One of the great things about old time music is that, while it exists within a cultural tradition, its rules are flexible.

Take the classic fiddle tune. Technically, a fiddle tune is an instrumental. It’s right there in the name, after all.

But when you’re locked into a really good fiddle tune, it feels great. And in those moments of high emotion, sometimes you just want to sing.

Yet, if you’re sitting first chair violin in the London Philharmonic performing Mahler’s 3rd symphony and decide to improvise a verse, you may soon find yourself jobless. In that tradition, there’s ONE way of doing things, and departures, well intentioned or not, are not tolerated.

But in old time, you’re free to let it rip. Such spontaneous emotional emissions aren’t only expected, they’re welcomed. In fact, getting yourself to a state in which you feel so inclined is kind of the point.

And so, even though most “fiddle tunes” don’t technically have words, that hasn’t stopped musicians from adding them.

Over time, different tunes have come to be associated with different sets of words. And you’ll find certain verses recur in multiple tunes, dubbed “floating verses” due to their tendency to “float” from one tune to the next. These are Swiss army knives of old time lyrics, providing easy access to something to sing when the mood strikes you.

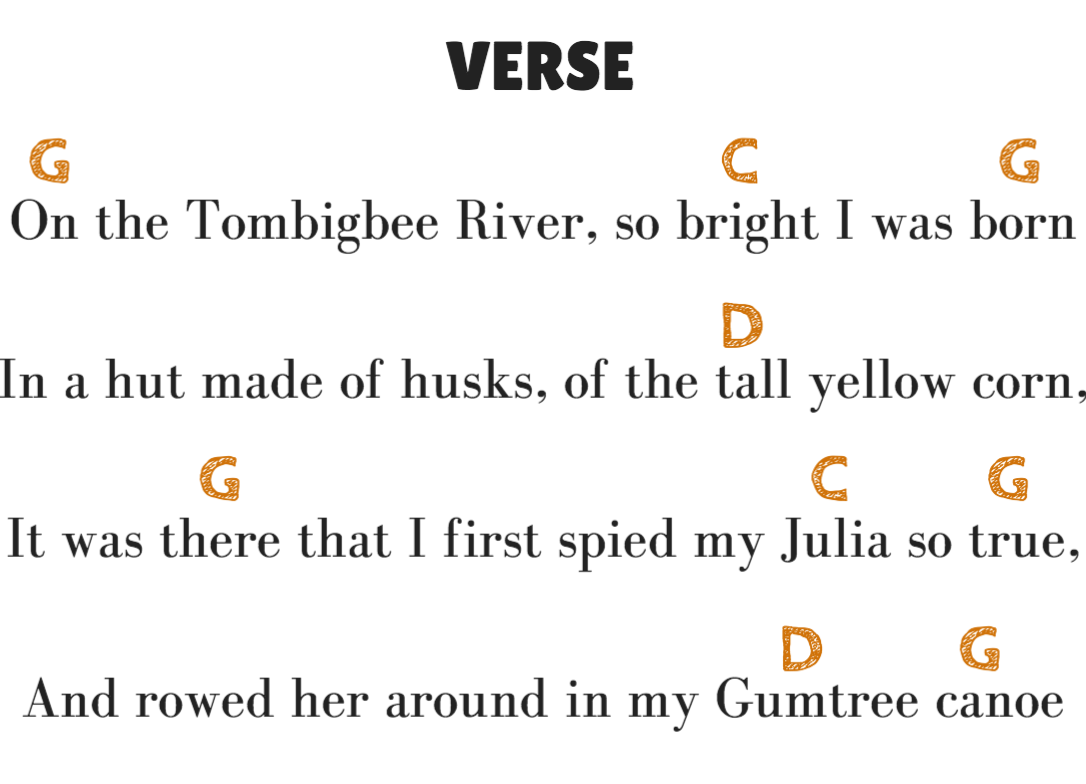

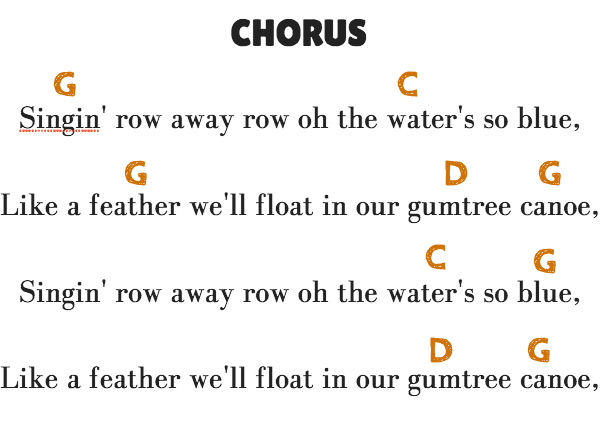

Sometimes things go in reverse, as was the case with this week’s tune of the week, Sourwood Mountain. It began its life as a song, with words integrated at the moment of conception.

Somewhere along the way a fiddler liked it so much he or she decided it must be sawed. And from there it took on a second life as a “fiddle tune.”

