I must confess that, for most of my life, I knew virtually nothing about the minstrel era in American music.

Essentially, the term conjured up images of people dressed in outlandish garb that’d be widely considered offensive in this day and age, making some crude jokes, with maybe a dash of slapstick. And there were banjos were involved, presumably to enhance the overall comedic effect.

Basically, distasteful clowns with banjos as a comedic prop.

When I started getting into clawhammer style banjo, my impression was refined at least a bit. Turns out that the performers were actually using the same fundamental downstroking technique I was, and were even partly responsible for popularizing it.

Yet, when I first heard musician, banjo historian and expert-on-all-things-minstrel Greg Adams play a few minstrel era tunes in concert a few years ago, I was still entirely ill-prepared for what came out of his banjo.

In swift order, that caricature of the minstrel performers being little more than 19th century banjo-wielding prop comics was summarily annihilated.

The tune he played that really did it for me, that made it impossible to hold onto my old vision of minstrelsy, was “The Japanese Grand March,” our tune of the week.

It was originally published in “Buckley’s New Banjo Book” in 1860, and reportedly composed to honor Japan’s first ever diplomatic mission to the U.S., which occurred in that year (the background image in the video is of the USS Powhatan, the ship that carried the Japanese delegation across the Pacific).

As you can hear for yourself, this is not “banjo as an afterthought” kind of music. From both a technical and compositional standpoint, there’s a high level of musicianship here (Brainjo level 4, for Pete’s sake!). The minstrel performers clearly took their music – and their banjos – quite seriously.

Translation: these guys were good.

These were not clowns using banjos as a punchline.

Greg’s performance of this week’s tune (and his infectious enthusiasm for this music) led me to begin my own exploration of the music, to replace the broadly stroked image of minstrelsy I’d had in mind with one far more nuanced and detailed. As I discovered, there’s much more to this story than meets the eye. Though that’s almost always the case, isn’t it?

Of course, any type of exploration of minstrelsy requires one to confront all that goes with it, including the unabashed racism that was endemic in that period of American history. There’s much of this part of our history that we’d like to forget.

But forgetting would require throwing the baby out with the bathwater. And there’s a very large baby here, which is the music.

Spirited, sublime music. A substantial body of work whose contribution to the story of the banjo and the evolution of American music is far too large to be ignored. In other words, there are parts of the minstrel legacy that are definitely worth remembering.

And for the clawhammer banjo player, there’s also much to be learned. There are the tunes themselves. And then there are also all the inventive ways the minstrel performers employed the downstroking technique – ways that produced all sorts of cool sounds and rhythms.

The tunes provide a great technical workout, as well as an opportunity to add to your downstroking bag of tricks. Plus, you can’t help but come away with an expanded appreciation of what’s possible with clawhammer style.

Just this one particular tune, even, provides all of that.

(The banjo I’m playing is one I just acquired (part of why I chose this tune for this week!), a “Boucher” style replica by Jim Hartel, who’s renowned for his work making the banjos of this era. It’s an outstanding instrument. )

