Episode 24: Banjo Lessons From Steve Martin

– Steve Martin

I think you’d be hard pressed to name a celebrity more beloved than Steve Martin. More than an “A lister,” he’s one of those people you can’t imagine a world without (nor would you want to!). In fact, I hope he outlives me.

And there’s seemingly no end to the things he does really, really well.

A master actor, entertainer, magician, writer, storyteller, songwriter, comedian, and – last but certainly not least – banjo player, he’s clearly one of the most talented humans walking atop our spinning blue rock.

Yet, he claims to have “no talent.”

Readers of this series know that I would agree. Because what he means by this is that he wasn’t born with the skills needed to become great at all of those things, he acquired them. He got good at a lot of things because he’s good at getting good at things.

I recently had the pleasure of listening to his memoir “Born Standing Up,” which recounts the early days of his career as a stand up comedian. In addition to being entertaining, funny, and, at times, poignant, it’s also an illuminating look at why he’s so good at getting good.

And while the book contains no banjo instruction, it is nonetheless rich with lessons that are applicable to anyone trying to learn to do anything well, including banjo pickery.

LESSON 1: Seek feedback relentlessly, and modify accordingly.

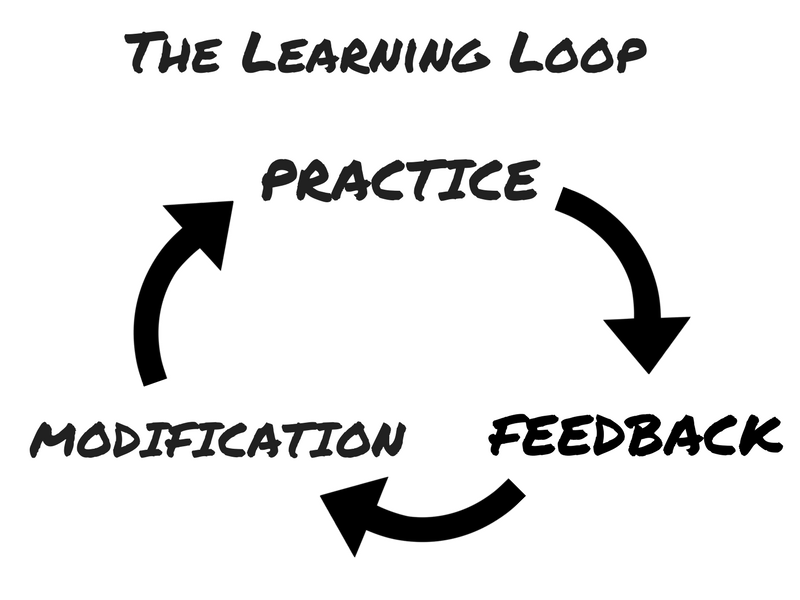

Feedback is essential to the learning process. In fact, the fundamental learning loop can be described as practice –> feedback → modification → practice → feedback…and so on.

Increase the frequency and quality of feedback, and you accelerate the learning loop. Positive or negative, feedback is always valuable information.

Yet, most folks are apprehensive about subjecting their abilities to public scrutiny, lest they risk an unfavorable reaction. For Martin, though, bombing on stage wasn’t viewed a personal failing, but a necessary and invaluable opportunity for growth.

And so he sought out time on stage whenever he could get it. His objective was never to show everyone how funny he was, but to find out how he was doing. Each session in front of an audience was an opportunity to collect data and get better, and learning was more important than praise.

Acquiring feedback is just the first step, however. The key is to then use that information to modify the thing you’re trying to learn.

Which is exactly what he did. Martin kept detailed records of every joke and gag, and how they landed with the audience. He’d then take the data from those performances and write out a plan for how to make his act better the next time.

Regardless of what you’re learning, treat the process as a scientist would. Every practice session or performance is an experiment, a chance to test your hypothesis, rather than a referendum on your self worth.

If the results indicate the hypothesis is incomplete or wrong, then it’s back to the lab to devise a new one. Learn to love this iterative process above all else, and continued progress is guaranteed.

LESSON 2: Seek out sources of inspiration, and study them in depth.

Martin cites many influences along his rode to mastery. During his time working at the Main Street Magic shop at Disneyland, for example, he was drawn to the act of Wally Boag, the headliner at Disney’s Golden Horseshoe Revue.

But his role models and mentors were more than just sources of entertainment and inspiration. They were the subjects of intense study. Martin meticulously analyzed and memorized the nuances of Boag’s routine, to the point where he could re-enact his act verbatim.

Nobody gets better in a vacuum, and I think its hard to overstate the value of seeking and studying the heroes you wish to emulate, especially in the formative stages of your journey. It’s no coincidence this is a theme in every master’s story.

For the banjo player, this means identifying the banjoists whose playing speaks to you most, and studying them. Study their music, study how they play, what they say, and how they learned.

LESSON 3: Believe you can become anything.

Perhaps the biggest learning lesson in the entire book, which is also the overriding theme in all of Brainjo, is that, thanks to a brain that continuously changes throughout your life, you can reprogram yourself into what you want to become.

[RELATED: Click here to learn more about the Brainjo Method, and the recently launched Breakthrough Banjo course for fingerstyle banjo.]

So getting good at the banjo, or anything else, has nothing to do with natural ability. That just determines where you start.

But getting good at the banjo has everything to do with HOW you learn, or how you go about reprogramming your brain. That’s what determines where you end up.

And this is why I loathe the concept of natural talent. Not just because it isn’t useful, but because it leads so many to never live out their full potential.

Without a firm belief in our capacity to continue to grow and improve, we’d never have the courage to pluck that first banjo string, or hop on stage for the first time.

Nor would we have the courage to soldier on in the face of negative feedback. If our abilities are fixed, then better to remain silent and be thought of as “funny” or “musical” than to perform and remove all doubt.

Had Steve Martin bought into the talent myth, we’d never seen the likes of Navin R. Johnson or Lucky Day.

We’d have never added the phrases “I’m a wild and crazy guy” or “excuuuuse me” to our collective vocabularies.

Our ears would’ve never been graced by the sounds of The Crow or Rare Bird Alert.

And in the 2nd grade, my friends and I could’ve never spent hours at McDonald’s rolling in stitches as we tried to perfect our timing of “the napkin trick.”

Had he bought into it, there’s no telling how many millions of hours of laughter and joy the world would’ve lost.

By the way, the book “Born Standing Up” is outstanding, and hopefully this post has whetted your appetite. The audio version is particularly excellent, as it is narrated by Martin, and contains his banjo playing interspersed throughout the recording.

By the way, the book “Born Standing Up” is outstanding, and hopefully this post has whetted your appetite. The audio version is particularly excellent, as it is narrated by Martin, and contains his banjo playing interspersed throughout the recording.