Clawhammer Banjo Tune of the Week: “Shady Grove”

Bacon and eggs.

Abbott and Costello.

Modal tunes and banjos.

There’s just something special about modal tunes played on the banjo. It’s one of those pairings where each party is elevated by the presence of the other. Modal tunes just make the banjo sound extra good, and vice versa.

So, as you may have guessed, this must mean that there’s a modal tune up for today’s tune of the week. Not just any modal tune, but arguably the most popular modal tune of all, one that’s spread itself well beyond the confines of the Appalachian old-time tradition. That tune….is Shady Grove.

And while it’s been rendered in a multitude of instrumentations over the years, I’m personally still partial to the way it sounds all by its lonesome on the banjo. Vocal accompaniment is optional.

Like I said, there’s just something special about the banjo and modal tunes.

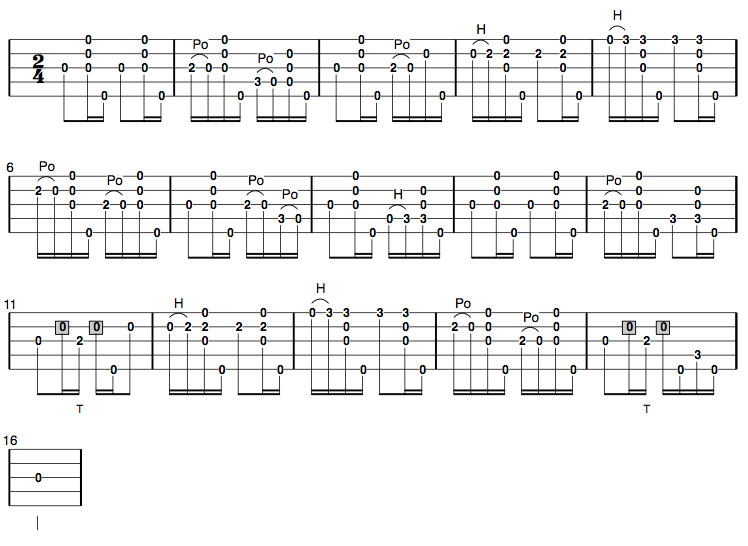

Shady Grove

gDGCD tuning, Brainjo level 2-3

Notes on the tab

As you can see, I’m playing this one on the gourd banjo, which is tuned down to dADGA. However, this is the same relative tuning as G modal, or gDGCD, which is where I’d usually play this tune on a modern, steel string strung banjo.

Skip Notes: The notes in the shaded box are “skip” notes, meaning they’re not actually sounded by the picking finger. Instead, you continue the clawhammer motion with your picking hand, but “skip” playing the note by not striking it (this is a technique used to add space and syncopation). The fret number you see in the shaded box is the suggested note to play should you elect to strike the string.

The Immutable Laws of Brainjo: Deconstructing the Art and Science of Effective Practice (Episode Two)

Episode Two: How to Play “in the Zone”, and Why You Want to be There (Part One)

“I was playing out of my head”

“It was like the banjo was playing itself”

“I was in the zone”

Ask a master – regardless of domain – what it feels like when they’re performing at their very best, and these are the kind of descriptions you’re apt to hear. The words may be different, but the underlying sentiment is almost always the same: an alternate state of consciousness has been reached, allowing for effortless and optimal performance.

Over the years, different names have been used to describe this state of being: “the zone”, “flow state”, “zen-like”. In these moments, the conscious mind is quiet, sometimes leaving the player with the impression that they’re no longer involved in the playing. He or she may even feel a bit sheepish about taking credit for the resultant performance.

But the zone isn’t territory reserved just for masters. On the contrary, these moments of effortless execution can happen to anyone, at any stage in the learning process. In fact, you’d be wise to make it a habit of seeking them out often, just as the masters do.

Here’s why.

The Bird’s Eye View of Learning

Nobody is born knowing how to play the banjo. This is obvious. Even Earl had to build his own banjo playing brain.

This means that every component of playing the banjo, from plucking a string cleanly to fretting notes with the fingers to forming chord shapes, must be learned.

More specifically, this means that a dedicated neural network – a set of instructions for how to perform that particular skill, written in the language of neurons – needs to be created for each and every technical component of banjo picking. The brilliant thing about the human brain is that it can create those instructions for itself, based entirely on the inputs it’s given through practice (which in reality are the inputs it provides itself…consider your mind blown).

In Chess and Tai Chi master Josh Waitzkin’s book The Art of Learning, he likens the learning process to hacking a path through dense jungle with a machete. At first the task is arduous and taxing, with great expense of time and effort.

During this stage, the conscious mind is fully engaged, frantically trying to cobble together an ad hoc motor program (i.e. a set of instructions for movement) out of existing multi-purpose neural machinery. All cognitive resources are brought to bear on the task at hand.