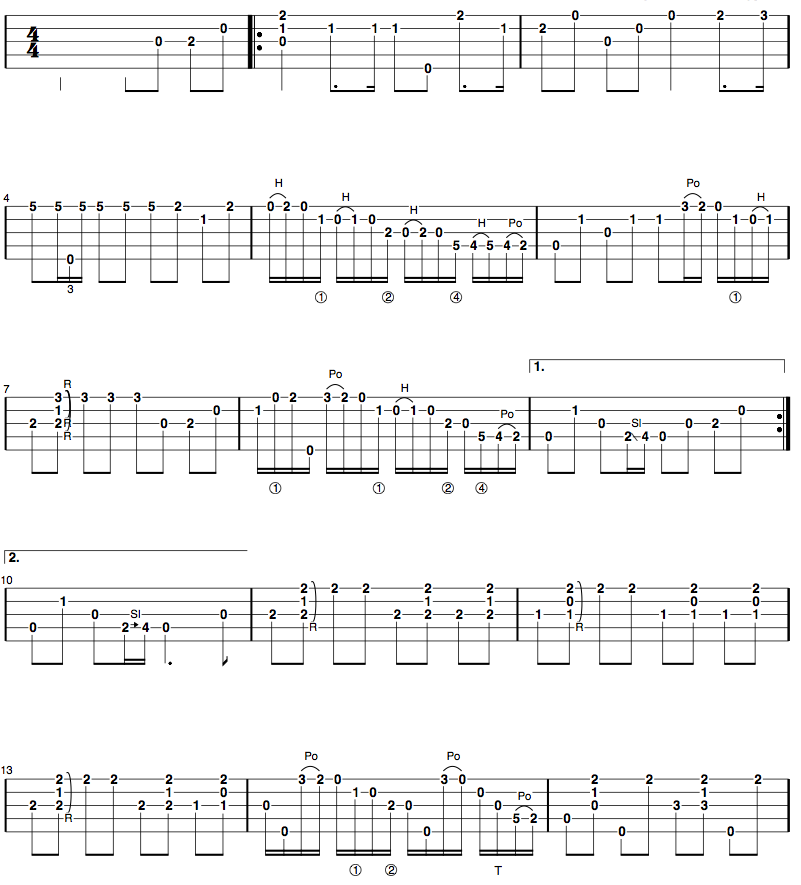

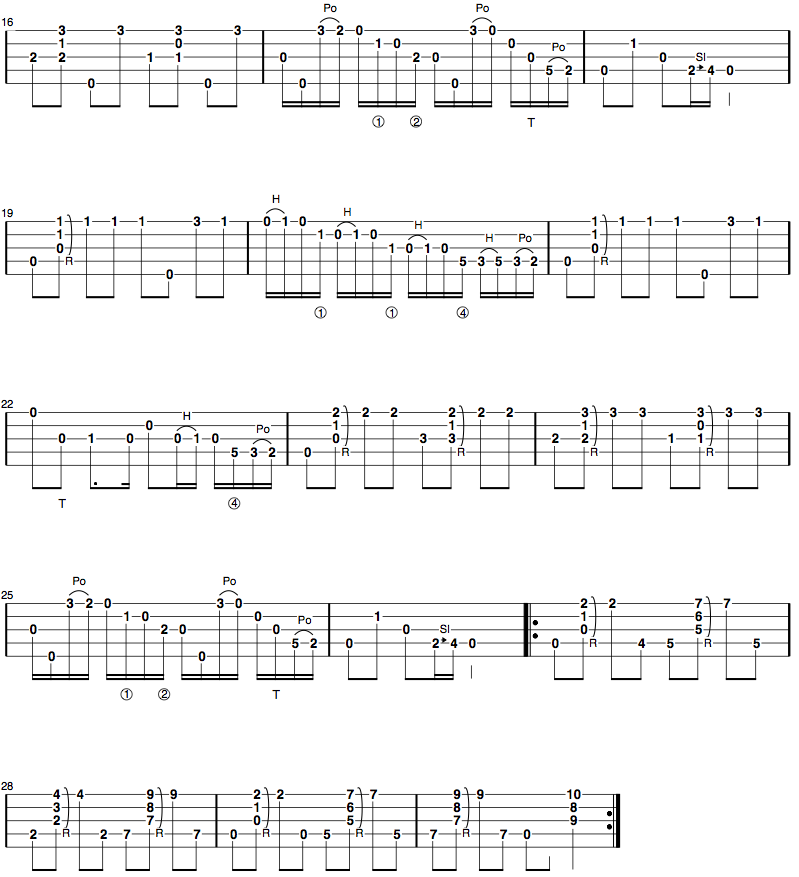

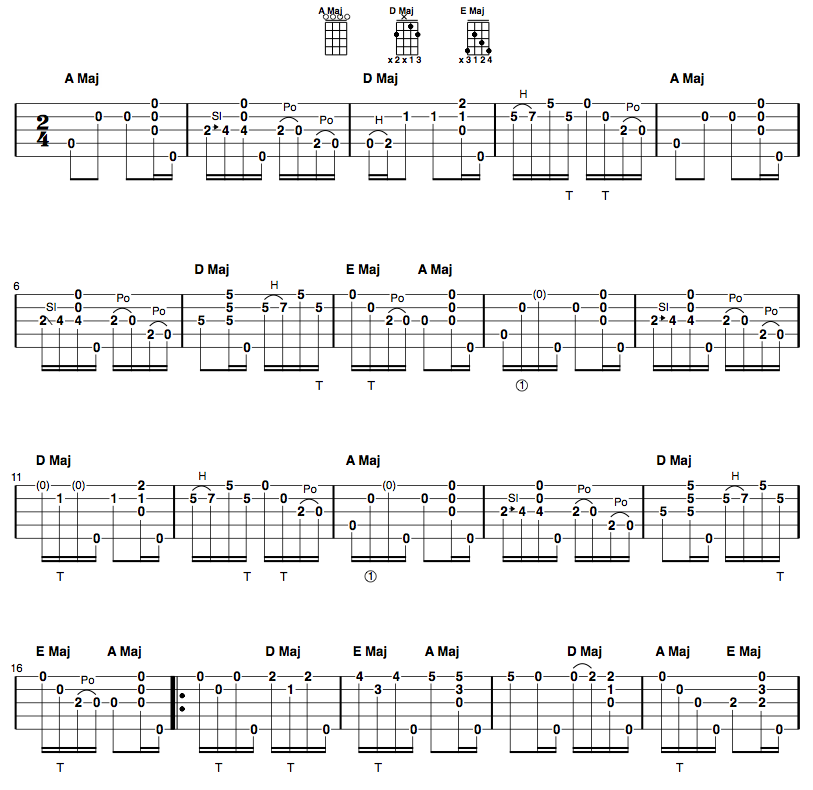

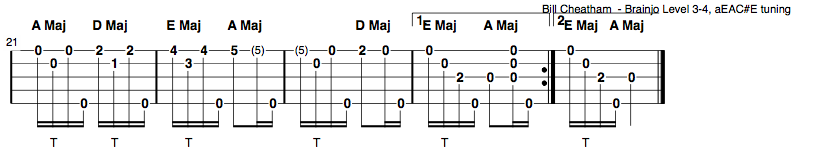

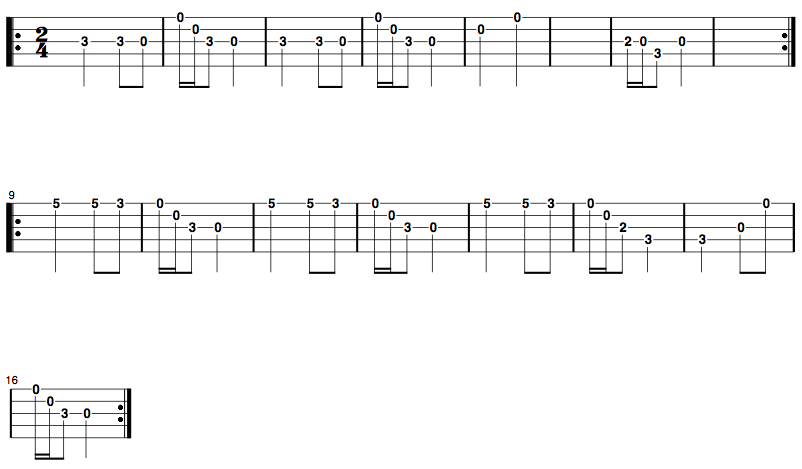

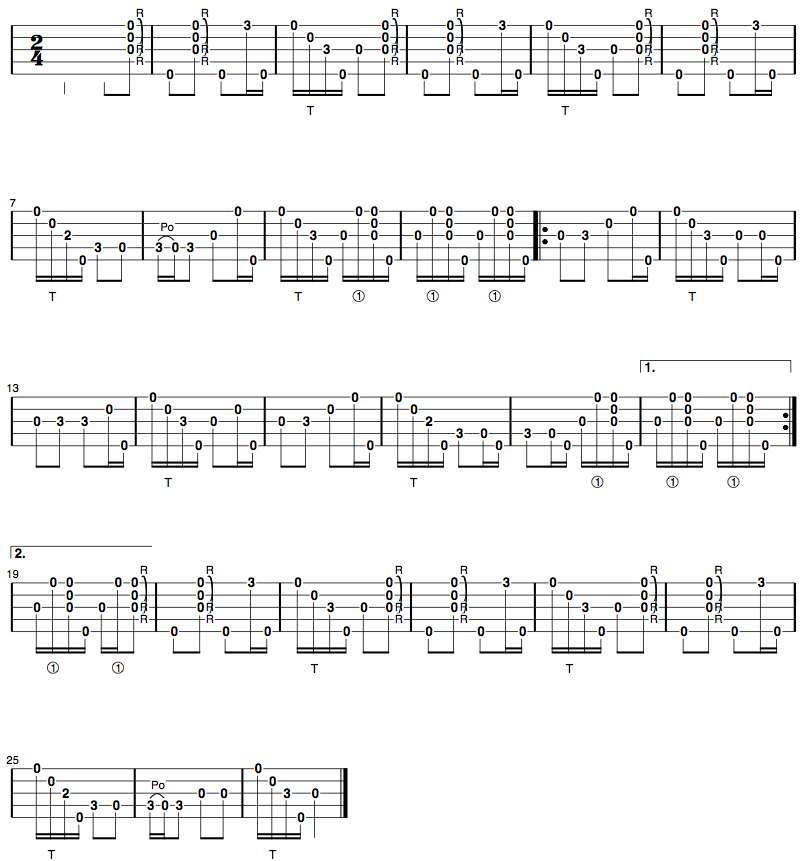

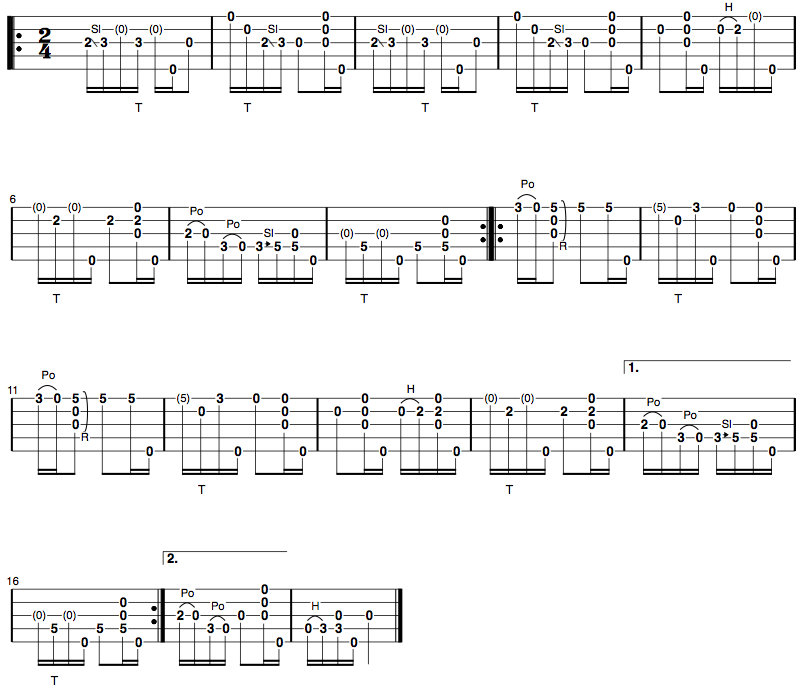

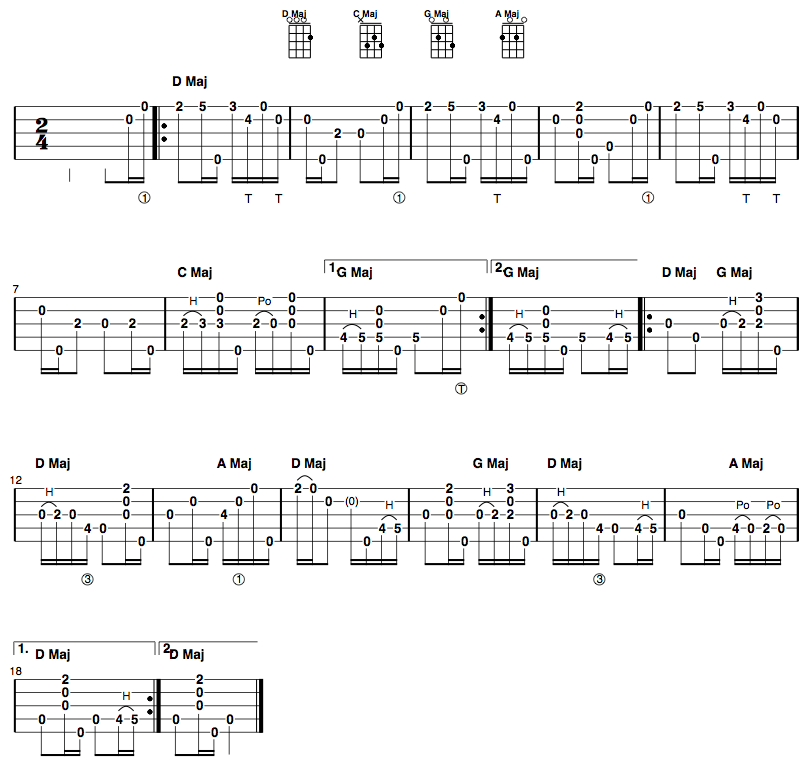

