Episode One: The First Law

10,000 hours.

You may have heard mention of this before.

Popularized in Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers”, it’s the average number of hours across disciplines that research shows it takes to become an expert. The average amount of time it takes to master something.

The take home message from the 10,000 hours concept is that, despite the stories we share as part of our cultural mythology, passion and dedication are the key determinants of mastery. From sculpting to picking, humans get really, really good at stuff through hard work, not through some fortuitous genetic gift of talent.

Now, you can read this two ways.

On the one hand, this is a very encouraging notion, as it means that when it comes to your banjo playing goals, virtually anything is possible. With consistent, focused effort, the sky is the limit.

On the other hand, 10,000 hours is nothing to sneeze at. If you can manage 2 hours of picking every day, then you’ll reach your musical Shangri-La in roughly 13 years, 8 months. To someone picking their first note on the 5 string, those kind of numbers might be a little discouraging.

But there’s more to this story.

Specifically, there are a few very important points that are usually overlooked in the “10,000 hours” discussion.

1. Even more important than how much we practice is how we practice.

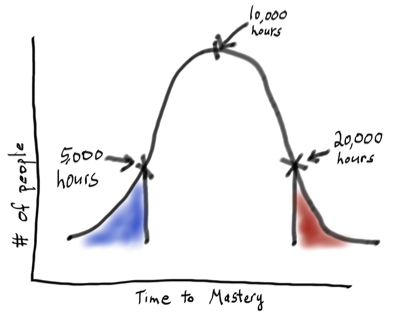

10,000 hours is an average. If we were to take all the data points and plot them out, we’d get a bell shaped distribution, with the apex of our bell at the 10,000 hour mark. Something like this:

So some folks in this data set have spent a good bit more than 10,000 hours to achieve mastery.

And some have spent a good bit less.

Wouldn’t it be nice to end up on the front end of the distribution, amongst the 5,000 hour crowd (the blue shaded area), not the 20,000 (in the red)?

If some folks can get there in 5,000 hours, there’s no reason to believe anyone can’t do the same. The rate limiting factor here, the primary constraint on the learning process, is the pace at which the brain changes. And that pace is largely defined by our biology – in other words, in properties of our nervous system that are common to all of us.

Those who reached mastery faster were just better at changing their brains. They practiced more effectively, in a manner that fully capitalized on the biological mechanisms that support learning.

2. Most people give up.

Most folks who set about to master anything, musical instruments included, ultimately end up giving up. There are surely more 5 strings collecting dust in closets and attics than being picked lovingly every day by skilled pickers.

And why do the majority give up? If mastery is just about putting in the hours, is it just because they’re lazy?

No.

They don’t give up because of a character flaw. They give up because they stop getting better. Research tells us that the single greatest motivator for learning is progress. Progress is the reward that keeps folks coming back for more. On the flip side, nobody plods on for very long in the face of no progress.

And what causes folks to stop progressing? Ineffective practice.

In this age of information, we are blessed with an overabundance of learning materials. It’s simple to find what we should be learning.

But how we should go about learning that material is seldom, if ever, addressed specifically. In spite of the fact that it’s the single biggest determinant of success or failure, how to practice is rarely considered or communicated.

That needs to change.

3. The greatest proportion of improvements occur early in the learning process.

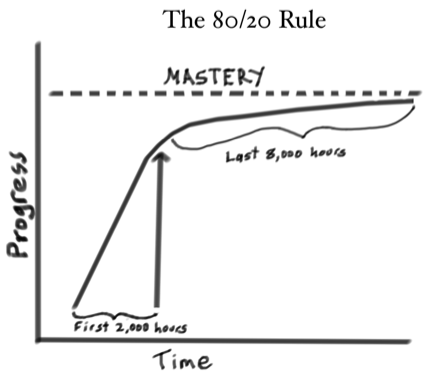

This concept, which applies to all sorts of various phenomenon, is often referred to as the “80/20 rule” (or the “Pareto Principle”, after the economist who first suggested it).

In this particular instance, the 80/20 rule states that 80% of your results are achieved through 20% of your efforts. In other words, provided that we’re mindful of our learning process, and that we correctly identify what that 20% is, we can achieve most of our gains in those first 2,000 hours. After that, we start facing diminishing returns on our time investment. The final stages of mastery, which take up a disproportionate amount of time, are about putting in long hours for gains that are often imperceptible to the casual observer.

If we plot this concept out graphically, it looks like this:

The First Law of Brainjo

Without a doubt, mastering any skill, including the banjo, requires focused, consistent effort. That said, 10,000 hours of any-old practice won’t magically get us where we want to go. Masters don’t become masters through the sheer force of will alone. It’s a necessary but not sufficient condition.

Masters become masters because somehow – be it luck, a great mentor, or natural disposition – they’ve managed to unlock the right process for learning. A process that leads to consistent, rewarding progress.

Replicate this process, and you too can enjoy similar results. Which brings us to the first law of brainjo:

To learn to

play like the masters,

you must

learn to play

like the masters.

Unlocking the secrets of and maximizing the brain’s capacity for growth and change has been an intense area of personal and professional interest of mine for two decades now (I’ve written about some of these principles in the “Your Brain on Banjo” article series for the Banjo Newsletter).

In the upcoming articles in this series, we will continue to extract insights from the fields of learning, mastery, and neuroplasticity to build a set of maxims for effective practice, and in so doing create a roadmap for helping us to mold the best banjo playing brain we can.

Go To Episode 2: How to Play “In the Zone”

Dr. Josh Turknett is the creator of the Brainjo Method, the first music teaching system to incorporate the science of learning and neuroplasticity and specifically target the adult learner