There’s something special about folks who play banjo.

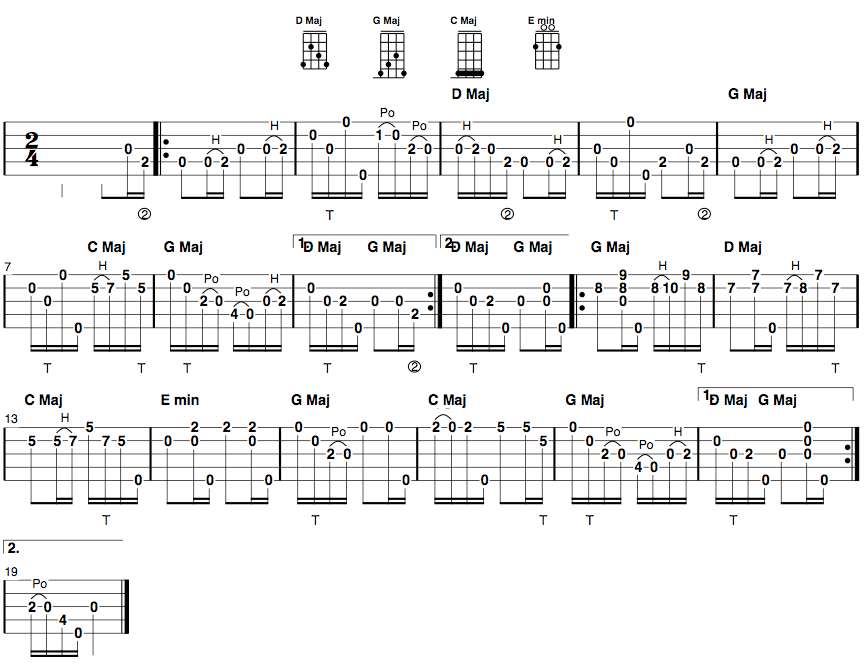

As some of you know, at the end of December I offered the 12 Days of Banjo songbook at “pay what you want” pricing through the end of the year. Anyone who wanted the book could download it with a contribution of their choosing (including for free).

I mentioned then that the “12 Days” was also part of our family’s holiday fundraising project, and so we would be directing half of any proceeds to charitable organizations of my kids’ choosing.

I was blown away by the subsequent response. But, truth be told, not totally surprised.

For whatever reason (though I have my own pet theories), folks who decide to pick up the banjo are some of the most humble, self effacing, compassionate, and generous people on the planet. In fact, I defy anyone to find a more good natured group of individuals who share a common interest. This also happens to be the thing I love most about banjo camps, the great music notwithstanding.

So, I’m delighted to share with you that, thanks to that generosity of banjo pickers the world over, we were able to make a total donation of $720. My daughter Jules is directing her portion to the Atlanta Humane Society, and my son Tucker to the Atlanta Food Bank (see their checks above).

As Jules says, “we both decided to help living things.”

So to every one of you who contributed, thank you. Like I said, there’s something special about folks who play banjo.