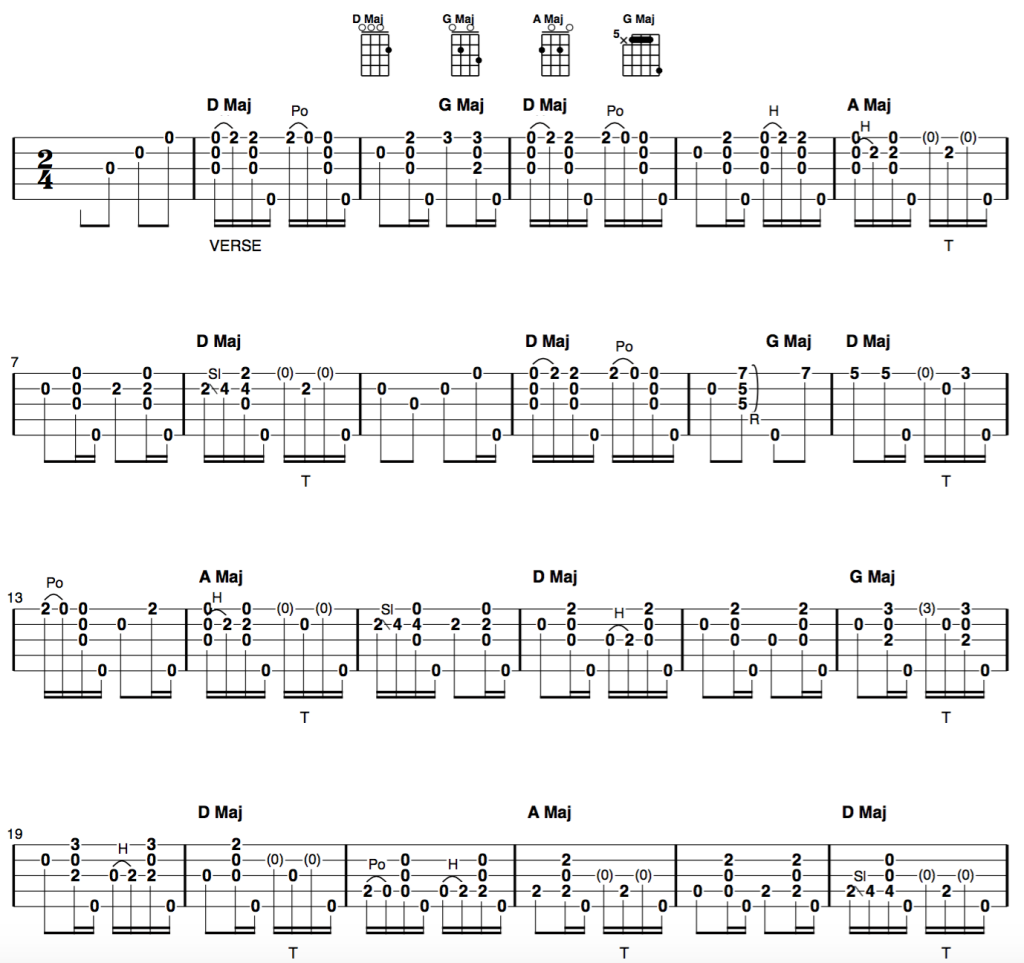

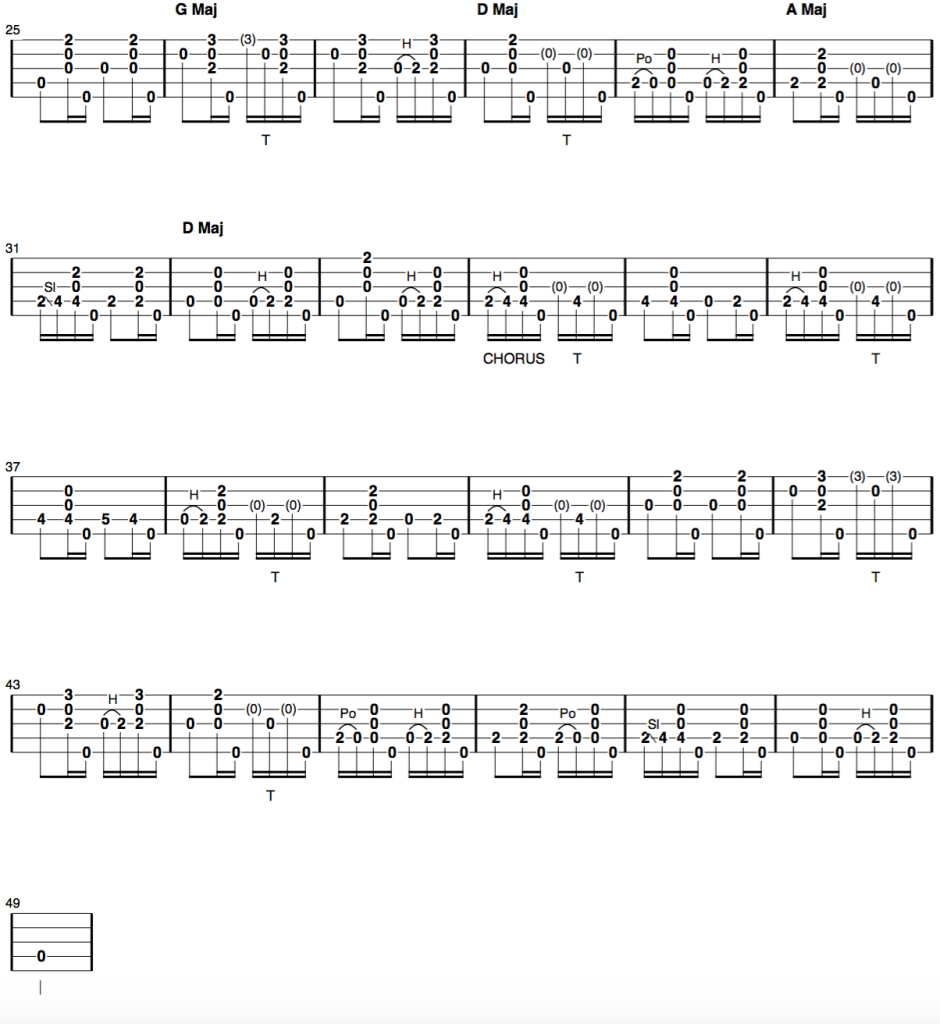

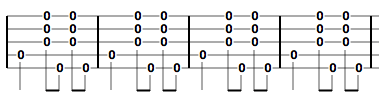

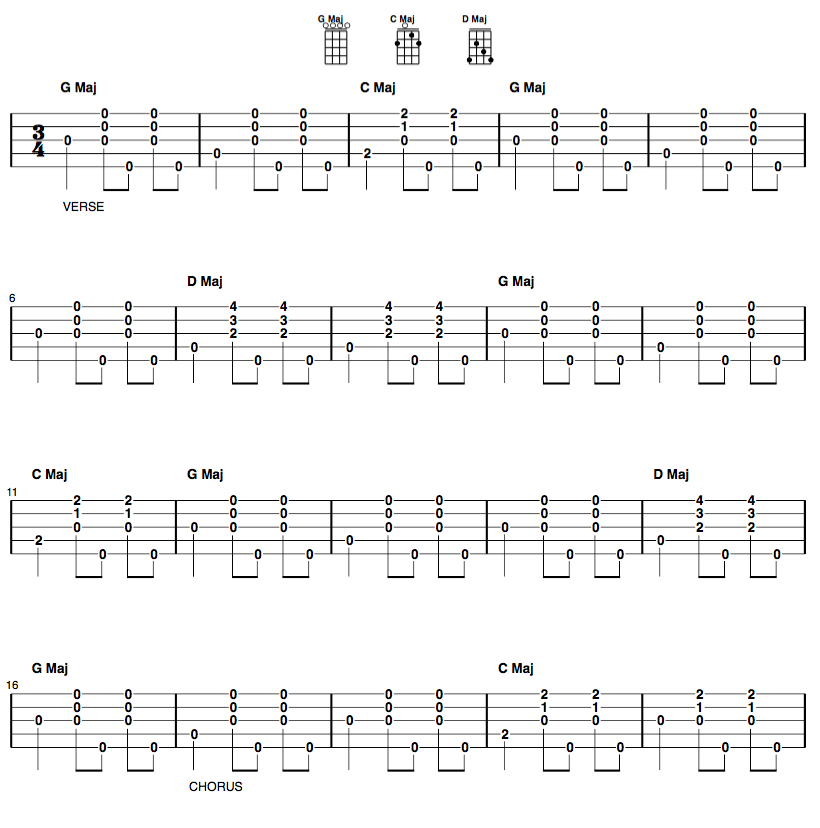

