This week’s tune, while not technically a minstrel number, is of similar historical pedigree. Durang’s Hornpipe was first composed in the 18th century by Mr. Hoffmaster, a German violin teacher, for the famous hornpipe dancer John Durang.

What’s a hornpipe dance? Good question. Though we’ll never know the moves Mr. Durang became famous for, I imagine it looked something like this.

Fast forward 200+ years, and the tune is still going strong. That’s because it’s awesome.

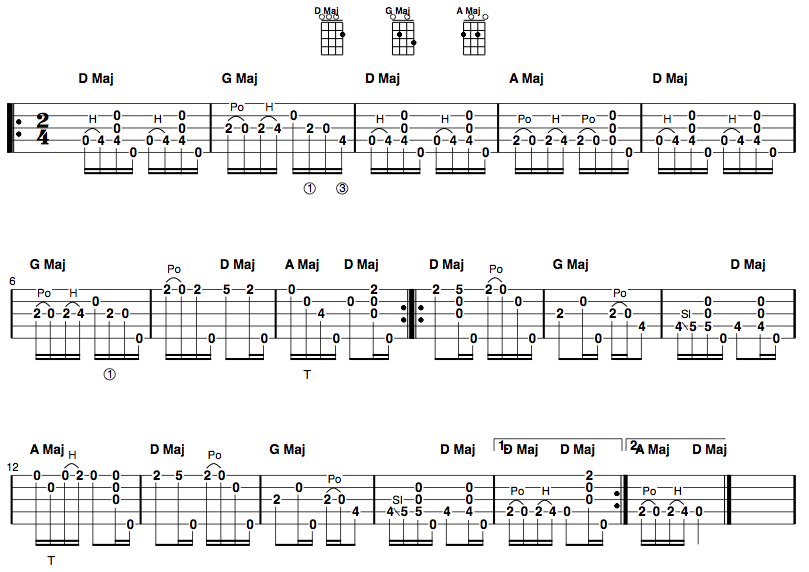