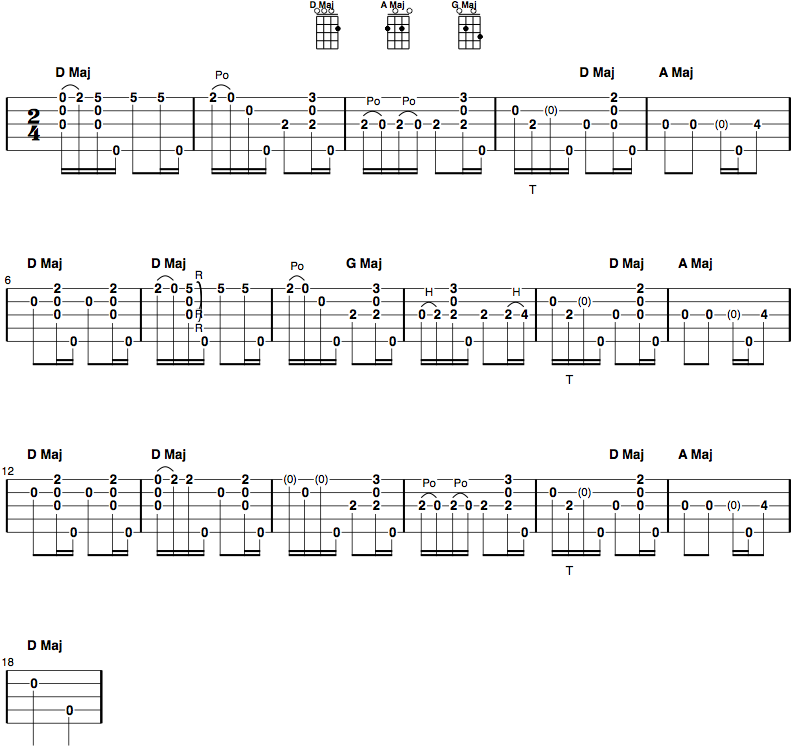

The Japanese Grand March

bEAD#F# tuning (“gCGBD” equivalent), Brainjo Level 4

Notes on the tab:

I’m playing this piece in a lower tuning to suit the longer scale of the minstrel banjo. To play this on a modern, steel-strung banjo, simply tune to gCGBD.

Probably the most challenging parts of this tune are those descending run down the strings, first appearing in the 5th measure. How I play these depends on the particular banjo I’m playing. If it’s a banjo that’s very responsive (louder, modern, steel strung banjo), then I’ll usually use alternate string hammer-ons to generate the fretted notes that are played on a string lower in pitch than the one that’s been previously struck. For a less responsive banjo (where those hammer ons may not be audible enough), I’ll use a drop thumb instead.

For more on how to read banjo tabs, check out my complete guide on reading banjo tabs.