The Laws of Brainjo, Episode 5

How Much Should You Practice?

If you hang out around banjo forums for long, you’ll notice certain commonly recurring topics:

“What’s the best banjo under X amount of dollars?”

“Can I play Scruggs style without fingerpicks?”

“How much do you practice each day?”

Years ago when I first took up the banjo, I’d find those conversations about practice time a bit demoralizing.

Tales of daily marathon sessions of 8-10 hours were commonplace. Anything less than 4 and you best not speak up for fear of public shaming.

I was in my first year of medical residency when I got my first banjo, when 90 hour work weeks were the norm. In those days, I was thrilled if I could squeeze in 15-30 mins of picking time in a day. Was I deluding myself by thinking I could become a banjo player with such comparatively little time to devote to it?

Needless to say, not only did I become very interested in methods that would maximize practice efficiency at that point, but I also became intensely concerned with the question of how much practice was truly enough.

We seem to have a natural tendency to believe that if a little of something is a good thing, a lot is even greater, even if our experience tells us that more is often not better.

So what then of practice? How much is enough? And is there such a thing as too much?

The Minimum Effective Dose

First, let’s clarify precisely the question we’re asking, which is how much practice time is necessary to get results? In other words, what amount of time is required to make sure that the next time we pick up our banjo, we’re a better player?

Remember, the goal of each practice session is not to get better right then and there, as getting better requires structural and physiological changes in the brain that take time – changes that are set in motion during practice, but that continue long after we’ve set our banjos down (much of it while we sleep).

With this in mind, our question then becomes, what’s the minimum amount of time needed to signal our brain to change?

Necessary Conditions

As stated above, to learn anything, the brain must literally remodel itself to build novel neural circuitry that supports the new skill or technique we’re learning.

Yet, we don’t have unlimited space or energy to work with. Our brain is relatively fixed in size, and building new brain stuff requires precious energy stores. To operate successfully within these constraints, our brain must be selective about when it changes, and when it doesn’t.

To illustrate, think back to February 9th of this year. Do you remember what you had for breakfast, lunch, and dinner? Do you remember who all you spoke with that day, and the contents of those conversations? The emails you sent? The websites you visited?

Me neither!

You don’t remember those things because your brain didn’t deem them worthy of long term storage. They weren’t worth spending valuable space and energy on. I think you’ll probably agree that your brain made a good decision. Whether it was eggs, toast, or a pop tart on February 9th, who really cares?

And how exactly did your brain decide not to encode those things into long term storage?

Because you didn’t pay much attention to them.

Every minute of every day, our brain is busy sifting through an incomprehensible amount of sensory data. Most of it is discarded as irrelevant, not worthy of the resources required to store them for a later day.

But what of the stuff that is worthy and relevant? How does the brain know to keep that for later?

By only storing the things you were paying close attention to.

Attention is the means by which we tag the events of the day to signal our brain that we might need them again later, cueing the brain to then rewire itself towards that end. There’s a large body of research on this issue, and the results are solid: without attention, memories aren’t formed and skills aren’t learned.

But the type of sustained and focused attention we’re talking about here isn’t easy, and it isn’t something most folks can carry on for too long in one stretch. At least not before the mind tires and begins to wander. And once the mind wanders, further efforts are wasted.

So what’s the typical amount of time a person can maintain this level of focus? About 20 to 25 minutes.

Until recently, we were left to only make an educated guess about this question. But thanks to recent technological advances, we now have the tools to assess when the brain has remodeled itself through practice, enabling researchers to target questions of this nature more precisely.

Using those tools, it’s been shown that 25 to 30 minutes of focused practice time is enough to produce the structural changes in the brain that support skill acquisition.

Putting all this together, we can reasonably conclude that, when learning something new, about 20 to 25 minutes of focused practice is sufficient for achieving our goal, which is to ensure that the next time we sit down to play the banjo, we’re a better player.

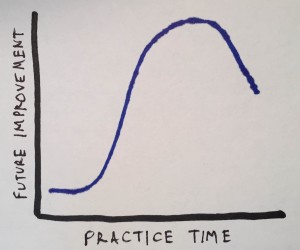

Furthermore, given what we know of the limits of human attention, and given that there’s a limit to how much the brain can change in a day, the practice curve is likely U shaped, like this:

After a certain amount of time, we face diminishing returns, as our attention wanes and we run the risk of spinning our wheels. This goes on too long and we start to compromise the quality of our inputs. We can take a break and return later, of course, but at some point we come up against the limits of neuroplasticity.

So, should your predicament be as mine was many years ago, when the demands of work and family left little time for banjo plucking, don’t despair. Take heart, and keep mind this next law of Brainjo:

Episode 6: When Should You Practice?

Back to the “Laws of Brainjo” Table of Contents