If we place a subject at this stage of learning in a functional brain imaging scanner, we see brain activity all over the place (indicated by the colors, which signify increased blood flow to the corresponding areas):

With repeated practice over time, things change. A lot. Ultimately, if the learning process goes well, the brain creates a customized neural network for the learned activity. When the task is performed now, we see both a shift in the location of the brain activity, along with a marked reduction in the number of neurons involved:

This neural network that’s been created not only consumes fewer resources, but much of it also now exists beneath the cortex (it is “subcortical”). Thinking back to our jungle analogy, a path has now been cleared, allowing us to walk down it effortlessly, without any contribution from the conscious mind. Through practice, a new pathway has literally been carved in the brain.

The Purpose of Practice

So what might this have to do with playing “in the zone”?

Everything. Playing “in the zone” can only happen after these paths have been cleared, after we’ve built neural networks specific to the corresponding activity through effective practice.

The truth is, you enter the zone all the time, everyday. Walking down the street, brushing your teeth, driving a car, fixing a sandwich – these are all learned skills you can perform while your conscious mind is engaged in something else (we take these activities, complicated as they are, for granted, precisely because they feel so effortless). Each of these activities has its own pathway carved in the brain, a dedicated neural network containing its set of instructions, built and reinforced through years of experience.

Creating these neural pathways is the reason we practice. Which brings us to the second law of Brainjo:

Brainjo law 2: The primary purpose of practice is to provide your brain the data it needs to build a neural network.

The goal of practice is not to get better right then and there. The goal is to signal the brain that we want it to change, and provide it the inputs it needs to do so effectively.

But this raises a critical point. If our brain is building new networks based on the inputs we provide, then we need to ensure that we’re providing it with the right kinds of inputs, at the right time. The brain will build a network, a set of task specific instructions, based on any type of repeated input. Provide the wrong kind of input, and we end up with the wrong kind of network.

Practice a sloppy forward roll over and over again, for example, and guess what you’ll end up with?

A “sloppy-forward-roll” neural network, that’s what. You’ve successfully carved a path, but the problem is it leads to the wrong place.

Knowing When (and When Not) to Move On

In the beginning, the temptation is always to go too fast. We’re excited and eager to start picking some good music, and we want to play it now!

But the danger here in going too quickly is that you move to more advanced techniques before the basic ones they’re grounded in have fully developed, before those pathways, which serve as the foundation, have been laid. Rinse and repeat this process, and you end up with a bunch of networks that don’t do what you want them to do. The result is frustration, and the only remedy is to start over from scratch.

But what if there were a way we could know when those pathways were fully formed, a way to know when it was safe for us to move onward to the next hurdle? As it turns out, there is.

In neuroscience parlance, when a skill no longer requires our conscious mind for its execution, it is said to have become “automatic”. This can be tested for experimentally by having a subject perform the skill in question while their attention is diverted elsewhere. If there’s no decline in performance, then the skill meets the criteria for automaticity. If performance declines, then more practice is needed.

So if we want to test for automaticity ourselves, we can steal this same strategy, which brings us to the 3rd law of Brainjo:

Brainjo Law #3: Work on one new skill at a time until it becomes automatic.

Now, I know what you’re probably thinking: How do I tell if a skill has become automatic?

As I mentioned above, automaticity is tested for experimentally by having a subject perform a learned task while paying attention to something else. Is there a way, then, for us to test this for ourselves, without any fancy high-tech equipment?

You bet there is! In part two of this series, we’ll cover a foolproof and indispensable method for testing for automaticity.

Go to Part 2 Now!

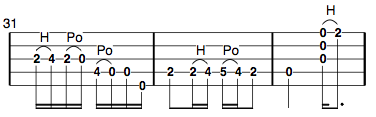

Clawhammer Banjo Tune of the Week: “Coleman’s March”

Legend has it that Joe Coleman, after whom this tune is named, was accused and convicted of stabbing his wife to death, though he claimed innocence till the end. En route to his execution, it was said the he played the tune we now know as “Coleman’s March” on his fiddle. According to legend, he then offered said fiddle to anyone who could play the tune as well as he (source: “The Fiddler’s Companion”).

For me, the melody of this tune alone is enough to get me all choked up. Throw in this anecdote and, well, you might as well stick a fork in me…

Anyhow, this is one gorgeous tune. And you don’t really need to do much more than stick to the melody to make it sound great. In fact, I find that the more I restrain myself from superfluous fanciness, the better it tends to sound.

You’ll note in the video that I play an “up the neck” variation on the A part, which I’ve also included in the tab below.

Coleman’s March

aDADE tuning, Brainjo level 3

Up the Neck A Part Variation

Clawhammer Core Repertoire Series: “Snowdrop”

Season 2: Solo Clawhammer Classics

Episode 1: “Snowdrop”

A New Chapter

Take notice fans of the Core Repertoire Series, we’re changing gears!

Up until this point in the Clawhammer Core Repertoire Series we’ve been focusing on jam classics, working on building up a stable of tunes to ensure that you’re prepped and ready for any old-time jam, wherever it may strike. And in the process, we’ve been pulling back the curtain to reveal just how these arrangements are constructed in the first place.

But you now have 16 jam classics in your stable, and that’s a lot of mouths to feed. Best we stop breeding more.

