We music lovers owe Thomas Edison a huge debt of gratitude. With his invention of the wax cylinder phonograph in 1877, he set in motion a chain of events that would ultimately culminate in the world we find ourselves in today. A world in which we have access to more music than we could listen to in a lifetime, through a device that fits into our pocket, no less. An embarrassment of riches.

We take the magic of recorded music for granted these days, but just imagine what it must have been like when this technology first burst on the scene. For the first time ever in the history of humankind, it was possible to take an audio snapshot of a moment in time. You could play your favorite music on demand, whenever you wanted.

And it all started with Edison’s phonographic cylinder.

Recently, Benjamin Canaday, a leading expert on the Edison phonograph and founder of Canaphonic Records, contacted me about helping him with a project. Benjamin, who is clearly carrying on Edison’s inventive spirit, has developed a process both for restoring wax cylinders back to their original condition and for using digital audio files to produce new cylinder recordings. Amazing and inspiring stuff.

And the project he wanted help with? To create new banjo recordings to transfer to original, restored wax cylinders.

It took me all of negative 8 seconds to say yes.

For the first tune in this series we chose “Johnny Comes Marching Home”, a Civil War era song popular around the time of those phonographs. It’s a melody that still remains popular today, having been re-packaged into the children’s song “The Ants Go Marching”.

I thought it’d be neat to demonstrate the difference in sound between the modern digital recording and the original wax cylinder recording medium. So you’ll note the transition from one to other mid-way through the video (here’s a link to the full recording on just the wax cylinder).

More wax cylinder banjo recordings are on the way. You can follow along as they come out on Benjamin’s youtube channel. And, if you should find yourself fortunate enough to own an original Edison phonographic cylinder, you can purchase your very own copy of this tune on ebay!

