I’m a great big fan of syncopation in music. It’s a major part of traditional American music, including Appalachian old-time, and I love adding it into my playing.

One of my favorite techniques for adding syncopation utilizes “skip notes”, usually in combination with a dropped thumb to create what I refer to as a “syncopated skip” note (you’ll see “skip” notes indicated in my tabs by a shaded box or an “X”).

I cover syncopation in depth as part of the Breakthrough Banjo course, however, I’ve received so much interest in this technique from folks that I thought I’d make the video on “syncopated skips” available to everyone. So, without further ado, here’s the video:

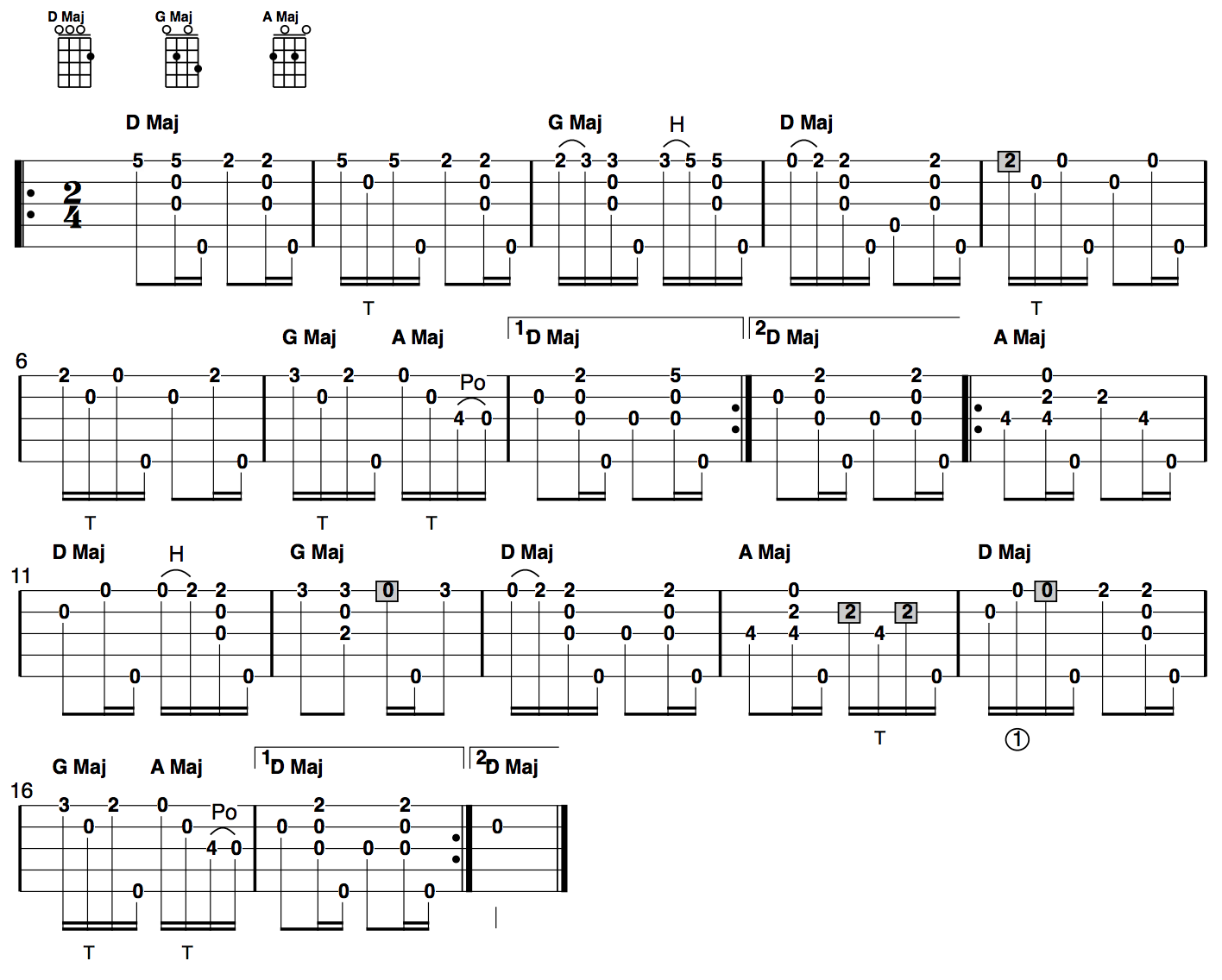

Syncopated Skips

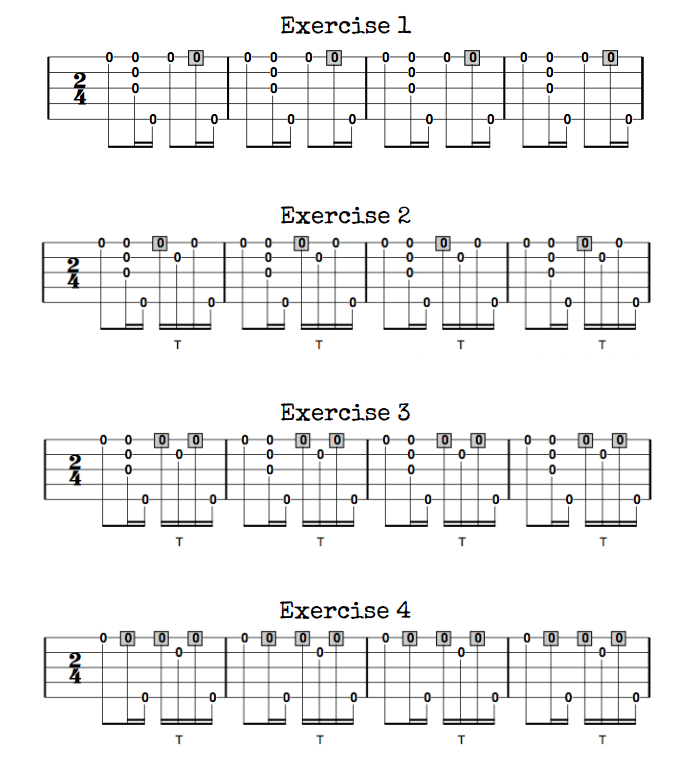

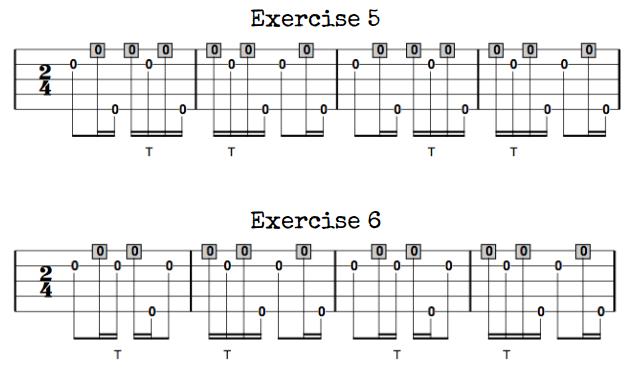

Picking Exercises from the Video

Syncopated Skip Exercises

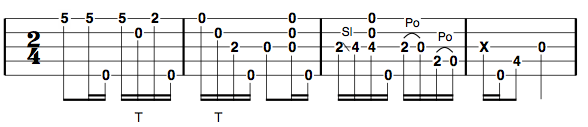

Step 3 – Add Some

Step 3 – Add Some  Step 4: Embellish to Taste

Step 4: Embellish to Taste