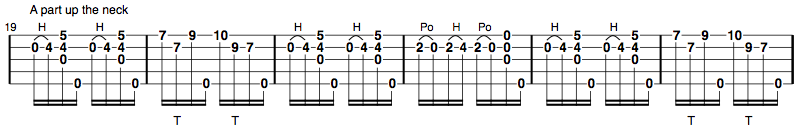

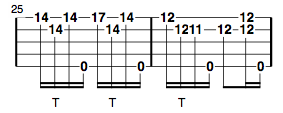

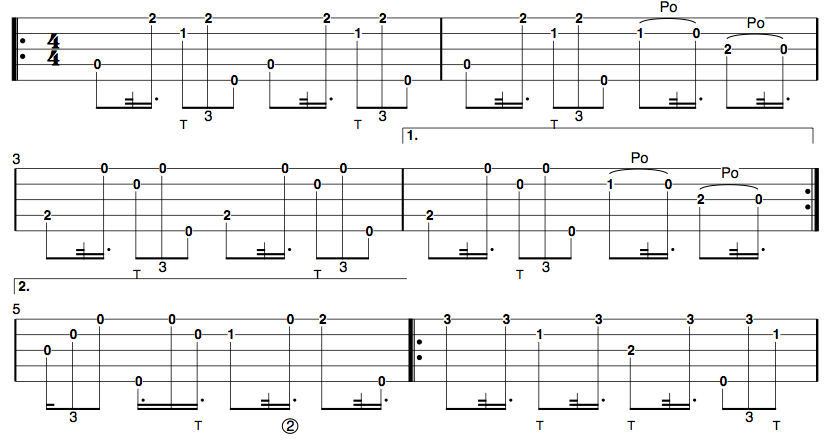

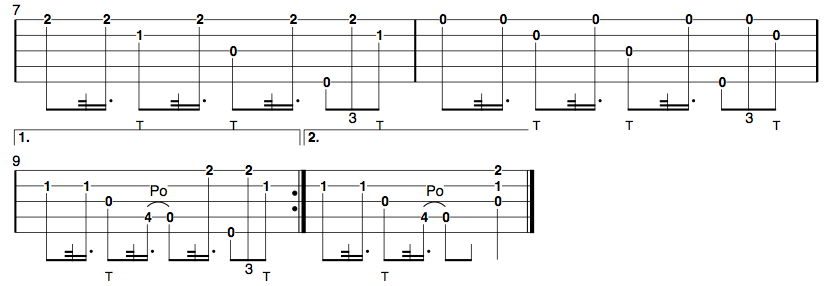

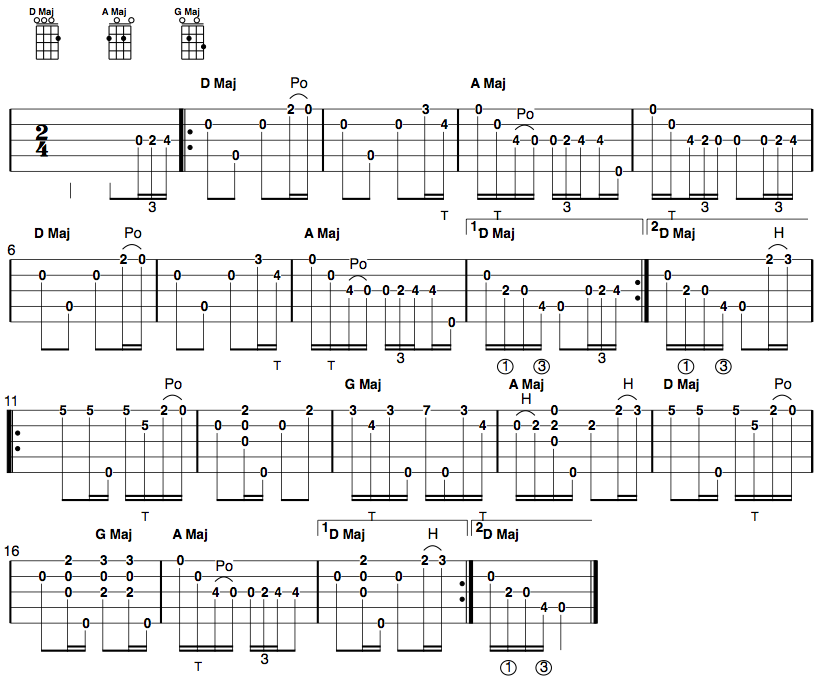

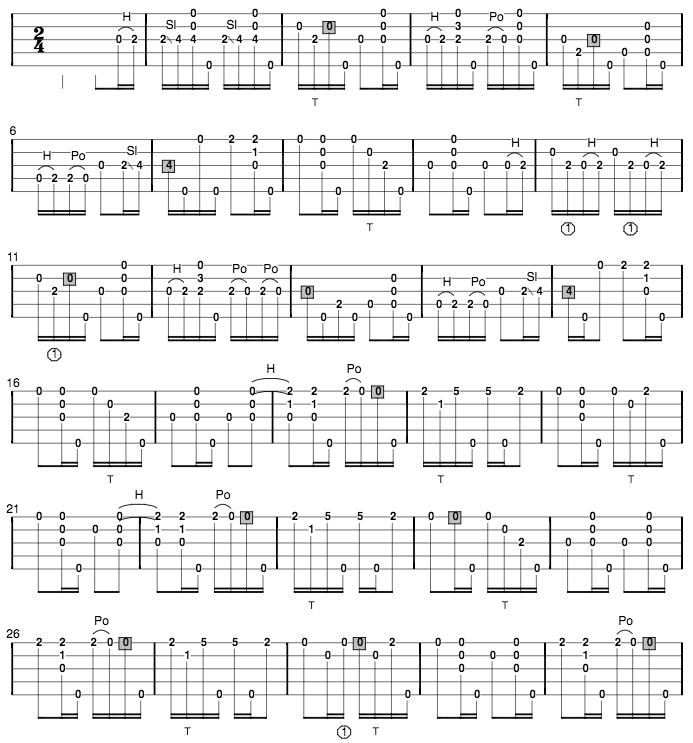

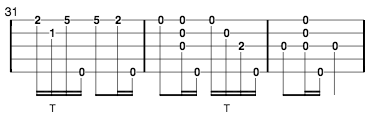

I’ve tabbed out both my main and optional “up the neck” variation (for the A part) below. The up the neck variation is a little trickier, hence the higher Brainjo level rating.

Durang’s Hornpipe

aDADE tuning, Brainjo level 3