When Johnny Comes Marching Home

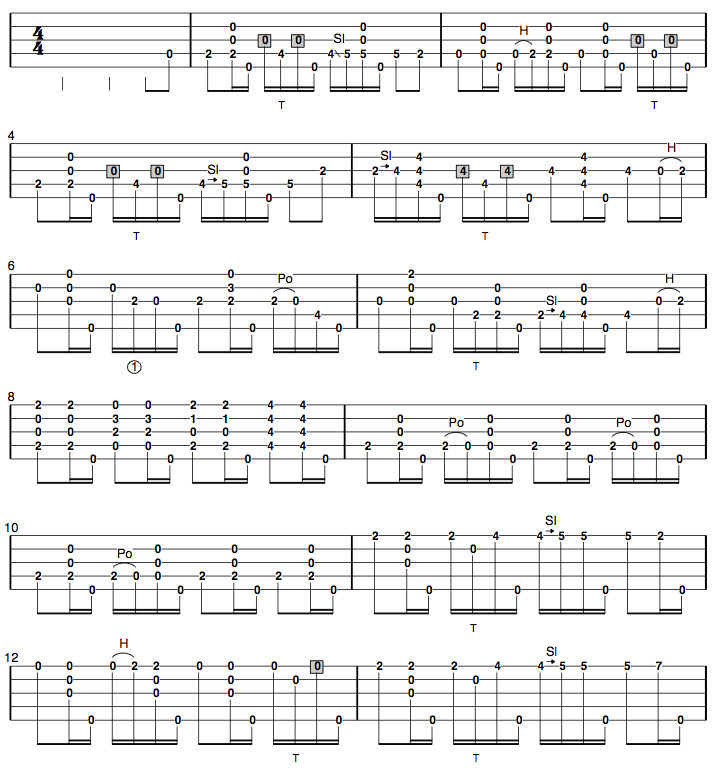

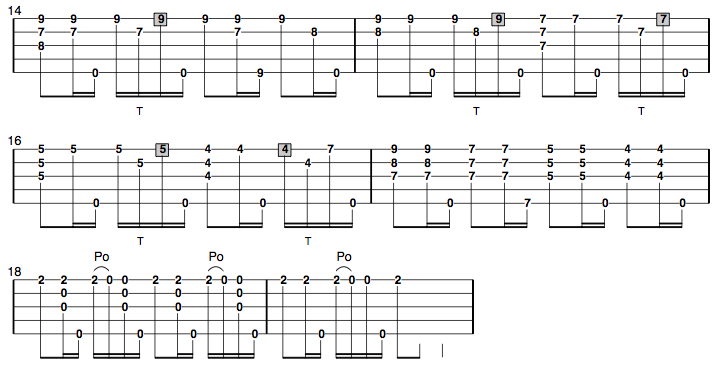

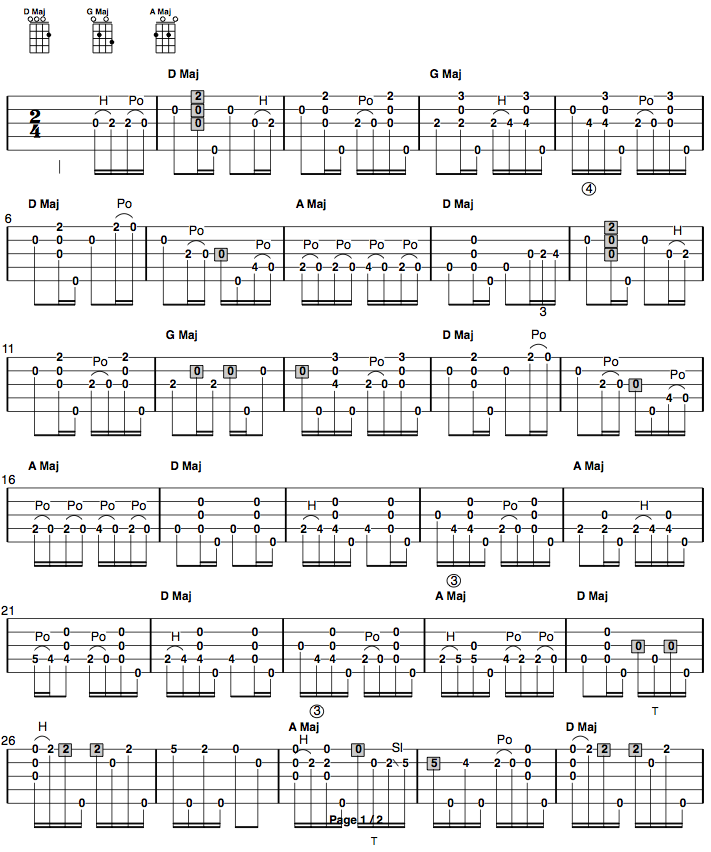

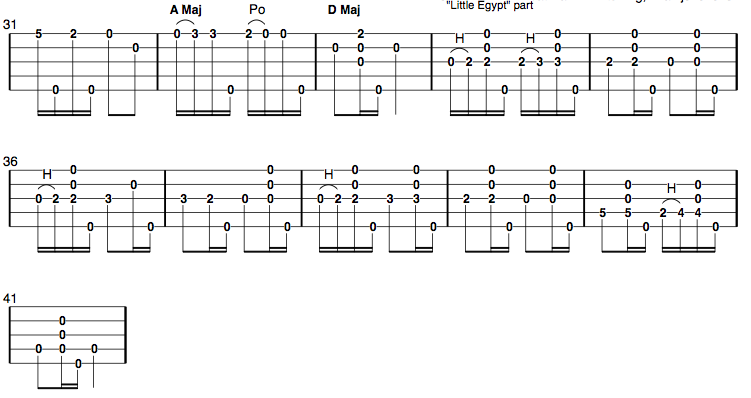

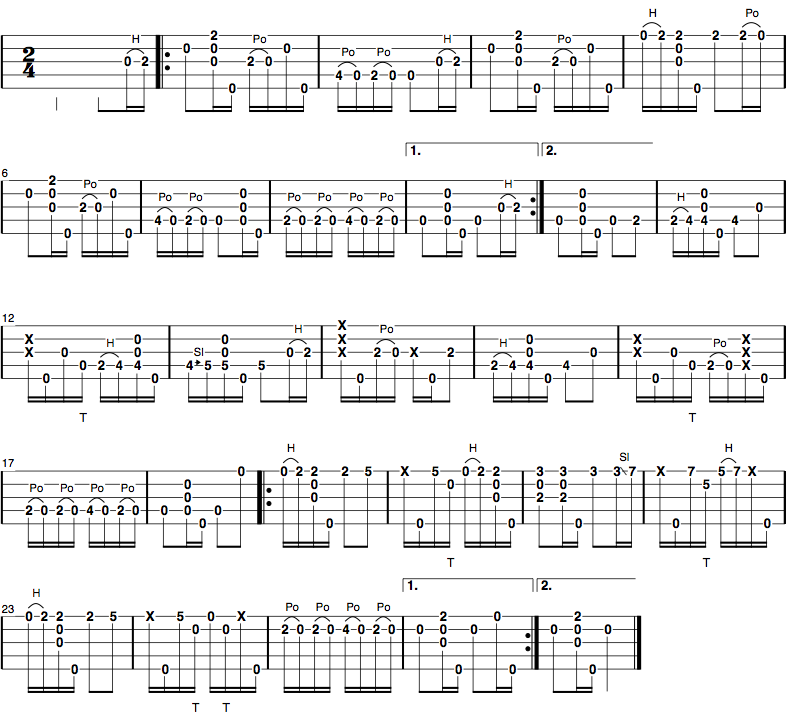

gDGBD tuning, Brainjo level 3

Notes on the tab

Skip Notes: The notes denoted as a shaded box are “skip” notes, meaning they’re not actually sounded by the picking finger. Instead, you continue the clawhammer motion with your picking hand, but “skip” playing the note by not striking it (this is a technique used to add space and syncopation). The fret number you see in the shaded box is the suggested note to play should you elect to strike the string.

Also, listen to the recording to here how I’ve adapted the original rhythm (played in the intro) to work as a 4/4 clawhammer piece.