So, now it’s time to create an entirely new stable! And this time we’ll be filling it with solo clawhammer classics. Though some of these you may also encounter at your friendly neighborhood jam, all the tunes we’ll be covering in this series make for excellent stand alone clawhammer pieces.

In fact, some of them sound best as solo clawhammer pieces (which is why many of the ones we’ll cover have been featured in my “clawhammer tune of the week” series).

Which brings us to our first tune in the “Solo Clawhammer Classics” season of the Clawhammer Core Repertoire series: Snowdrop. First off, here’s how my final arrangement for this tune sounds:

As ambassadors for the banjo go, I don’t think you can do much better than Snowdrop. In a matter of 4-7 notes (depending on whose data you use), you can single-handedly wipe out virtually every preconceived notion and misconception someone may have about banjos and the people that play them.

There’s no ear splitting jangliness to be found here (though I happen to love ear splitting jangliness). Nope, just hyper-melodical-dulcet-toned sweetness.

Snowdrop is typically credited to Kirk McGee of the McGee brothers, who are the ones who first recorded it. Incidentally, Kirk actually played it fingerstyle, though these days you’re much more liable to hear it played by downpicking enthusiasts.

Step 1: Know thy Melody

First off, if you’re not familiar with this tune, take a listen to the above video enough times for you to extract and remember the melodic core of this tune. Don’t proceed onward until you can hum or whistle it. Once you think you’ve got it, it’s time to try and find it on the 5-string.

Step 2: Find the Melody Notes

Before you go note hunting, get your banjo tuned to “open C” tuning, which is gCGCE. For some of you, this may be the first time you’ve tuned your banjo here. All the strings are the same as “double C” (gCGCD) except for the first, which is tuned to an “E”. What you end up with is an open C major chord.

As with most alternate tunings, open C makes Snowdrop both easier to play and sound better. Win-win. Unless you break your 1st string tuning it up. Then it’s win-win-lose, which is still a respectable ratio.

So this is what I hear as the essence of Snowdrop:

And here’s what that looks like in tab:

What you’ll notice here – which will be a recurring theme in the “Solo Clawhammer Classics” edition – is that the melodic essence of this tune isn’t that far off from how our final arrangement sounds. Generally speaking, fiddle tunes – which is what we’ve covered thus far – are going to have the most number of notes per measure (playing a bunch of notes is a trivial matter on the fiddle, so they just can’t help themselves).

Most non-fiddle tunes, however, won’t be as melodically complicated. With fewer notes packed into each measure, these tunes will breath a little more.

Step 3: Add Some Clawhammery Stuff

Using our basic melody as a guide, we can now turn this into a very nice clawhammer arrangement quite simply. By adding some ditty strums after most of our melody notes along with a couple of well placed pull-offs, we now have a very respectable arrangement (Brainjo level 2 in terms of level of difficulty)

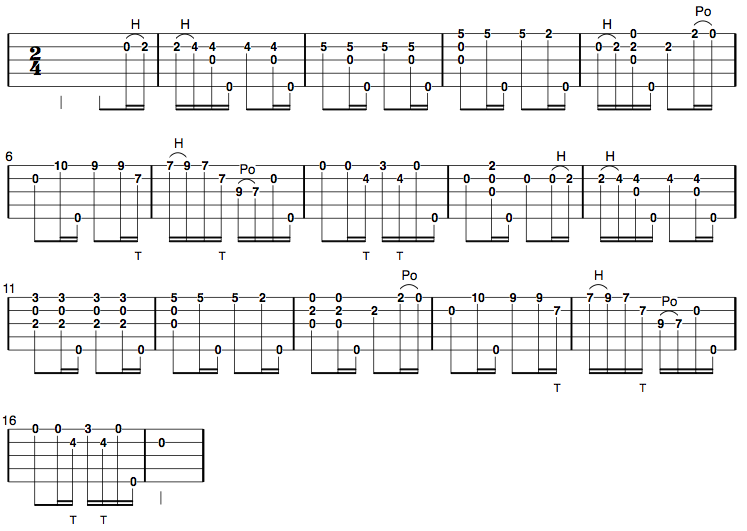

Snowdrop

gCGCE tuning, Brainjo level 2

(note the few instances here where you’ll want to form a bar chord at the 5th fret)

And here’s how that sounds:

As you can see, this version is built entirely on straightforward clawhammer techniques. Yet as you can hear, without adding in any fancy fretwork or right hand pyrotechnics we already have a version of Snowdrop that, if played with good timing and rhythm, sounds absolutely wonderful.

Step 4: Embellish to Suit Your Tastes

That being said, we’re all humans. Which means we like to monkey with stuff, and we like to make tunes our own.

So feel free to add your own stylistic embellishments to this core arrangement. You can hear mine in the first video above – feel free to steal liberally. Here’s the tab for that version (Brainjo level 3):

Snowdrop

gCGCE tuning, Brainjo level 3

Go to the Core Repertoire Series Table of Contents

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- …

- 71

- Next Page »