Not too long ago I was working on my computer with headphones on, running through one of my Spotify playlists. The playlist included an album from Ola Belle Reed that I’d recently added, entitled “Rising Sun Melodies”.

As track 4 rolled around, somewhere in recesses of my subconscious, while I was busily attending to some other business on the computer, I recognized that Bonaparte’s Retreat was now being played. It began with a stirring rendering on the dulcimer. My defenseless foot began dutifully tapping along.

But then, something unexpected. Something that broke my focus from the task at hand and redirected all of it to Ola Belle.

Ola Belle was singing.

Now, I’d heard Bonaparte’s Retreat a great many times from a great many folks up to this point. It’s one of the most classic pieces in the old-time music pantheon, and one of those tunes that virtually every musician puts their own personal stamp on. I imagine you could identify most any fiddler by the version of Bonaparte’s Retreat they play, in fact. And a risky tune to bring up in a jam for this reason, as odds are slim that my preferred Bonaparte is the same as your preferred Bonaparte.

But none of those versions had ever included any singing.

Personally, I’m always looking for an opportunity to add my voice to a tune. When I hear a great melody, I’m moved to sing along. So it’s always a joyous discovery when I find that somebody has already penned lyrics to a tune I’ve long enjoyed.

The lyrics she sings here are also delightfully self referential, as in it speaks of a fiddler playing the “Bonaparte’s Retreat.” I’m a sucker for self reference.