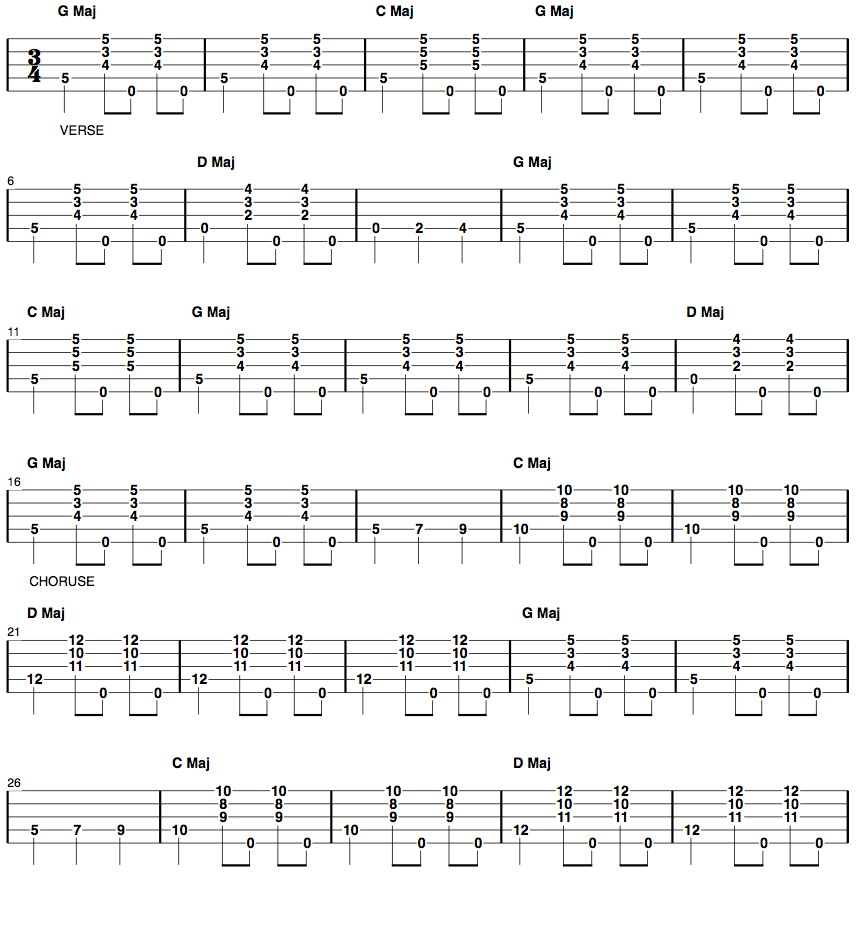

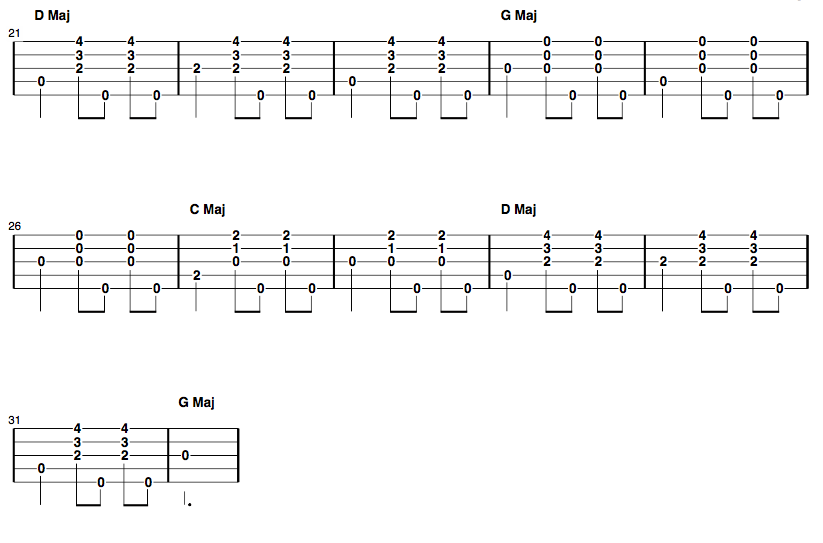

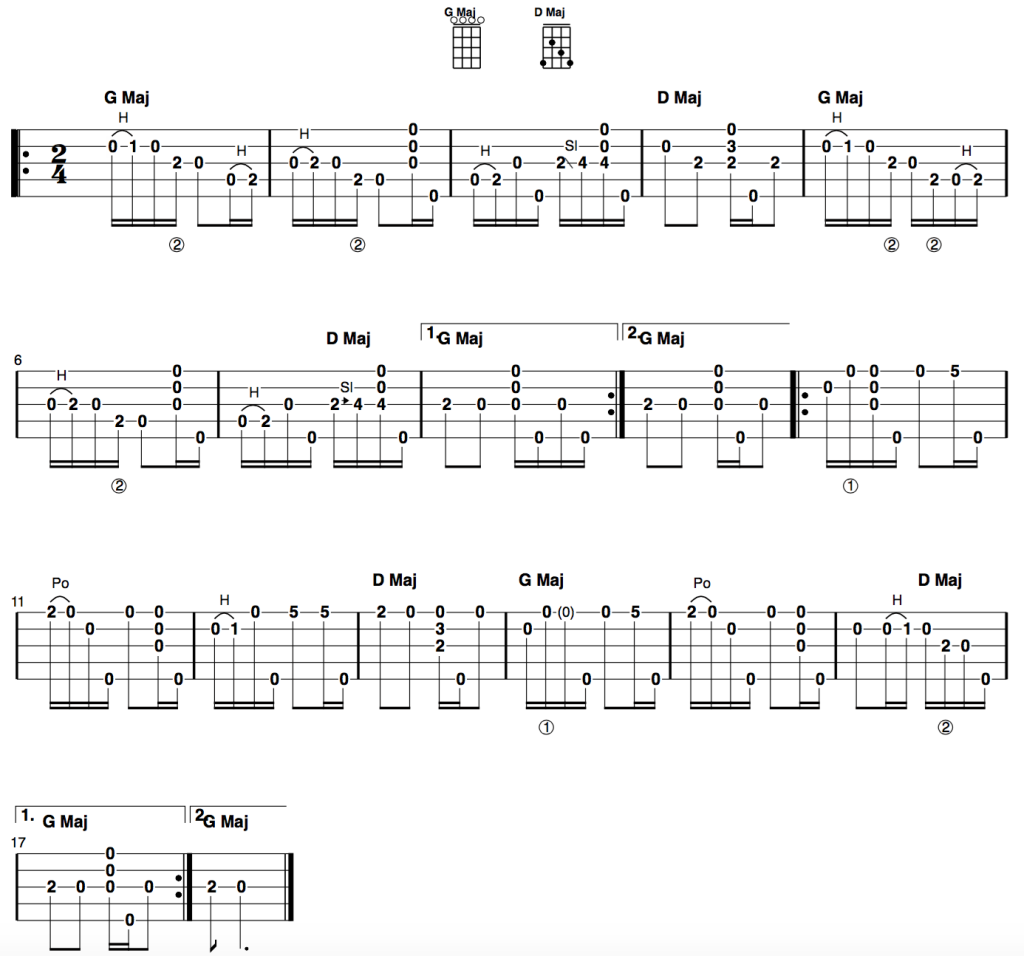

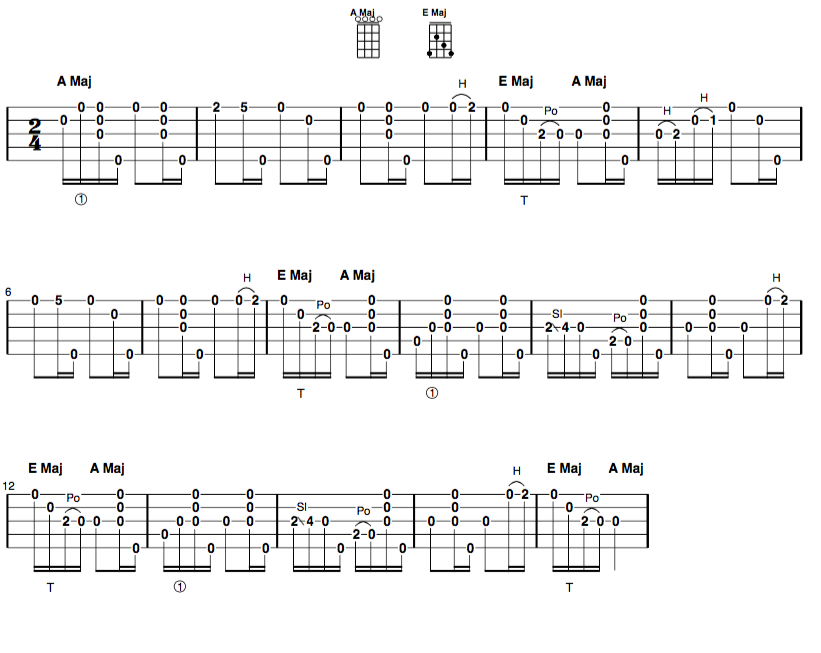

Sourwood Mountain

aEAC#E tuning, Brainjo level 3

Notes on the tab:

Notes in parentheses are “skip” notes. To learn more about these, check out my video lesson on the subject.

For more on reading tabs in general, check out this complete guide to reading banjo tabs.

Level 2 arrangements and video demos for the Tune (and Song!) of the Week tunes are now available as part of the Breakthrough Banjo course. Learn more about it here.

View the Brainjo Course Catalog