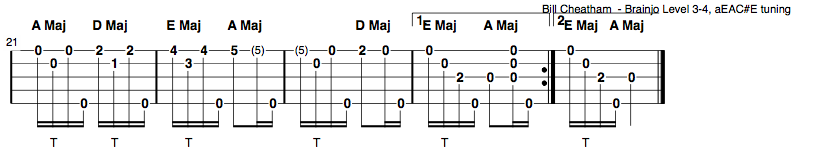

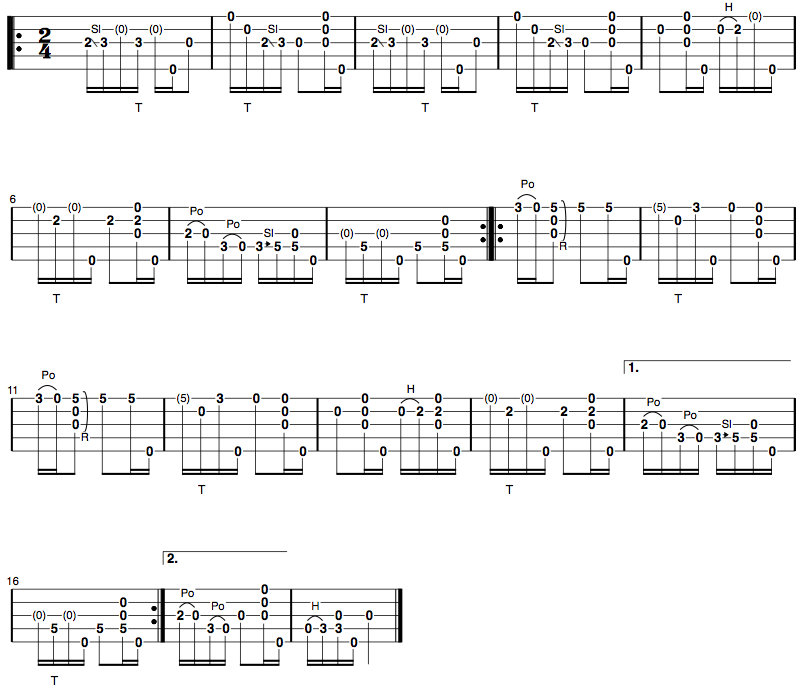

Speaking of that C chord, which you may have never had an occasion to play out of “double D” tuning, here’s what that shape looks like:

I tend to keep my hand in this shape in the 19th and 20th measures for ease of pickery.