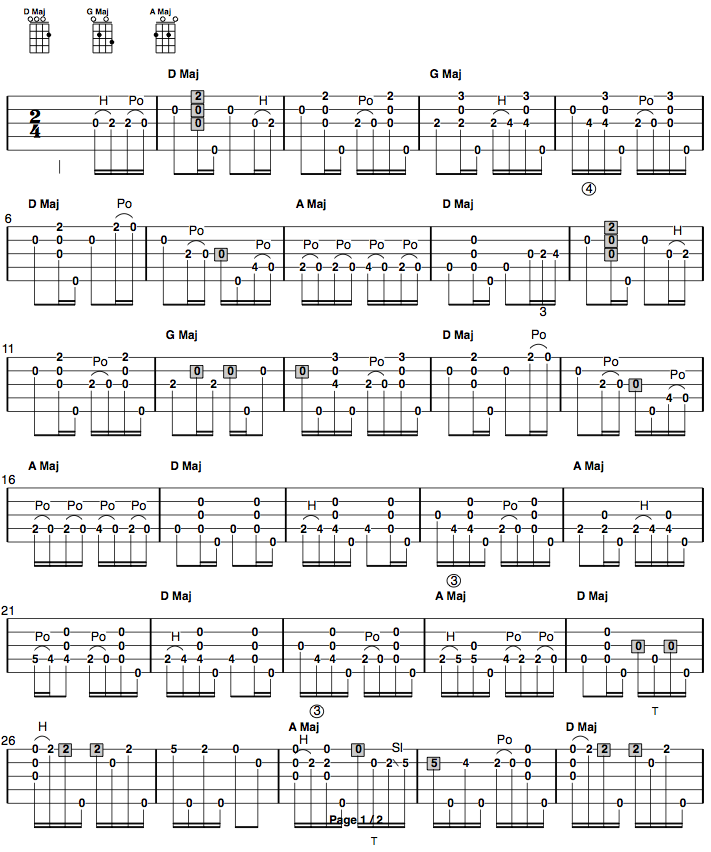

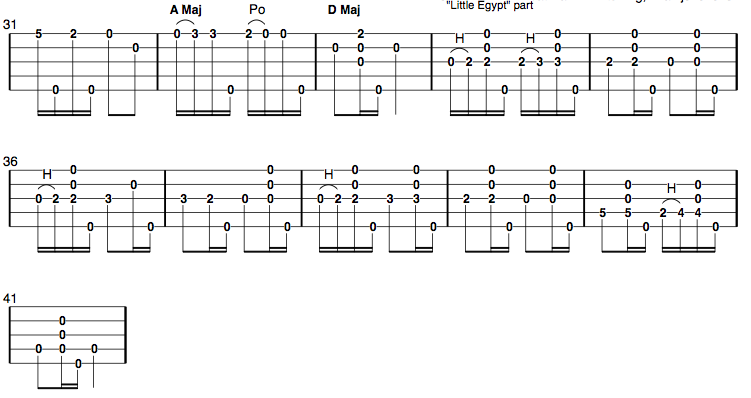

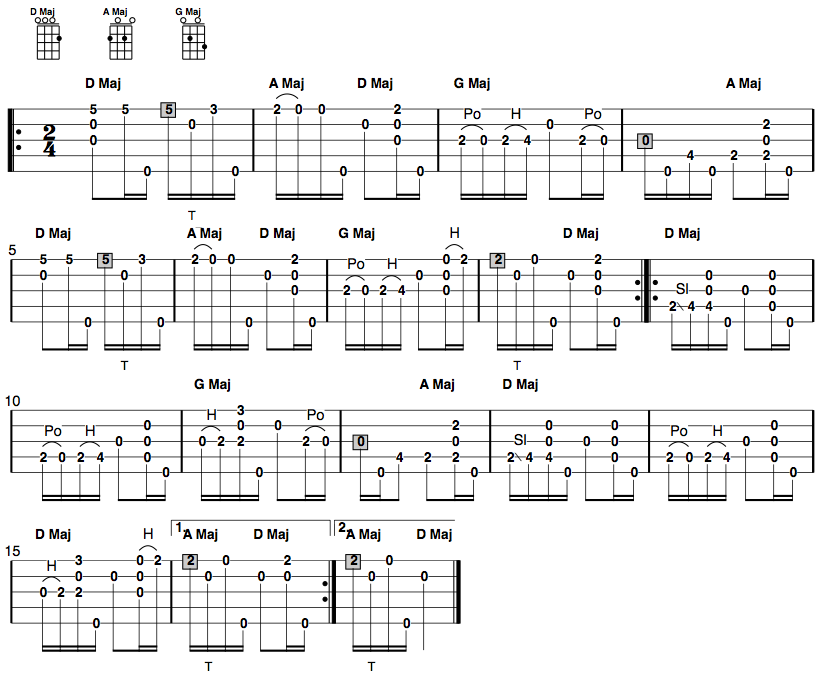

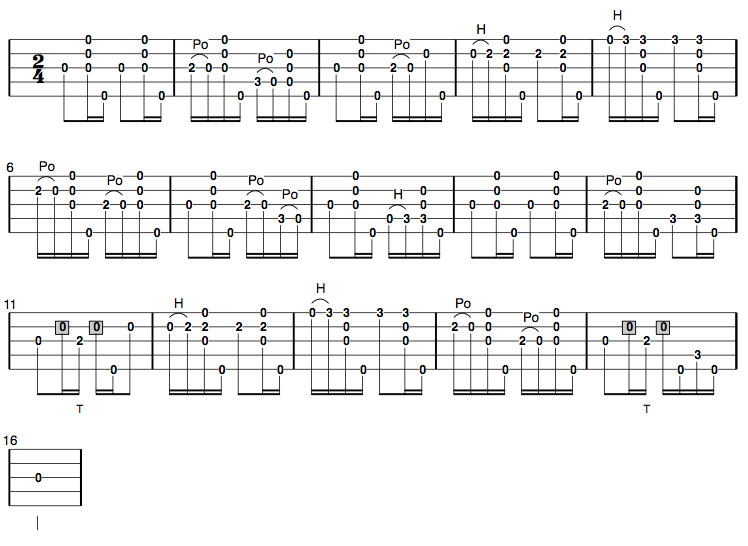

The next opportunity I had, I took out the gourd banjo and worked up yet another version of Bonaparte’s (this probably makes number 6), this one inspired by Ola Belle. For the moment, it’s become my favorite way to play it.