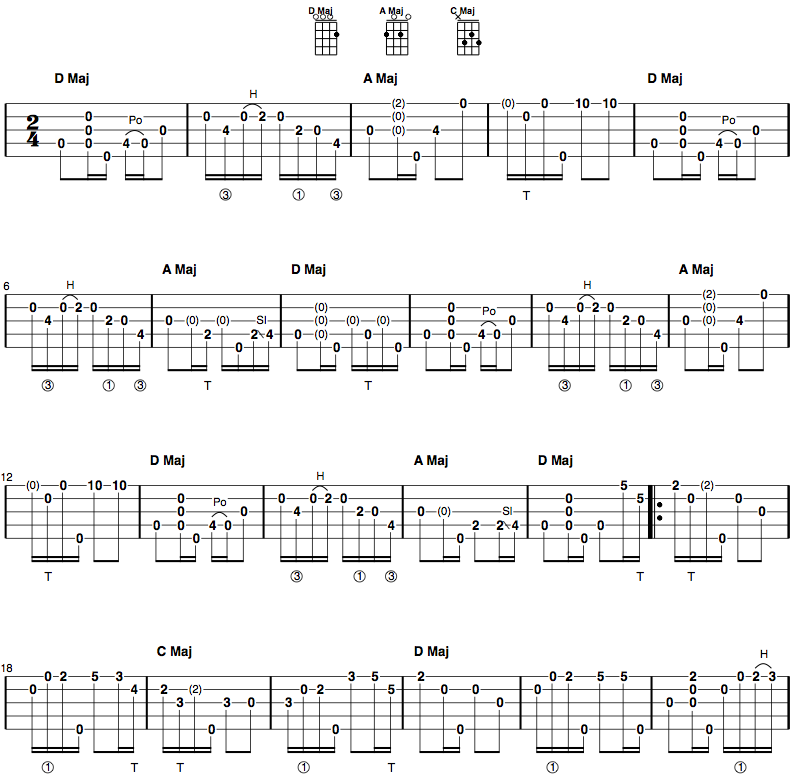

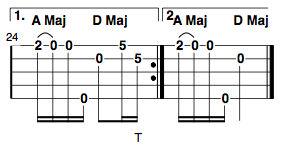

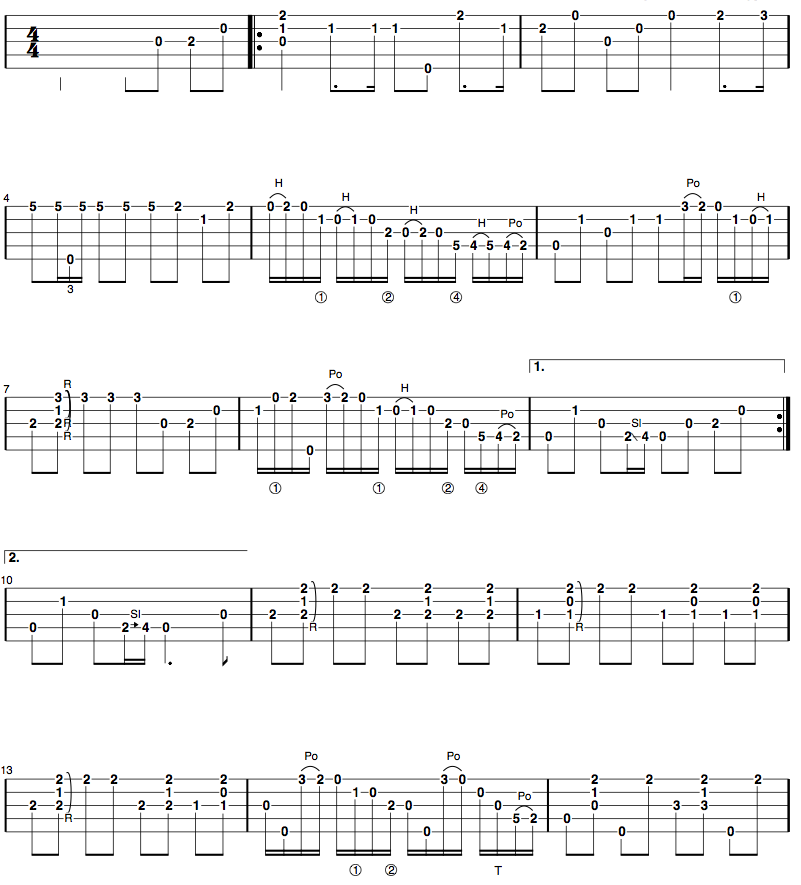

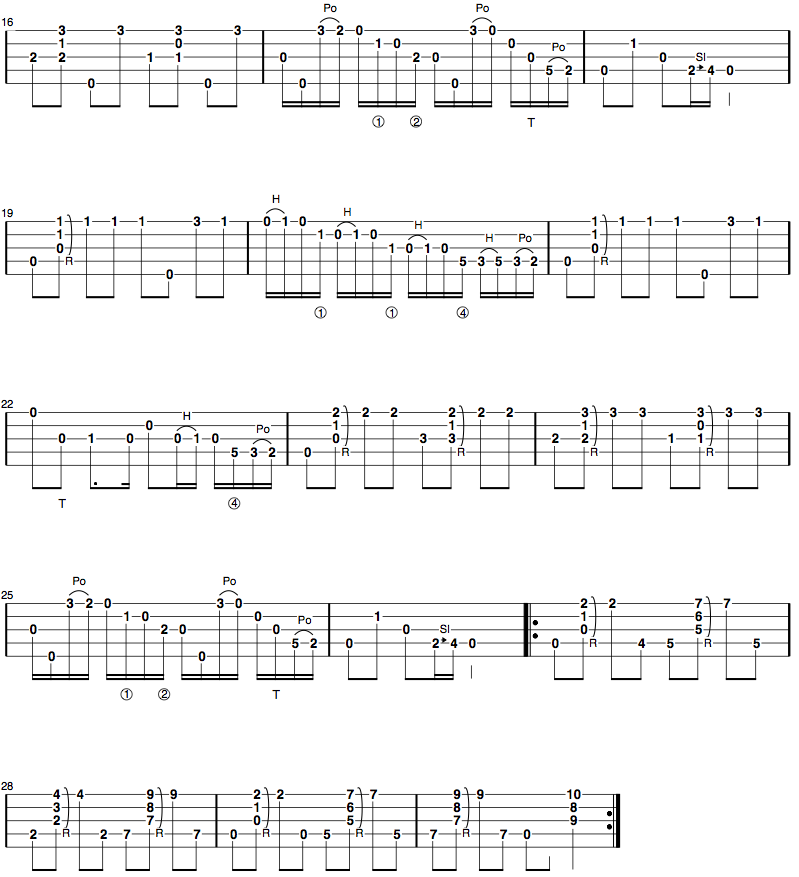

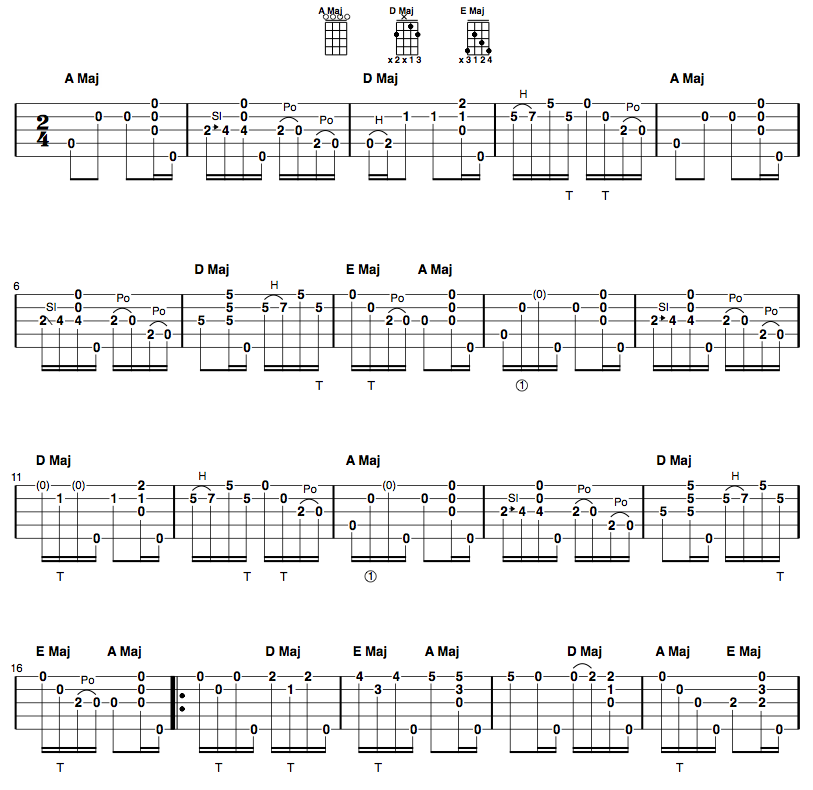

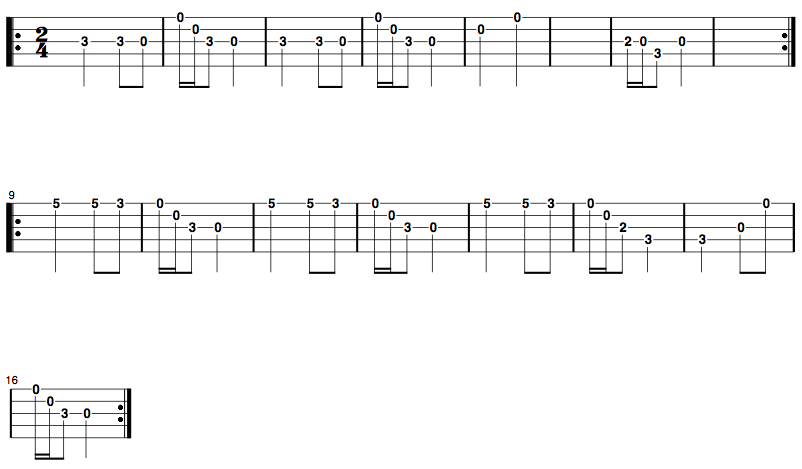

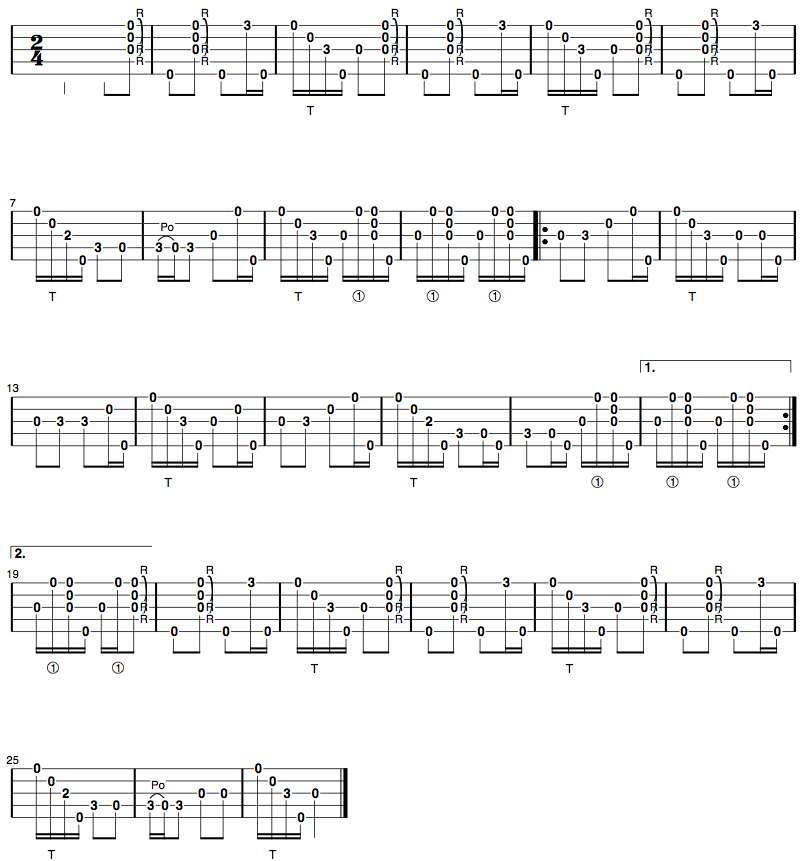

Quince Dillon’s High D

aDADE tuning, Brainjo level 3-4

Notes on the tab

Notes in parentheses are “skip” notes. To learn more about these, check out my [free] video lesson on the subject.

For more on reading tabs in general, check out my complete guide on reading banjo tabs.